Gout feels like this

You or someone you know may have experienced gout before. It’s excruciatingly painful, debilitating, and not an event that anyone wants to repeat. Diet and alcohol consumption are regularly cited as causes of gout, and it’s widely believed that gout is a something you bring upon yourself, usually as a result of an indulgent lifestyle. This belief has been around for centuries – as long as gout has been documented. Gout used to be a status symbol – only those with enough wealth (and food) might be lucky enough to have a gout attack.

But what effect does diet really have on gout? While specific foods are undoubtedly aggravating factors, it’s also been known for some time that there is a genetic component to gout. However, the relative contribution of genetics vs. dietary choices is not as well understood. A new paper suggests that the impact of dietary choices on the causes of gout may be small, and that your genetics, not your diet, may be the primary factor influencing your risk of gout. So if you’ve had a gout attack, must you change your diet permanently? That’s the question that this new paper attempts to answer.

What is gout?

Gout is a consequence of excessive uric acid in the blood. Uric acid is produced by the body as a part of metabolism, and it is normally eliminated in the urine. Uric acid is only poorly soluble in blood, and when it crystallizes out of the blood (as urate) and into joints or the skin, it causes the condition known as gout. The big toe is affected in about half of cases, and it appears like a sudden case of inflammatory arthritis, causing swelling and pain.

Treating gout, once you have it, focuses on reducing pain and inflammation. Gout attacks will eventually go away on its own, but medication will reduce pain and hasten resolution. The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used, as are steroids, and colchicine, whose natural source (autumn crocus) was used to treat inflammation and swelling as far back as 1500 BCE. Most people need to treat a gout attack for about a week before symptoms resolve.

There are several factors that are associated with gout. Sex (males more than females), increasing age, race/ethnicity, and genetics – which we’ll come back to.

Once you’ve had one gout attack, you’re at risk of another. The focus then shifts to prevention. Lowering the blood level of uric acid is the goal, and that can be accomplished primarily through medication (a topic for another post) and lifestyle changes, which shift the balance of uric acid production (via the liver) and uric acid elimination (via the kidneys). Weight loss in the obese reduces uric acid levels. Medications can lower uric acid levels, which may be part of a long-term strategy to reduce urate deposits in the body. The other major intervention tends to be dietary changes, with the focus on reducing the consumption of foods that increase uric acid levels.

The relationship between diet and gout risk has been implicated for centuries. Through anecdotal observation, consumption of red meat, shellfish, alcohol, sugary beverages, and alcohol have been linked to a raised risk of gout. Dietary interventions, like the DASH diet and the Mediterranean diet have conversely been linked to reduced uric acid levels.

Despite dietary interventions and weight optimization, some people remain more at risk of gout, because of non-modifiable risk factors. This brings us to this new paper, which examines the relative contribution of diet and genetics to uric acid levels in a healthy population.

The latest study

This new paper is entitled “Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: meta-analysis of population based cohorts“, was published in The BMJ, and is from Tanya J Major and colleagues. It was a meta-analysis, or a study of studies, of five different studies. The objective was to examine the relationship between diet and serum urate levels, evaluating the relative contributions of diet and genetics to serum urate. In total the researchers had data on over 16,000 individuals (mainly of European ancestry) who did not have gout and were not taking drugs that would affect uric acid levels. Participants had uric acid levels measured along with dietary data and other demographic factors that might affect gout risk. Genetic risk factors were also identified. The primary measure was average serum urate levels and the variance in serum urate levels.

Diet and urate levels

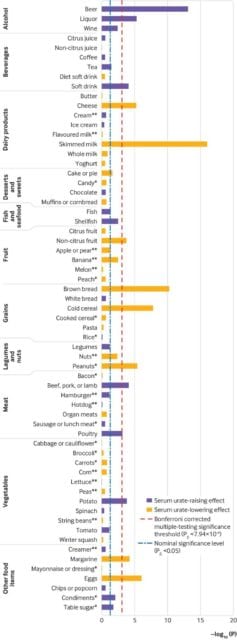

Fifteen foods were found to be significantly associated with serum urate levels in the total, male, or female cohort.

Increased serum urate levels

- Beer

- Liquor

- Wine

- Potatoes

- Poultry

- Soft Drinks

- Meat (beef, pork, lamb)

Decreased serum urate levels

- Eggs

- Peanuts

- Cold cereal

- Skim milk

- Cheese

- Brown bread

- Margarine

- Non-citrus fruit

The paper breaks down the differences between the males, females, and the full cohort, as well as the association with different diet scores. Here is the full table, which you’ll need to enlarge to view.

What’s remarkable is how modest the dietary effects are on serum urate levels, individually and in total:

Individually, the 14 food items associating with serum urate in the full cohort explained 0.06% to 0.99% of the variation in serum urate levels, and summed they explained 3.28% of the variation (table 1). All 63 food items, when summed, explained 4.29% of variation in serum urate levels (supplementary materials, table S5). Food groups (fruit, vegetables, meat, and dairy products) explained between 0.16% and 0.52% of variation in serum urate levels (supplementary materials, table S5). Unadjusted by the genetic risk score, the DASH diet score explained more of the variation in serum urate levels in the full cohort (0.28%; table 2) than the Healthy Eating (0.15%), Mediterranean (0.06%), or data driven (0.16%) diet scores, but each diet score explained less variation in serum urate than the most strongly associated individual food items (table 1).

Emphasis added.

Genetics had a much larger effect, and when you consider genetics, the food effects themselves are smaller:

In contrast, 30 genetic variants previously associated with serum urate levels at a genome wide level of significance in Europeans additively explained 8.7% of the variance in serum urate levels in the full cohort (excluding the NHANES III study; supplementary materials, table S8). A weighted serum urate genetic risk score constructed from these 30 variants,14 unadjusted by any dietary score, explained 7.9% of the variance (table 2). When included in models with the dietary scores, the percentage variance explained did not substantially change in the full, male, and female cohorts (maximum difference of 0.04%; table 2). The percentage variance explained by the dietary scores after adjustment for the genetic risk score fluctuated from a −0.09% difference for the data driven diet pattern in the male cohort to a +0.13% difference in the Mediterranean diet score in the male cohort (table 2). Genome wide estimations of serum urate heritability explained 23.9% of variance in serum urate levels in the full cohort (excluding the NHANES III study). The heritability estimates were 23.8% in the male cohort and 40.3% in the female cohort. Only the DASH diet score showed any evidence for an interaction with the weighted genetic risk score, and only in the female cohort (P=0.04); for all other interactions the P value was ≥0.21 (supplementary materials, table S9).

Emphasis added.

An accompanying editorial to this paper notes that these findings replicate the results of previous studies, but also note that correlations identified between potatoes, peanuts and margarine are new, and require confirmation.

There are several limitations to this study. The biggest limitation is the problem with food frequency questionnaires which are notoriously unreliable, and which differed slightly between the different studies that made up the meta-analysis. Secondly, this was a study in healthy patients, not patients that have gout, so a closer examination in those with gout is essential. This was also a group of patients who were mainly of European ancestry, living in the United States, so how far these findings can be generalized is not clear. It’s also important to note that this study doesn’t look at the impact of modifying diet on the risk of gout attacks, or whether specific foods can trigger gout in predisposed individuals.

Genes over diet?

Individual food choices contribute no more than 1% of an effect on serum urate levels, and diets overall appear to have very little influence. Genetic factors, conversely, are strongly correlated with urate levels and overall are responsible for over 20% of the variation in urate levels. While this is not a study of patients with gout, or a comparison of dietary changes vs. medication management, it does give further weight to the need for medication to help manage uric acid levels. This study should also give some reassurance to patients and health providers that, like so many other medical conditions, “blaming the patient” for their circumstances is harmful and wrong.