Mark Crislip is always a hard act to follow, particularly when he’s firing on all cylinders, as he was last Friday. Although I can sometimes match him (and, on rare occasions, even surpass him) for amusing snark, this time around I’m going to remain mostly serious because that’s what the subject matter requires. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I’m a bit of an odd bird in the world of cancer in that I’m both a surgeon and I run a lab. Sadly, there just aren’t very many surgeons doing basic and translational research these days, thanks to declining NIH funding, increasing clinical burden necessitated by declining reimbursements, and the increasing complexity of laboratory-based research. That’s not to say that there aren’t some surgeons out there doing excellent laboratory research, but sometimes I feel as though I’m part of an endangered species, particularly years like this when grants are running out and I need to renew my funding or secure new funding, the consequence of failure being the dissolution of my laboratory. It’s a tough world out there in biomedical research.

As tough as biomedical research is in cancer, to my mind far tougher is research trying to tease out the relationship between environmental exposures and cancer risk. If you want complicated, that’s complicated. For one thing, obtaining epidemiological data is incredibly labor- and cost-intensive, and rarely are the data clear cut. There’s always ambiguity, not to mention numerous confounding factors that conspire to exaggerate on the one hand or hide on the other hand correlations between environmental exposures and cancer. As a result, studies are often conflicting, and making sense of the morass of often contradictory studies can tax even the most skillful scientists and epidemiologists. Communicating the science and epidemiology linking environment and cancer to the public is even harder. What the lay person often sees is that one day a study is in the news telling him that X causes cancer and then a month later another study says that X doesn’t cause cancer. Is it any wonder that people are often confused over what is and is not dangerous? Add to this a distinct inability on the part of most people, even highly educated people, to weigh small risks against one another (an inability that has led to phenomena such as the anti-vaccine movement), and the task of trying to decide what is dangerous, what is not, how policy is formulated based on this science, and how to communicate the science and the policy derived from it to the public is truly Herculean.

The President’s Cancer Panel (PCP) marched straight into this fray last week by issuing its 2008-2009 Annual Report entitled Reducing Environmental Cancer Risk, What We Can Do Now. The Panel on Cancer was mandated under the National Cancer Act of 1971, the legislation passed as a result of President Richard Nixon’s declaration of “war on cancer,” and its function is to “monitor the development and execution of the activities of the National Cancer Program, and shall report directly to the President.” Previous reports have addressed subjects such as Promoting Healthy Lifestyles (2006-2007); Translating Research Into Cancer Care: Delivering on the Promise (2004-2005); Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance (2003-2004); and The Meaning of Race in Science–Considerations for Cancer Research (1997). Not surprisingly, this year’s report is more contentious than the average President’s Cancer Panel Report because few areas of cancer research are as controversial or impact as directly on public policy as the assessment of environmental risks of cancer and what to do about those risks.

The PCP report is very long (over 200 pages), although there is a lot of white space on each page, but for those of you who don’t feel inclined to read the whole thing, the executive summary does a good job of boiling down the vastness of the report into a more digestible chunk. It begins, as all such reports do, by pointing out the enormity of the cancer problem in the U.S.:

Despite overall decreases in incidence and mortality, cancer continues to shatter and steal the lives of Americans. Approximately 41 percent of Americans will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lives, and about 21 percent will die from cancer. The incidence of some cancers, including some most common among children, is increasing for unexplained reasons.

Public and governmental awareness of environmental influences on cancer risk and other health issues has increased substantially in recent years as scientific and health care communities, policy makers, and individuals strive to understand and ameliorate the causes and toll of human disease. A growing body of research documents myriad established and suspected environmental factors linked to genetic, immune, and endocrine dysfunction that can lead to cancer and other diseases.

Between September 2008 and January 2009, the President’s Cancer Panel (the Panel) convened four meetings to assess the state of environmental cancer research, policy, and programs addressing known and potential effects of environmental exposures on cancer. The Panel received testimony from 45 invited experts from academia, government, industry, the environmental and cancer advocacy communities, and the public.

In order to address the question of environmental influences on cancer, the Panel decided to address the following areas:

- Exposure to Contaminants from Industrial and Manufacturing Sources. These include a wide variety of manufactured chemicals and industrial by products used in the manufacture of mass-produced products. The report notes that numerous chemicals used in manufacturing remain on products as residues or are integral parts of the products themselves. It is also noted that new chemicals are being created continually.

- Exposure to Contaminants from Agricultural Sources. There are numerous chemical exposures due to chemicals used in agriculture, particularly pesticides, solvents, and fillers. Some of these leech into the soil and water and produce exposure this way.

- Environmental Exposures Related to Modern Lifestyles. These exposures include pollution from vehicles, chemicals used in pest control, and exposure to radio waves and electromagnetic fields from cell phone radiation and electrical power lines, respectively.

- Exposure to Hazards from Medical Sources. This source consists primarily of radiation from medical tests and the potential of contamination of the environment from discarded pharmaceuticals.

- Exposure to Contaminants and Other Hazards from Military Sources. There still remain a lot of areas around military bases. Nearly 900 Superfund sites are abandoned military facilities or facilities that produced materials for military use.

- Exposure to Environmental Hazards from Natural Sources. This class of exposure includes naturally occurring carcinogens such as radon, uranium, and arsenic.

Overall, the report is a comprehensive look at environmental exposures that could potentially contribute to various cancers and that we can do something about. In all my years in cancer research, I can’t recall ever seeing its like coming from such a mainstream source. The panel proposes several suggested approaches to this problem, including:

- The adoption of a new “precautionary, prevention-oriented approach” to replace our “current reactionary approaches in which human harm must be proven before action is taken to reduce or eliminate exposure.” As a part of this approach, it is recommended that the burden of proof of safety should be shifted to the manufacturer, rather than the current burden of proof being upon the government to prove harm.

- A thorough new assessment of workplace and other exposures to quantify risk.

- A more coordinated system for promulgating environmental contaminant policy and regulations driven by science and free of political and industry influence.

- Epidemiological and hazard assessment research in areas where the evidence is unclear.

- New research tools and endpoints to assess environmental exposure and risk, including high throughput models to assess multiple exposures simultaneously, methods for long term monitoring and quantification of electromagnetic energy sources, such as power lines and cell phones.

- Better policies regarding cancer risk due to radon.

- Actions to minimize exposure to medical radiation sources.

- Addressing the unequal burden to known and suspected carcinogens.

- Encouraging physicians to take better health histories of environmental exposures.

- “Green chemistry” initiatives.

- Measures to increase public awareness of risk due to environmental exposures.

As you can see, if the recommendations, some of the details of which are fleshed out (mostly) in the 200 page report, if adopted would require enormous policy changes. Of course, one thing that must be remembered about reports like this is that they are every bit as much political documents as they are scientific and medical documents. After all, they point out problems that very well could require new laws and/or new regulations in order to address. This report definitely falls into this category in a big way because, if adopted, its recommendations would demand action by the government. Indeed, the report itself blames weak laws, lax enforcement, and overlapping and conflicting regulatory authority, but, more strongly, it blames the attitude that industrial chemicals are safe unless strong evidence that they are not safe emerges.

But how strong is the science?

From my perspective, the report is a mixed bag, a mixture of the (mostly) good, a (little) bad, and (at least one) ugly thing. It’s also rather annoying that, of the over 400 references, most of them appear to be government reports and review articles, with very little primary literature cited. First the good, though. The report emphasizes quite strongly that what we know about the environmental contribution to cancer has lagged far behind our knowledge of other aspects of cancer. More importantly, one aspect of the environmental contribution to cancer that we often don’t consider strongly enough is that children tend to be more susceptible to environmental insults of many kinds, particularly carcinogenic insults:

An analysis by the National Academy of Sciences found that children are particularly vulnerable to environmental contaminants for several reasons. Due to their smaller size, children’s exposures to toxics are disproportionately large compared with adults. Because their metabolic pathways are immature (particularly during fetal development and in the first months after birth), they are slower to metabolize, detoxify, and excrete many environmental chemicals. As a result, toxins remain active in their bodies for a longer period of time than would be the case in adults. In addition, children have lower levels of some chemical-binding proteins, allowing more of a toxic agent to reach various organs, and their blood-brain barrier is more porous than that of adults, allowing greater chemical exposures to the developing brain. Children’s bodies also are less able to repair damage due to toxic exposures, and the complex processes that take place during the rapid growth and development of children’s nervous, respiratory, immune, reproductive, and other organ systems are easily disrupted.

Children have many more years of life ahead of them than do adults—more time in which to be exposed to environmental toxics and time to develop diseases (including cancer) with long latency periods initiated by early exposures.

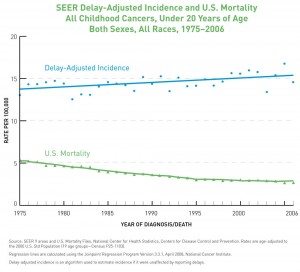

Moreover, at the same time that mortality rates for childhood cancers have been plummeting dramatically, the incidence of childhood cancers has been steadily climbing, as shown by this graph “borrowed” from the report:

The reason for this increase is not known, but genetics is an unlikely cause for such a rapid increase. In addition, it is unlikely that better diagnosis due to the introduction of MRI and better CT scanning is likely to be the cause, because the increase is too steady. That leaves environmental factors as one suspect for a major cause. Certainly, this is worth examining, as it may provide the “greatest bang for the buck.” Such studies could even benefit adults in terms of cancer risk. For example, lately, our cancer institute has become very interested in environmental contributors to breast cancer. One thing that has become clear is that such exposures may have their greatest effect in childhood or, in particular, during puberty, which is when the mammary gland undergoes its most rapid growth and development. Indeed, although this increases susceptibility to carcinogens in children has long been appreciated, but the characterization of these differences, again, has lagged behind other areas of cancer research. This is especially relevant to the section on the risk of medical radiation, with recent studies suggesting the possibility of tens of thousands of excess cancers in the U.S. due to medical radiation from the increasingly common use of CT scans and studies suggesting that radiation from mammography may contribute to a small number of breast cancers.

Another good part of the report is its emphasis on the deficiencies in our current technology and tools for assessing the carcinogenic potential of various chemicals. Related to the report’s emphasis on how little we know about carcinogenesis in children, the report criticizes current animal models because they fail to capture the impacts of early exposures and miss the late effects of such exposures. Also problematic is that most animal studies use long-term, high-dose exposures that may have little relation to humans. Consequently, the report urges the development of alternatives to animal testing involving testing in human cells in vitro. I’m rather skeptical that this recommendation will produce much benefit very fast. After all, one reason we use animals is because, as imperfect as animal carcinogenesis studies are, the correlation between cell culture studies is even more unreliable than that of animal studies.

One recommendation of the report that intrigued me was its assessment of how science has generally focused on one compound at a time without considering how they may interact. This reminds me of how in the past we concentrated on one gene at a time as a causative agent for cancer (such as oncogenes); yet over the past ten years it has become increasingly clear that cancer is often driven by many genes, each of which individually plays a relatively small role. The Panel thus recommends the development of high throughput screens that can examine many chemicals at once and test for interactions, a recommendation that struck me as worthwhile, although I am having trouble envisioning what such a test would look like or how it would be validated. The problem, of course, is that, as more chemicals are tested, the possible combinations skyrocket exponentially.

One major part of the report deals with one specific environmental exposure, the thousand pound gorilla these days, namely BPA, which was discussed in the context of the report’s increasing emphasis on the precautionary principle. This part of the report, to me, was a little bit dicey in that the precautionary principle is very difficult to apply. I’ve discussed this matter before in the context of how preemptively removing mercury from vaccines helped fuel an anti-vaccine panic over the mercury in the thimerosal preservative that used to be in vaccines. The question of how much evidence is necessary to justify banning a compound doesn’t go away, and it still remains a profoundly political question. The report basically glosses over the question of where one should draw the line in implementing the principle, other than suggesting shifting it to more caution. It also dances around the question of how we would pay for this, given that the implementation of the recommendations in this report would require massive increases in the budgets of the relevant agencies — particularly since the report itself documents just how short-staffed and under-funded many of these agencies are.

One glaringly dubious part of the report compared to the rest is how it deals with the issue of cell phones and cancer. After emphasizing that there is no good evidence to support a link between cell phones and cancer and pointing out that the epidemiological evidence is in essence negative, the report proceeds as though a link between cell phone use and brain or head and neck tumors were biologically plausible. As I’ve described before, it’s not. Indeed, from a biological standpoint, a strong link between cell phone use and brain cancer (or any other cancer) is not very plausible at all; in fact, it’s highly implausible. Cell phones do not emit ionizing radiation; they emit electromagnetic radiation in the microwave spectrum whose energy is far too low to cause the DNA damage that leads to mutations that lead to cancer. While it is possible that perhaps heating effects might contribute somehow to cancer, most cell phones, at least ones manufactured in the last decade or so, are low power radio transmitters. It is also necessary to acknowledge the possibility that there might be an as yet undiscovered biological mechanism by which low power radio waves can cause cancer, perhaps epigenetic or other, but the evidence there is very weak to nonexistent as well. Basically, based on what we know about carcinogenesis, a postulated link between cell phones and cancer is highly implausible. It’s not homeopathy-level implausible, but it’s pretty implausible nonetheless. Consequently, in the absence of better basic science, I have a hard time managing to muster any enthusiasm about recommending more studies than the ones that are already going on.

That ugly bit aside, though, the President’s Cancer Panel report is in general cautious and makes sensible policy recommendations. It also makes a number of (mostly) sensible recommendations for individual citizens. In general, it is cautious and highlights a neglected aspect of cancer research.

That must be why the pro-industry group American Council on Science and Health (ACSH) is on the counterattack, for example:

Elizabeth M. Whelan, president of the American Council on Science and Health, whose views often coincide with industry’s, noted that despite the growing exposure to chemicals in the environment, “cancer death rates are going down. The so-called environmental trace levels of chemicals play no role whatsoever in the etiology of cancer.”

And:

“This so-called Presidential Cancer Panel, which consists of two physicians, has obviously been politically pressured by the activists running the EPA,” says ACSH’s Dr. Gilbert Ross. “When they mention babies being ‘pre-polluted’ and the alleged dangers of all of these chemicals, they not only sign their name to activist screeds, they neglect to mention that the dose makes the poison, and that finding traces of chemicals at levels of parts-per-billion does not imply a health hazard. And of course they do not address the potential health hazards of banning important chemicals from consumer products.”

Of course, the obvious retort to that is that the presence of chemicals at levels of parts-per-billion doesn’t imply that there’s isn’t problem, either, but that’s apparently what ACSH wants you to believe. There may be a problem; there may not. We’ll never know if we don’t study the issue. It is probably true that most trace contaminants are not health hazards, it’s also very likely true that some of them are, and if we don’t study the issue we will never know. But that’s ACSH’s M.O.: deny there is a problem; deny even the possibility that there might be a problem; criticize the tools used to study a problem even if they are the best we have, however imperfect. Sometimes ACSH even takes it to ridiculous extremes. In other words, other than tobacco, when it comes to the assessment of health risks to listen to ACSH is in essence to hear industry’s viewpoint, as Jon Stewart demonstrated so brilliantly last year. Any organization that can claim with a straight face that encouraging healthy eating is “elitist” is not one that I can take seriously.

A more reasonable criticism comes from the American Cancer Society’s Michael J. Thun, MD:

Issues highlighted in both reports include the accumulation of certain synthetic chemicals in humans and in the food chain; the large number of industrial chemicals that have not been adequately tested; the potentially greater susceptibility of children; the possibility that some chemicals or combinations of chemicals may have effects at low doses; and the potential risks from widely used medical imaging procedures that involve ionizing radiation.

Unfortunately, the perspective of the report is unbalanced by its implication that pollution is the major cause of cancer, and by its dismissal of cancer prevention efforts aimed at the major known causes of cancer (tobacco, obesity, alcohol, infections, hormones, sunlight) as “focused narrowly.”

This seems to be missing the point by more than a bit. The very point of the report was to focus on an aspect of cancer prevention that the Panel considered to have been historically underrepresented. This year, the President’s Cancer Panel report was designed to focus on one aspect of cancer, namely environmental influences on cancer. As such, of course it emphasized — shockingly — environmental influences on cancer. It’s also just plain wrong that the report “dismisses” cancer prevention efforts aimed at the stronger known exposures and risk factors for cancer; rather, it argues that we should be doing more to ameliorate cancer risk from environmental exposures, be it to chemicals or the excessive use of medical radiation in imaging tests.

Basically, I found the ACS’s objections to be rather puzzling, given that just last fall the ACS published a position paper, many parts of which sound eerily similar to the President’s Cancer Panel report. For example, these are the things that the ACS recommends:

The position statement on cancer prevention also says:

- New strategies for toxicity testing, including the assessment of carcinogenicity, should be implemented that will more effectively and efficiently screen the large number of chemicals to which people are exposed. This very same recommendation is in the President’s Cancer Panel report.

- Occupational and community exposures should meet regulatory standards, and research to identify and reduce carcinogenic hazards should be supported. Ditto.

- The agencies that set and enforce environmental standards need to be appropriately funded and science-based to keep pace with scientific developments and to update their standards accordingly. This is more or less the same as what the President’s Cancer Panel recommends.

- Although certain exposures are unavoidable, exposure to carcinogens should be minimized or eliminated whenever feasible. A little different emphasis, but basically the same idea as embodied in the President’s Cancer Panel report.

- The public should be provided with information so that they can make informed choices. Absolutely the same as the President’s Cancer Panel report.

- Communications should acknowledge and not trivialize public concerns, but at the same time should not exaggerate the potential magnitude or level of certainty of the potential risk.

The last point seems to be the only point where the ACS and the President’s Cancer Panel differ significantly, and I will admit that the President’s Cancer Panel report is a bit too certain in its tone when it comes to several issues. And, straight from the article:

The exposure levels to the general public are typically orders of magnitude lower than those experienced historically in occupational or other settings in which cancer risks have been demonstrated. The resulting cancer risks are generally so low that they cannot be measured directly. Nevertheless, there is reason to be concerned about low-level exposures to carcinogenic pollutants because of the multiplicity of substances, the involuntary nature of many exposures, and the potential that even low-level exposures contribute to the cancer burden when large numbers of people are exposed. Concerns about the toxic and carcinogenic potential of these exposures are amplified by broader public concerns regarding the effectiveness of hazard identification and the regulation of potentially toxic exposures in the United States and other economically developed countries, as well as high levels of exposures to known carcinogens that still occur in many developing countries.

All of this is very similar to what is in the President’s Cancer Panel report, the main difference being more of emphasis than anything else and a disagreement over whether environmental contributions to cancer other than the strong, well-characterized ones (like smoking) are underestimated or not. At the risk of falling prey to the fallacy of the Golden Mean, I rather suspect that the real risk is somewhere in between the position of the ACS and that of the President’s Cancer Council. The reason that I don’t think the Golden Mean fallacy will be a big deal here is because the positions of the two are actually pretty close, despite Dr. Thun’s objections. When the ACSH points to the ACS as “harshly criticizing” the report, even going so far as to entitle one post Praise be to Thun, it’s clearly exaggerating the extent of disagreement for its own purposes.

The President’s Cancer Panel report represents a document that is at the same time scientific, medical, and also highly political, and that needs to be remembered. It has also been heartening to epidemiologists and public health officials, some of whom have criticized the National Cancer Institute system for publicizing avoidable causes of cancer other than smoking to be “virtually non-existent.” This report, as flawed as parts of it are, represents a refreshing first step towards addressing that shortcoming. My only fear is that, if the results are not communicated well, we could have a series of environmental cancer scares on the basis of very little evidence, given the uncertainty inherent in many of these studies. However, if this is handled well, the result could be science-based health policies that minimize public exposure to known carcinogens and give people the information necessary to allow them to act for their own benefit.