“Postnatal depression blood test breakthrough” proclaimed the headline. The UK Guardian article then declared:

British doctors reveal ‘extremely important’ research that could help tens of thousands of women at risk.

Here it comes. Readers were going to be fed a press release generated by the study’s authors and forwarded undigested by the media but disguised as writings of a journalist. If only the journo had asked someone in the know about the likelihood of a single study yielding such breakthrough blood test for risk of depression in new mothers.

The story echoed earlier churnalism from Sky News, British satellite television news service:

There is evidence that if you can identify women at risk early you could treat early or introduce measures to prevent or stop the process of the disease.

A study of 200 pregnant women, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, found two molecular “signatures” in the genes that increased the risk of postnatal depression by up to five times. One in seven new mothers suffer from depression.

Prof Grammatopoulos has claimed he could test women for the genetic changes for £30-£40, but the cost could be reduced to £10 if the screening system is automated.

By the time the story got to the Telegraph, it was embellished further:

Experts hope that the test will be available within two years, with results showing it to be at least 85 per cent accurate in early trials carried out by psychiatrists.

In the face of the considerable interest in the test being generated by the media coverage, the UK National Health Service (NHS) provided a critical evaluation from Bazian. The NHS coverage made good points but stopped short of blasting the media coverage and the author of the JPR article for their hype and hokum:

While the potential for inexpensive screening of postnatal depression is genuinely exciting, the limitations of the study – such as its size and the fact that it did not assess associations with diagnosed postnatal depression – should have been made more explicit by the papers.

Nothing in the existing literature prepares us for a study of 200 pregnant women yielding a clinic-ready £10 test for risk of postpartum depression. But further evaluation of these claims requires a detailed analysis of the original article in the context of the larger literature. The article is behind a pay wall, but if you cannot retrieve it from your university library, you can find an abstract here and request a copy from the senior author at d. grammatopoulos @ warwick.ac.uk.

A closer look

My examination confirmed the press coverage was nonsense and the article was not much better. There were far too few patients to identify genes associated with depression, and depression was not even measured. Any results would be unlikely to replicate. The authors went about it all wrong if their goal was make even a tiny step toward the distant goal of having a genetic test for depression. The conduct and reporting of the study was quite inconsistent with best practices for candidate gene studies. Finally, it is not clear how clinically useful and appropriate a blood test for risk of postpartum depression would be, which this decidedly is not, anyway.

Oh, but what a tale spun for the gullible. The press coverage and the article itself provide a good opportunity to hone the skills needed to detect hype and hokum. Especially, if you believe like I do that there is going to be a lot of it ahead with the search for biomarkers of depression having become such a hot topic.

- The study did not involve 200 women, only 140. The number 200 is the number of women approached, not the number of women enrolled.

- There was no diagnosis made of depression, neither while the women were pregnant nor after they had delivered.

- Instead, women were designated as “at risk” solely on the basis of their scores on a screening questionnaire, the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS). You can find it here. Although widely used, the scale is crudely constructed and psychometrically poor. It draws howls when women hit the item 6: “Things are getting on top of me”. “Damn, that’s how I got here…” a woman laughed out loud while being screened in my study of low income pregnant women in inner city Philadelphia.

- The EPDS yields a high rate of false positives when compared to a diagnostic interview. The investigators set a cutpoint of 10 for defining “at risk” rather than a more usual 13, which increases the yield of “at risk” women at the cost of sacrificing the positive predictive value of these designations.

- At the prenatal assessment 111 women had low scores, leaving only 29 “at risk.” The postnatal assessment revealed 34 patients scored high. Of these, only 21 were new high scorers. The other 13 represented 44% of the women scoring high at the prenatal assessment continue to do so. If we require that to be considered “postnatal depression,” the elevated scores could not have first occurred during pregnancy, we have to go with the lower number of 21 at risk.

A biological test with a claimed “accuracy of 85%” is being proposed as the basis for initiating treatment for pregnant women who are asymptomatic and not otherwise appropriate for treatment with antidepressants. And the “validation” of this biological test is not in a sample with a carefully diagnosed target condition. Rather, it is on the basis of responses of a few women to a screening questionnaire with items suggesting they are engaged in an exercise with all the scientific status of filling out a questionnaire that might be taken from a tabloid.

Yet somehow the press coverage made the startling claim that gene ‘signatures’ had been found carrying five times the risk of depression.

These small numbers mitigate not only against a valid genetic study, but even the use of suitable statistical controls. Note that the statistical power of a study to detect an effect is not a function of the overall sample size, but the size of the target group.

We can expect that such a grossly underpowered study:

- Will require larger effect sizes to attain statistical significance. If statistical significance is designated as the criterion for a discovery, any effect sizes will be inflated.

- Any use of statistical controls for potential confounds or to rule out alternative hypotheses is ridiculous and invalid.

- Reports of “discoveries” are likely to be false positives and to go unreplicated.

- Whatever is “discovered” is not about depression, because we do not have an adequate measure of depression.

We are at high risk of nonsense.

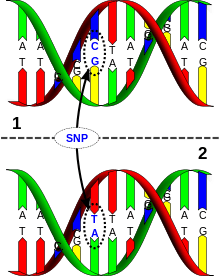

The investigators claim to have tested only five single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). We cannot know whether they actually tested hundreds, but are only reporting five. The rationale for testing only these five is weak, but let’s suspend skepticism for now. Still, the individual five SNPS were tested against three patterns of high risk and then combinations of SNPs were tested. And finally, haplotype distributions were globally and individually tested. Bottom line: the number of statistical tests approached the number of high risk women.

If you are still interested in the actually mixed results of this study, you can access the summary provided by the NHS here.

Authors as spin masters

Journalists at risk of becoming churnalists sometimes check a press release against the abstract of a journal article. Unfortunately, hyped press releases are associated with abstracts that spin the presentation and interpretation of results. To discover this, one usually needs to compare the abstract to the results actually reported in the text. But more basic spin can begin in the introduction, where the existing literature is given a biased summary in order to frame the importance of the research question that is being studied and the results that are obtained.

Abstract

The abstract opens with a stronger statement of the consistency of the existing literature that is justified. Only confirmatory findings from the study are presented, with null findings ignored. The abstract ends with an exaggerated declaration of this study being “the first evidence.”

Introductions

Introductions can be spun with a puffer fish strategy, exaggerating the prevalence and importance of a problem and with the creation of false authority by selective citation of the past literature. This introduction exhibits both.

The puffer fish strategy involves selectively citing and combining evidence so that the phenomenon under study is construed as highly prevalent with significant and long-lasting public health consequences. Authors thus puff up the importance of what they are studying by combining high estimates of prevalence with high estimates obtained from studies that actually tap different phenomena of the consequences of a condition going untreated.

In this case, high estimates of normally occurring postpartum blues (30-50%) are combined with studies of postpartum clinical depression (prevalence ~9%) which has more public health consequences, as well as the dangers associated with rare and entirely distinct phenomenon, postpartum psychosis (0.1 to 0.2%). The three distinct phenomena are treated as “depression,” establishing that the study is important because it is investigating a common condition having serious consequences for the mother and infant, including the possibility of maternal suicide and infanticide.

Selective citation creating false authority involves emphasizing positive studies and suppressing negative ones. But it also involves distorting what is cited so that the existing literature seems more uniformly consistent with the overall characterization of the literature, the framing of the research question, and the results that are obtained. Investigating the creation of false authority, one looks for missing null findings, citations for empirical claims that turn out to be not actually empirical studies, and citations of studies that upon examination turn out to have findings different than how they are cited or to be simply irrelevant.

There are lots of instances in this introduction, only a few of which I will cite.

Puzzlement is expressed that screening for postpartum depression is not universal, especially given the public health importance of it. What is ignored is a lack of evidence that routine screening would improve depression outcomes. There have also been large demonstrations that mandating implementation of screening for postpartum depression in specific settings such as the State of New Jersey Ob settings or Head Start programs, has not lead to women having lower depression scores.

The strong impression is created that postpartum depression is a distinctive condition, with an identified hormonal and perhaps genetic basis. The actual clinical epidemiological data suggest that women are no more likely to be clinically depressed immediately after giving birth than other comparably aged women who have not given birth. Much of the depression that is identified as postpartum actually began during pregnancy.

The introduction suggests that postnatal depression is likely to be associated with abnormalities in the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. That is a hypothesis with lots of contradictory data. One of the key problems is that postpartum depression is extremely heterogeneous. Depression identified by screening and interviewing, rather than from women seeking psychiatric services is likely to yield women in whom HPA axis abnormalities cannot be found.

Women identified on the basis of screening and interviewing will often meet criteria for major depression with the minimum number of symptoms and of only mildest severity. They are more likely to be suffering from personal and social difficulties than identifiable HPA axis abnormalities.

Think of it: are we really willing to assume that there has to be a genetically-based biological abnormality for a woman to endorse being sad, fatigued, lacking sleep, diminished concentration, and having recently lost 5% body weight in two weeks after giving birth?

The search for candidate genes for risk of depression involves tracking weak and inconsistent signals. These are likely to be lost in the static of including a considerable proportion of women lacking in distinct biological abnormalities.

The authors give particular attention to the hypothesis that postpartum depression is a result of increased production of placental corticotropin-releasing hormone (pCRH) during pregnancy that is abruptly withdrawn with the passing of the placenta during birth. This is another attractive hypothesis that has yielded lots of contradictory data. The bulk of the research has been conducted with small samples of women who have not assessed for clinical depression, but are designated “depressed” solely on the basis of a screening instrument.

The literature concerning pCRH and mood is also characterized by considerable confirmatory bias with negative findings either spun as positive in the original studies or selectively ignored and subsequent studies.

See, for instance, the study in the Archives of General Psychiatry that claimed finding “midpregnancy pCRH [placental CRH] is a sensitive and specific early diagnostic test for PPD symptoms” in a sample with 16 women identified by scores on the EPDS with more statistical tests than “depressed” women. And positive results emerged only with quadratic analyses, not linear ones. And only with statistical controls derived from an inappropriate automatic selection process. My group wrote the first author several times to get her to explain exactly how she claimed positive results. She did not reply.

The strength of evidence for genetic aspects of major depression is exaggerated. If you Google genetics and depression, the many links you will get will demonstrate wild fluctuations over time in declarations of breakthrough discoveries and disappointments, followed by more discoveries and disappointments. The consensus is now that single genes with great explanatory power are unlikely to be identified. Hope is now for small numbers of genes explaining small proportion of variance in distinctly different types of “depression.”

I could go on, but I think you can get the picture that the introduction misconstrues the existing literature as supporting this study as the next step. I could similarly analyze the discussion for the creation of a false consensus with the past literature. I was particularly impressed with the connecting of this study from a sample of Caucasian women to a study of Han Chinese patients not specifically selected for postpartum depression.

What are journos to do?

Journalists would garner a lot of attention if they were the first to report a true breakthrough study yielding an inexpensive blood test for risk of depression. But the overwhelming hype, false discoveries, and confirmatory bias in both the scientific literature and media coverage should caution against accepting claims by authors that single studies represent a breakthrough or that their claims will hold up in subsequent studies. As John Ioannidis has demonstrated, most claims of discoveries are either false or greatly exaggerated. In hot areas of research like this one, lower standards are set for declaring discoveries and so there are even more false discoveries and exaggerations that will not replicate.

Journalists cannot be expected to develop much expertise in biostatistics, clinical epidemiology, psychiatry or psychometrics. They cannot be expected to have the time or expertise to check for puffer fish strategies or the creation of false authority with selective citation.

But it is reasonable to expect that when authors approach them with press releases, journalists should maintain appropriate skepticism until they have checked out the press release with someone with relevant expertise, unconnected to the author.

Who else has responsibility to address misleading medical information being made available to consumer clinicians and patients? Are researchers only responsible for how their research is disseminated? Do others with relevant expertise have no responsibility to speak out?

As in a lot of areas of professionalism, an ethic of mutually avoiding critical commentary prevails: ‘Don’t criticize me and I won’t criticize you…Don’t call me on my hype and hokum and I won’t call you on yours.”

Special thanks to Marcus Munafo for encouragement and helpful feedback on earlier drafts and to Paul Ingraham for his editorial suggestions and from saving me from WordPress hell. However, all inaccuracies and excesses are the sole responsibility of James C. Coyne.