The last couple of weeks, I feel as though I may have been slumming a bit. After all, comparatively speaking it’s not that difficult to take on claims that homeopathy benefits fibromyalgia or Oprah Winfrey promoting faith healing quackery. Don’t get me wrong. Taking on such topics is important (otherwise I wouldn’t do it). For one thing, some quackery is so harmful and egregiously anti-science that it needs to be discussed. For another thing, they serve as examples of how even the most obvious quackery can seem plausible. All it takes are the cognitive quirks to which all humans are prone plus a bit of ignorance about what constitutes good scientific evidence to support the efficacy of a given therapy for a given condition.

So let’s move on to something a little more challenging.

Of all the attacks on science-based medicine (SBM), one of the favorite attacks made by its opponents is the claim that SBM is dangerous, that it kills or harms far more people than it helps. An excellent example of this occurred when quackery promoter Joseph Mercola teamed up with fellow quackery promoter Gary Null to write a widely cited article entitled Death by Medicine. Using the famous Institute of Medicine article that estimated deaths from medical errors to be on the order of 50,000 to 100,000 per year, Mercola and Null wove a scary story meant to imply that conventional medicine does far more harm than good. Of course, as our very own Harriet Hall pointed out, they concentrated solely on the harm, which makes it difficult to determine whether the harms truly outweigh the benefits. As Peter Lipson puts it, such arguments are intentionally designed to take our fears and exaggerate them out of all perspective. The idea behind the fallacious arguments used by the likes of Mercola and Null is that, because “conventional” medicine has problems and needs to improve its safety record, the quackery they promote must be a viable alternative to SBM. Yes, that is basically what their arguments boil down to.

The fallacious manner in which advocates for quackery such as Joe Mercola, Mike Adams, and Gary Null use and abuse any shortcoming of SBM that they can find (and, when they can’t find any, make some up) notwithstanding, there is a problem in SBM. Indeed, over the last 10 years or so since the IOM report, reducing the toll due to medical errors has — finally — become an incredibly important issue in medicine. Indeed, I myself have become involved in a state-wide quality improvement initiative in breast cancer as our site’s project director. As a result, I’m being forced to learn more about the nitty-gritty of quality improvement than I had ever thought I would. Combine this with a study published just before the Thanksgiving holiday in the New England Journal of Medicine, and I’m learning that improving care is incredibly difficult. The issues involved are many and tend to involve systems rather than individuals, which is why the solutions often bump up against the individualistic culture to which physicians belong. Moreover, such efforts, like comparative effectiveness research (CER), tend to earn less prestige than scientific research because, like CER, quality improvement initiatives do not in general look for new information and scientific understanding but rather at how we apply what we already know.

Quality versus safety

Another thing that needs to be remembered is that there is a great deal of controversy over which outcomes should be measured as indicators of quality care, particularly now that third party payors are supporting “quality improvement” initiatives. However, if you look at what is being measured, more frequently they are far more measures of safety (or, more properly), lack of safety than measurements of quality. In other words, what is being measured with a view towards minimization are error rates: medication errors; wrong site surgery rates; failure to adhere to well-established science-based guidelines, such as perioperative antibiotics, adequate sterile technique, and the use of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in appropriate patients; and, in general, anything that puts patient safety at risk based on what we know already. We already know that these practices decrease complication rates. Administering appropriate perioperative antibiotics and not allowing the patient’s body temperature to fall too far during surgery, for example, both decrease postoperative infection rates, as has been documented extensively through numerous studies. Leaving urinary catheters in longer than they are absolutely necessary increases rates of urinary tract infections. Failing to get patients out of bed as soon as possible after routine abdominal surgery increases the rates of postoperative pneumonia and deep venous thromboses. And so it goes. Some of these result in outcomes that, if proper systemic measures are in place to prevent them, should be very, very close to zero:

The concept of never events sounds appealing. Certain things should never happen. There are some never events. The surgeon should never remove the wrong leg or take out the wrong kidney. They should never leave an instrument in your abdomen after surgery. Patients should never receive another patient’s medications.

Other outcomes besides these are coming to be defined as “never events,” outcomes such as catheter-associated infections or leaving surgical instruments or sponges behind in a patient’s abdomen. Indeed, Medicare is no longer paying for care associated with several of these so-called “never events.”

Quality, on the other hand, is a more difficult concept to define, as Dr. Robert Centor describes. I wouldn’t go so far as to call the definition of quality “nebulous,” as he does. To me, that characterization goes too far. Rather, I would simply describe quality as being an concept where there is a lot more disagreement over what, exactly, constitutes “quality” care. True, safe care is definitely part of quality. After all, how could anyone define unsafe care as being “high quality”? In other words, safety is a necessary but not sufficient requirement for medical care to be considered high quality. For example, Dr. Centor further elaborates:

I am happy to see safety rates reported, e.g. central line infection rates, PICC line clot rates and or infection rates. These differ greatly from performance measures like % of MI patients given beta blockers. True safety parameters are not influenced by patient factors. We should minimize line infections through system work. We should decrease urinary tract infection rates. My distinction is that we can impact the untoward consequences of the things we do TO patients. We can agree on these, and fixing these problems is JOB #1.

After that, defining quality gets more difficult. Does it mean following more global science-based guidelines, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network‘s (NCCN) or the American Cancer Society‘s guidelines for the care of various cancers. These are different from simple quality measures in that they represent treatment algorithms designed more to optimize the overall care of cancer rather than relatively simple practices designed to protect patient safety. For example, one of the NCCN’s treatment guidelines for breast cancer requires that radiation therapy be offered to women who have undergone breast-conserving therapy within a certain time frame and that women with certain types and sizes of tumor be offered adjuvant chemotherapy. For purposes of this post, I will be sticking with safety measurements for the most part, because such measures are much more concrete and less contentious.

Checklists: Simple but overlooked

One of the most important points about quality improvement initiatives is that in general they emphasize doing what SBM already tells us to be the best practices. Examples include practices as obvious as giving perioperative antibiotics at the right time before operations and for the right operations. (For example, “clean” operations generally don’t need perioperative antibiotics.) One way to look at this is to give the right drug for the right type of operation at the right time before the operation until the right time after the operation. For most operations requiring perioperative antibiotics, the correct time to give the dose is a sufficient length of time to achieve therapeutic blood levels before the incision is made. If you administer the antibiotics after the incision has been made, you might as well not give them at all; at that point they don’t work to decrease the rate of infection.

One area that has received a fair amount of attention lately is the issue of infections and sepsis due to indwelling central venous catheters. Central venous catheters are catheters inserted directly into one of the large veins that drain to the heart, such as the internal jugular or subclavian vein. There, they frequently remain for days, sometimes for weeks. Because they are foreign objects that penetrate the skin and sit in large veins for (sometimes) long periods of time, central venous catheters can be the nidus for infection, and catheter-associated sepsis has traditionally been a difficult problem. Over the years, various practices have been advocated for reducing the rate of line-associated sepsis, including changing the line every three days and various other practices. As Atul Gawande pointed out in a famous New York Times editorial three years ago, however, it turns out that the most effective method for reducing catheter-associated sepsis:

A year ago, researchers at Johns Hopkins University published the results of a program that instituted in nearly every intensive care unit in Michigan a simple five-step checklist designed to prevent certain hospital infections. It reminds doctors to make sure, for example, that before putting large intravenous lines into patients, they actually wash their hands and don a sterile gown and gloves.

The results were stunning. Within three months, the rate of bloodstream infections from these I.V. lines fell by two-thirds. The average I.C.U. cut its infection rate from 4 percent to zero. Over 18 months, the program saved more than 1,500 lives and nearly $200 million.

Amazing. Just making sure to do an operating room-style scrub and then donning sterile gowns and gloves has an amazing effect on infection rates. Who knew? Actually, we all did–or, at least we should have.The problem was that surgeons inserting these catheters weren’t doing what they should have been doing. The reasons for this were probably multiple: Lack of time, the “it’s the way I was trained” excuse, and an inflated sense of how well each doctors were doing sterile technique, for example. As I put it at the time when I read Dr. Gawande’s article and the associated study, this is remedial Infection Control 101 for dummies. (Actually, I used a different word than “dummies.”)

This is the sort of thing that is meant by “safety,” namely doing very simple things that SBM tells us that we should be doing anyway. (The original study can be found here, for those interested.)

Increasingly, medicine is taking a page from the airline industry and instituting these checklists. Another study in which a checklist appears to have had salutary effects on patient safety was published by Dr. Gawande last year in the NEJM. The checklist tested involved some fairly basic things. It was divided into three sections. The “sign-in” section had typical elements, such as verifying patient identity; making sure that surgical site is properly marked with a marking pen; making everyone aware of any patient allergies; checking the pulse oximeter; and determining if there is a risk of aspiration or significant blood loss. The preop “time out” involved such things as once again verifying the patient identity and surgical site; making sure that any preop antibiotics have been given less than 60 minutes prior to skin incision; confirming that all appropriate imaging results were available, correct, and show what they are reported to have shown; and reviewing anticipated critical events. Finally, the “sign out” phase involved the typical surgical necessity of making sure that the sponge and instrument counts were correct before waking the patient up; checking any specimens to make sure they were labeled correctly; and reviewing aloud concerns about any issues that might interfere with the recovery of the patient.

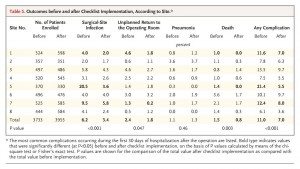

These measures were implemented at eight hospitals scattered throughout the world, both in developed countries and Third World countries. Sites included London, Seattle, Toronto, Tanzania, India, Jordan, the Philippines, and New Zealand. These hospitals had varying safety measures in place before the study, and none of them were as extensive as the checklist introduced as part of the study. The results are summarized in the following table (click to enlarge):

As you can see, the results were quite striking. But was it the introduction of checklists that resulted in this improvement? That’s difficult to say definitively from just this study. Certainly it is possible, but exactly how is harder to ascertain. One possibility is that the introduction of such checklists leads to a systemic improvement in how care is delivered driven by adherence to the principles embodied in the checklist. As the authors speculate in the discussion:

Whereas the evidence of improvement in surgical outcomes is substantial and robust, the exact mechanism of improvement is less clear and most likely multifactorial. Use of the checklist involved both changes in systems and changes in the behavior of individual surgical teams. To implement the checklist, all sites had to introduce a formal pause in care during surgery for preoperative team introductions and briefings and postoperative debriefings, team practices that have previously been shown to be associated with improved safety processes and attitudes and with a rate of complications and death reduced by as much as 80%. The philosophy of ensuring the correct identity of the patient and site through preoperative site marking, oral confirmation in the operating room, and other measures proved to be new to most of the study hospitals.

One interesting aspect of this initiative (interesting to me, at least) is the level of hostility to the results of the catheter study and this study that I encountered after they first came out. Doctors tend to resist checklists. I don’t know if this is anything unique to physicians, but given that airline pilots have used preflight checklists for years I’ve always had a hard time understanding the visceral reaction that such lists seem to cause in physicians. It’s as though too many of us consider ourselves so superior to our fellow human beings that the utility of such lists do not apply to us, we never forget to do anything, and never need reminding to do what we should be doing in the first place. To some extent, I can understand this reaction in that I used to make fun of what until about three years ago I used to disparage as the “mindless ritual” of my having to mark which breast I was going to operate on and to do a “time out” to verify it with the entire surgical staff in my operating room. I even used to say that once something is made into a rigid policy or checklist, it’s an excuse to stop thinking and mindlessly go through the motions. To some extent, I still think it’s important to guard against that tendency, but I’m far more supportive of checklists than I used to be.

In any case, the resistance of physicians to these sorts of checklists and various measurements that I mentioned at the beginning of this post appears to be due at least partially to the individualistic culture of physicians, but it should also be pointed out that malpractice concerns also appear to play a role. Indeed, sometimes this focus on the skills of the individual practitioner leads groups of physicians to resist even evidence-based medicine. In order to figure out how to prevent events that threaten patient safety, it is necessary to have a free and frank discussion of how such events occur, just as airlines do after crashes and near-misses.

But are checklists and safety measures having an effect?

While I’m sure most, if not all of us, can agree that this relatively newfound emphasis on improving patient safety and quality of care through guidelines, checklists, and other methods designed to ensure that, at the very least, the simple things that we know to be effective at improving patient outcomes are in fact being done, is long overdue, we still have to evaluate whether or not these measures actually work. In other words, are the rates of medical errors decreasing? Over the last couple of months, there have been two studies that are depressing in that they imply that the answer to that question might well be, “No.”

First, let’s take a look at one specific “never event,” namely wrong site or wrong patient surgeries. A recent study from the University of Colorado published in October in the Archives of Surgery, for example, found that wrong site surgeries, although rare, are more common than previous estimates, accounting for approximately 0.5% of all medical mistakes noted in the study. In a database of 27,370 physician self-reported adverse occurrences during a time period spanning January 1, 2002, to June 1, 2008, investigators identified 25 wrong patient and 107 wrong site surgeries. Significant harm was reportedly inflicted in 5 wrong-patient procedures (20.0%) and 38 wrong-site procedures (35.5%), and one patient died secondary to a wrong-site procedure (0.9%). Root cause analysis showed that most wrong-patient procedures were due to errors in diagnosis (56.0%) and errors in communication (100%), whereas wrong-site occurrences were related to errors in judgment (85.0%) and the lack of performing a “time-out” (72.0%). It should be pointed out that specialties were involved in the cause of wrong-patient procedures and contributed equally with surgical disciplines to adverse outcome related to wrong-site occurrences.

It should be also pointed out that there isn’t much in the way of convincing evidence that the Universal Protocol is currently helping.

Finally, as I mentioned above, right there in the New England Journal of Medicine last week was a study that specifically looked at trends over time for medical errors that caused patient injury. In brief, investigators at Harvard and Stanford Universities retrospectively examined the rate of medical errors at ten North Carolina hospitals from 2002 to 2007, chosen for this reason, as described in the introduction:

We chose North Carolina as a site that was likely to have improvement, since it had shown a high level of engagement in efforts to improve patient safety, including a 96% rate of hospital enrollment in a previous national improvement campaign, as compared with an average rate of 78% in other states, and extensive participation in statewide safety training programs and improvement collaboratives.

So what did these investigators find? Let’s just put it this way: This is one case where a picture is worth the proverbial thousand words:

This is Figure 2 from the study. As you can see, there is precious little, if any, improvement in the incidence of harm due to preventable medical errors, at least over the period studied from 2002 to 2007.

Where now?

One might conclude from the previous two studies that I presented that thus far all the safety/quality improvement modalities that have been implemented over the decade since the IOM report have been useless. However, although I do believe that boosters of checklists and various other safety improvement measures probably oversell their ability to make a dent in the rate of medical errors in American hospitals, I also don’t subscribe to the nihilistic view that none of this does any good. For one thing, it is very clear that in certain areas, carefully targeted checklists and other interventions can result in decreases in errors. However, medical errors span many specialties and many institutions, which means that, although, for example, central line checklists might very well greatly decrease the incidence of catheter-associated sepsis, such errors might represent a small enough percentage of overall medical error-associated harm that even huge decreases in such a complication don’t yet show up above the random noise and year-to-year fluctuations in the incidence of harm due to medical errors. Wrong-site surgeries, for instance, although catastrophic “never events,” are still, thankfully, rare; eliminating them, as important as that is, would not be expected to decrease overall rates of harm from medical errors by much. Unfortunately, we don’t appear even to be making much headway in this area.

Alternatively, one can argue, as the authors of these last two studies do, that we haven’t yet gone far enough in our safety interventions. For example, measures designed to prevent wrong site and wrong patient surgery are only implemented in the operating rooms:

But these protocols “are not sufficient,” Stahel says. They only apply to the operating room, he says, and nearly one-third of the botched procedures in the study took place in doctor’s offices. Moreover, the study showed that many operating-room mistakes start out in biopsy labs or during the imaging and diagnosis process.

“A lot of wrong-side, wrong-patient errors occur outside of the operating room,” Stahel says. “We should have time-outs for labeling for samples. If the lab mixes up the sample, the consequences may be worse than erroneously cutting off the wrong leg. I think we should extrapolate time-outs to internal medicine [and] laboratories.”

In the discussion of the NEJM study, the authors comment:

Our findings validate concern raised by patient-safety experts in the United States1 and Europe1 that harm resulting from medical care remains very common. Though disappointing, the absence of apparent improvement is not entirely surprising. Despite substantial resource allocation and efforts to draw attention to the patient-safety epidemic on the part of government agencies, health care regulators, and private organizations, the penetration of evidence-based safety practices has been quite modest. For example, only 1.5% of hospitals in the United States have implemented a comprehensive system of electronic medical records, and only 9.1% have even basic electronic record keeping in place; only 17% have computerized provider order entry.13 Physicians-in-training and nurses alike routinely work hours in excess of those proven to be safe. Compliance with even simple interventions such as hand washing is poor in many centers.

A reliable measurement strategy is required to determine whether efforts to enhance safety are resulting in overall improvements in care, either locally or more broadly. Most medical centers continue to depend on voluntary reporting to track institutional safety, despite repeated studies showing the inadequacy of such reporting. The patient-safety indicators of the AHRQ are susceptible to variations in coding practices, and many of the measures have limited sensitivity and specificity. Recent studies have shown that the trigger tool has very high specificity, high reliability, and higher sensitivity than other methods. Manual use of the trigger tool is labor-intensive, but as electronic medical records become more widespread, automating trigger detection could substantially decrease the time required to use this surveillance tool.

In other words, our ability to detect medical errors in retrospective studies is maddeningly inadequate, there is no standardization in how errors are reported or even mandatory reporting of such errors, and the efforts we have implemented have been largely confined to hospitals, when most patient receive care in the outpatient setting, including increasingly invasive procedures. Clearly, much more needs to be done. Checklists, such as the Universal Protocol, can only be part of the solution.

As disappointing as this is, I do find reason for optimism. Increasingly, regulatory agencies and third party payors are requiring the implementation of measures to improve patient safety. The problem is that, with the exception of some very obvious interventions, such as requiring hand-washing and sterile gowning before inserting central lines, some of these interventions have not been as well studied as they should be. For instance, it is widely claimed that the adoption of electronic medical records will allow for greater patient safety through the automation of checklists and various other safety checks. It is not yet clear that this will be true as EMRs are more widely adopted.

It should not be surprising that decreasing the rate of medical errors and the harm they cause does not lend itself to easy answers. The reasons for medical errors are many and multifarious, whether you accept the IOM’s estimates for the number of deaths caused by them or consider it flawed and likely an overestimate or an estimate without the context of what the expected death rate in hospitals would be in the absence of medical errors. Solving the problem and minimizing medical errors that result in harm will similarly not yield to a single strategy; our attacks on this problem will have to be as multi-pronged as the problem.