We here at SBM devote a lot of discussion to unscientific and pseudoscientific treatment modalities, the vast majority of which can be best described as quackery. Sometimes, though, what’s even more interesting are controversies in “conventional” science-based medicine. In particular, I’m a sucker for clinical trials that have the potential to upend what we think about a disease and how it’s treated, particularly when the results seem to go against what we understand about the pathophysiology of a disease.

So it was that I started seeing news reports last week about ORBITA (Objective Randomised Blinded Investigation With Optimal Medical Therapy of Angioplasty in Stable Angina). Basically, ORBITA is a double-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, or, as it’s more commonly referred to colloquially, coronary angioplasty and/or stenting) versus a placebo procedure in patients with coronary artery disease. Indeed, the sham procedure is what makes this trial interesting and compelling, although the devil is in the details. What this trial and its results say about coronary artery angioplasty and stenting, placebo effects, and clinical trial ethics are worth exploring. Basically, ORBITA calls into doubt the efficacy and usefulness of PCI in a large subset of patients with stable angina (chest pain or discomfort due to constriction of one or more coronary arteries that most often occurs with fairly predictably with activity or emotional stress—that is, exertion).

Before I dig in, I can’t resist mentioning that cardiac surgery was one of the very earliest forms of treatment in which the importance of a sham surgery control was shown to be very important. In 1939, an Italian surgeon named David Fieschi developed a technique in which he tied off (ligated) both internal mammary arteries through two small incisions, one on each side of the sternum. The idea was to “redirect” blood flow to the heart in order to overcome ischemic heart disease, in which the patient suffers pain, heart failure, or even death due to insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle caused by atherosclerotic narrowing of one or more of the coronary arteries. The results were striking, as three quarters of all patients on whom Dr. Fieschi did his procedure improved and as many as one third appeared to be cured. The procedure became very popular and appeared to work.

Nearly two decades later, in the late 1950s, the NIH funded a cardiologist in Seattle named Dr. Leonard Cobb to do a randomized controlled clinical trial of the Fieschi technique. He operated on 17 patients, of whom eight underwent the true Fieschi procedure, with both internal mammary arteries tied off, and nine underwent skin incisions in the appropriate location. In 1959, Dr. Cobb’s results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, where he reported that the results were the same for patients who underwent the “real” Fieschi operation or the sham procedure. This was the beginning of the end of internal mammary ligation as a treatment for angina and a landmark in the history of surgery. After this trial, understanding of the ethics of human subjects research changed, and including sham surgical procedures in clinical trial design became increasingly frowned upon.

ORBITA is one of several recent trials that use sham interventions that have been reported in recent years as that ethical understanding has shifted again in the face of increasing evidence that surgery can produce the most powerful placebo effects of all interventions. Another example is trials of vertebroplasty for vertebral fractures due to osteoporosis, which showed that vertebroplasty in this setting produced results indistinguishable from the sham procedure. Increasingly, it has been argued that more surgical trials should include a sham procedure group.

PCI: A brief history

Publication of the results of ORBITA were timed to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the development of PCI. Basically, coronary angioplasty was developed 40 years ago as a less invasive treatment than coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for coronary artery disease. In brief, in PCI a cardiologist will thread a catheter up a major blood vessel in the groin to the heart and into the coronary artery (or arteries) with blockages. At the end of the catheter is a balloon. The idea is to thread the end of the catheter under fluoroscopic guidance (fluoroscopy is a form of X-ray imaging with video) into the coronary artery and past the blockage, such that the balloon aligns with the atherosclerotic blockage. The balloon is then inflated to open up the blockage. That’s the basic idea, although the methods have evolved markedly over the last forty years.

At this point I can’t help but mention a bit of a personal note, as it involves the research I did as part of my PhD thesis, lo these many years ago. One of the huge problems with angioplasty early on was the high rate of restenosis (recurrent narrowing) of the blood vessel treated. The reason for this was that balloon angioplasty involved, in essence, injuring the vessel. As with any injury, there was an inflammatory reaction, and one consequence of the inflammatory reaction due to angioplasty is that the vascular smooth muscle cells in the media (the middle layer of the blood vessel) would be stimulated to proliferate and restenose the vessel. As part of my PhD thesis, I cloned and characterized a homeobox gene (yes, a homeobox gene, for you geeks out there) that inhibited the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. The idea was to treat the area at the time of the procedure with this gene as a form of gene therapy to prevent restenosis.

I realize that those of you out there who might be cardiologists and who weren’t practicing back in the 1990s probably think this was an insane idea, but here’s why it wasn’t so insane back then. In those days, coronary stents hadn’t been perfected, much less the drug-eluting coronary stents that are commonly used now to prevent restenosis. Basically, after most angioplasty procedures now, cardiologists place a stent in the area of former blockage. To prevent cellular ingrowth into the holes of the stent and subsequent restenosis, the stent slowly elutes a drug that prevents the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. (As an aside, one of the things about these stents that frequently causes problems to surgeons like me is that the patient needs to be on powerful anti-platelet drugs like Plavix for up to a year after stenting). In any case, with the development of drug-eluting stents, the idea of gene therapy to prevent restenosis disappeared into the dustbin of scientific history, for the most part.

Back when PCI was new and young, its indications were a lot more limited, but as time went on and cardiologists’ confidence grew indications expanded to multivessel disease and other indications that used to mandate CABG, to the point that PCI for acute coronary syndromes has grown to predominate. As MedPageToday describes:

In the early years of PCI it was widely believed that PCI to open a severely blocked artery would have long term cardiovascular benefits, even in stable patients. Angina patients, the thinking went, were at higher risk for CV events and death, and PCI or CABG lowered that risk by restoring flow through the blocked vessel and preventing a future MI. But doubts grew over time, as it became increasingly clear that MIs were more likely to occur at other, less obvious blockages. Coronary artery disease began to be seen more as a systemic condition and less as a focal plumbing problem. The positive role of medical therapy, including statins and aspirin, became increasingly recognized.

Finally, a decade ago the COURAGE trial, despite widespread and fierce initial resistance in the interventional cardiology community, led to widespread agreement that in fact PCI in stable lesions did not produce long-term improvements in outcome when compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT).

But PCI for stable angina maintained a strong clinical presence as a new consensus emerged in the cardiology community that PCI was superior to OMT in the relief of symptoms. The mantra was that patients would need a stent eventually so they might as well get it upfront. It is this reduction in symptoms that the ORBITA trial sought to test.

And it is this assumption or belief that ORBITA called into doubt, at least for one large subset of patients.

ORBITA

ORBIT has been published in the online first section of The Lancet; so let’s dig in. The introduction tells the tale, and you don’t even have to leave the abstract:

Symptomatic relief is the primary goal of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in stable angina and is commonly observed clinically. However, there is no evidence from blinded, placebo-controlled randomised trials to show its efficacy.

Or, in more detail in the introduction:

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was originally introduced to treat stable angina.1 More than 500 000 PCI procedures are done annually worldwide for stable angina. The Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial showed no difference in myocardial infarction and death rates between patients with stable coronary artery disease who underwent PCI and controls.2 Meta-analyses have shown similar results.3

Angina relief remains the primary reason for PCI in stable coronary artery disease.4 Guidelines recommend antianginal medication as rst line therapy, with PCI reserved for the many patients who remain symptomatic.5

Data from unblinded randomised trials have shown significant exercise time improvement, angina relief, and quality of life improvement from PCI.6–8 However, symptomatic responses are subjective and include both a true therapeutic effect and a placebo effect.9 Moreover, in an open trial, if patients randomised to no PCI have an expectation that PCI is advantageous, this might affect their reporting (and their physician’s interpretation) of symptoms, artifactually increasing the rate of unplanned revascularisation in the control group.4,10

So the investigators who designed ORBITA sought to do a rigorous randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial of PCI for patients in stable angina. One can argue that such a trial should have been done a long time ago, before PCI became such a popular procedure for stable angina, and you would be correct. However, it’s been done now; so let’s look at the design. First, the inclusion criteria:

- Age 18-85 years

- Stable angina/angina equivalent

- At least one angiographically significant lesion (≥70%) in a single vessel that was clinically appropriate for PCI

Exclusion criteria:

- Angiographic stenosis ≥50% in a nontarget vessel

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- Left main stem coronary disease

- Contraindications to DES

- Chronic total coronary occlusion

- Severe valvular disease

- Severe left ventricular systolic impairment

- Moderate-to-severe pulmonary hypertension

- Life expectancy <2 years

- Inability to give consent

Other features of the patient population studied:

- Previous PCI: 13%

- Left ventricular ejection fraction normal: 92%

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina severity grading class: I (3%), II (59%), III (39%)

- Angina duration: 9 months

- Vessel involved: left anterior descending (69%)

- Median area stenosis by quantitative coronary angiography: 85%

- Median baseline FFR value: 0.72; median post-PCI FFR value: 0.9

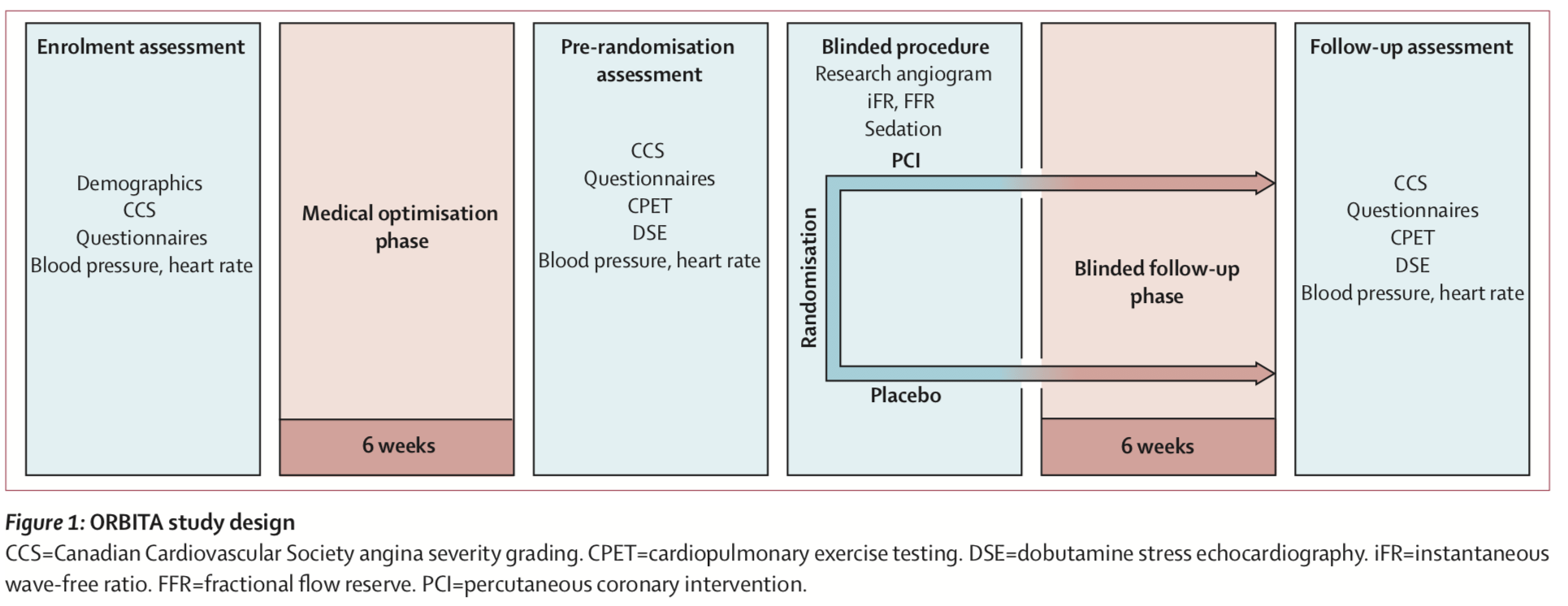

The primary endpoint to be assessed was improvement in exercise time. Patients with stable angina and evidence of severe single-vessel stenosis were randomized 1:1 to either PCI or a sham procedure. After enrollment, patients in both groups underwent six weeks of medical optimization. After that, they underwent either PCI or sham procedure with auditory isolation in which the subjects all wore headphones playing music throughout the procedure. During the procedure, patients’ heart function (measurements known as fractional flow reserve (FFR) and instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR)) was monitored using a research method, but operators were blinded to the physiology values and did not use them to guide treatment. Randomization occurred after this physiological assessment. For patients undergoing PCI, the operator used drug-eluting stents according to standard clinical guidelines with a mandate to achieve complete revascularization as determined by angiography. In the sham procedure group, subjects were kept sedated in the cath lab for at least 15 minutes, with the coronary catheters withdrawn with no intervention having been done. Here’s the summary of the timeline and allocation of the trial:

Here’s the trial outline:

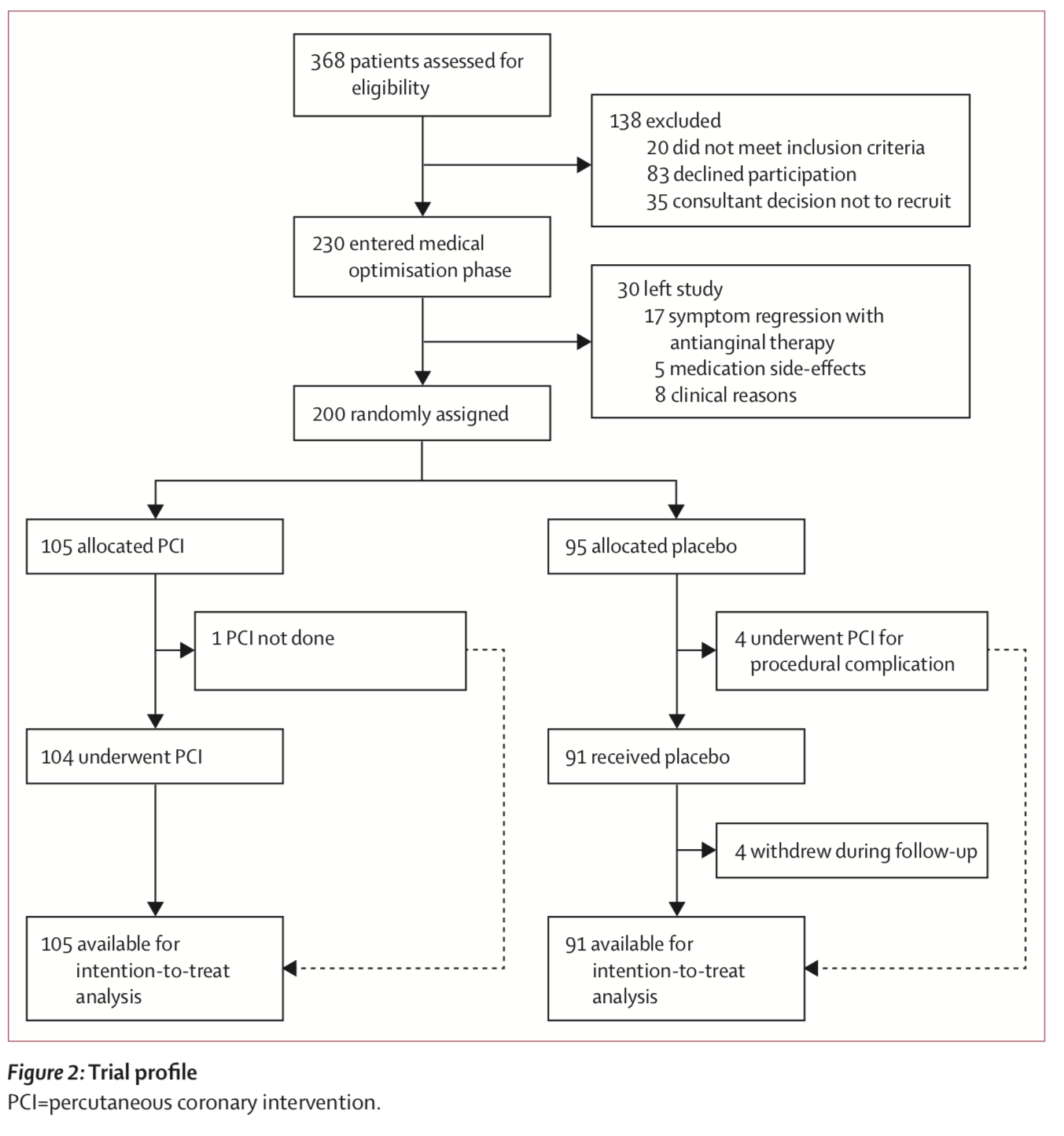

Overall, there were 230 patients enrolled, of which after the medical optimization phase 200 were randomized, with 105 patients assigned to PCI and 95 assigned to sham procedure. And the results? They were what we call in the business a big nothingburger. The change in exercise time from baseline for PCI vs. sham, was 28.4 vs. 11.8 seconds, p = 0.2. Secondary outcomes were no better:

- Change in Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ)-physical limitation from baseline: 7.4 vs. 5.0, p = 0.42

- Change in SAQ-angina frequency from baseline: 14.0 vs. 9.6, p = 0.26

- Change in Duke treadmill score from baseline: 1.22 vs. 0.1, p = 0.10

Also, at followup six weeks later, patients in both groups were receiving a mean of 2·9 medications; so PCI didn’t decrease the need for cardiac medications. In other words, there was no statistically significant change in either the primary or secondary outcomes in patients with stable angina. The authors noted:

In ORBITA, the first blinded, placebo-controlled trial of PCI for stable angina, PCI did not improve exercise time beyond the effect of the placebo. This was despite the patients having ischaemic symptoms, severe coronary stenosis both anatomically (84·4% area reduction) and haemodynamically (on-treatment FFR 0·69 and iFR 0·76), and objective relief of anatomical stenosis, invasive pressure, and non-invasive perfusion indices (FFR p<0·0001, iFR p<0·0001, stress wall motion score index p=0·0011). There was also no improvement beyond placebo in the other exercise and patient-centered effects with placebo effects. Forgetting this point, or denying it, causes overestimation of the physical effect.

In an accompanying editorial, David L. Brown and Rita F. Redberg commended the ORBITA investigators for “challenging the existing dogma around a procedure that has become routine, ingrained, and profitable,” noting that ORBITA shows “(once again) why regulatory agencies, the medical profession, and the public must demand high-quality studies before the approval and adoption of new therapies” and characterizing PCI for stable angina as putting “PCI in the category of other abandoned therapies for cardiovascular disease, including percutaneous trans-myocardial laser revascularisation10 and catheter-based radiofrequency renal artery sympathetic denervation11—procedures for which the initial apparent benefit was later shown in sham-controlled blinded studies to actually be due to the placebo effect.” Noting that the short duration of followup actually would favor PCI because “any haemodynamic benefit from PCI occurs early and the benefits of medical therapy continue to accrue over years,” Brown and Redberg conclude:

The implications of ORBITA are profound and far-reaching. First and foremost, the results of ORBITA show unequivocally that there are no benefits for PCI compared with medical therapy for stable angina, even when angina is refractory to medical therapy. Based on these data, all cardiology guidelines should be revised to downgrade the recommendation for PCI in patients with angina despite use of medical therapy. ORBITA highlights the importance of including sham controls and double blinding in a trial to avoid being fooled by illusory improvements due to the powerful placebo effect of procedures such as PCI. Although sham-control procedures are associated with some adverse outcomes, those complications are dwarfed in magnitude by the rate of adverse events in the approximately 500 000 patients who undergo PCI for symptomatic relief of stable angina in the USA and Europe each year. These adverse events include death (0·65%), myocardial infarction (15%), renal injury (13%), stroke (0·2%), and vascular complications (2–6%).12 Health-care providers should focus their attention on treating patients with stable coronary artery disease with optimal medical therapy, which is very effective, and on improving the lifestyle choices that represent a large proportion of modifiable cardiovascular risk, including heart-healthy diets, regular physical activity, and abstention from smoking.

Based on the results of this trial, one can easily argue that PCI should rarely—if ever—be performed in patients with single vessel disease and stable angina.

The backlash

Not surprisingly, there was pushback. Cardiologists were not pleased by this result, even though it has been well known for a long time that in patients like those studied in ORBITA, PCI at least doesn’t improve survival or decrease progression to need revascularization more than OMT. For instance, in a comment on the study various cardiologists were quick to make excuses:

Panelist Dr Martin Leon (Columbia University Medical Center, New York City) applauded the investigators efforts for a “remarkable study” but said it’s a much, much higher bar to achieve when the end points are differences from baseline between two groups.

“Baseline data demonstrating that these patients had very good functional capacity, had infrequent angina, had very little ischemia, means that regardless of what you did to the coronary artery there was going to be very little you could demonstrate in terms of clinical therapeutic benefit. So I’m really glad that PCI had a statistically significant benefit in both echos and the stress tests,” Leon said.

“The concern here is the results will be distorted and sensationalized to apply to other patient populations where this kind of outcome very likely would not occur,” he added.

My counter to the argument that the patients included in this trial were not that sick is: Yes! That’s the point. These are exactly the sorts of patients who too frequently are subjected to PCI for in essence no benefit over that which can be achieved by medical management.

Next up:

Commenting for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, Dr Roxana Mehran (Ichan [sic] School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City) said, “To me actually this study shows angioplasty is quite effective in reducing ischemia, improving [fractional flow reserve] FFR, and in fact I’m actually very pleased with this. It’s exactly what I want to do for my patients—improve their blood supply.”

Asked whether this isn’t just a positive spin on a negative study, Mehran quickly responded, “No,” adding that whenever a primary end point is a change in a value, showing an important difference is very hard to do when baseline values are so good, especially with only 200 patients.

“I promise you, had she studied 400 patients this would be positive because everything was in the right direction,” she said.

Actually, that’s exactly what she’s doing, trying to put a positive spin on a negative study. It’s so blatantly obvious that that’s what Dr. Mehran is doing that she should really be embarrassed to have said something like this to be published for the public to read. In fairness, she does have a germ of a point in that the study was relatively small and potentially underpowered to detect some differences. On the other hand, it’s rather interesting to note how some cardiologists totally twist the usual rationale and methodology used to determine if a therapy works. Here’s what I mean.

Normally, when a new intervention is first tested, it’s tested in small pilot trials. If a positive result is observed, that result justifies a larger trial to confirm efficacy and safety. If a positive result is not observed, then the treatment is generally abandoned or modified before being tested again. Now, get a load this:

During the press briefing Dr Robert Yeh (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA) congratulated the authors on a courageous, bold, and well-executed trial but said the results reaffirm in many ways those from COURAGE.

“To extrapolate that this means that elective PCI is not an indicated procedure is the furthest overreach that I can possibly imagine from a very small and I think hypothesis-generating trial with an interesting result,” he said.

Let’s grant Dr. Yeh his characterization of this study as “hypothesis-generating.” When hypothesis-generating studies are negative, the hypothesis is usually considered to be not worth testing further, barring serious methodologic or design issues in the hypothesis-generating study. To demand another, much larger, much more expensive study to follow up on a result that, even if Dr. Yeh is correct, would likely be a very modest difference in an increase in exercise tolerance. Basically, much, although in fairness not all, of what these cardiologists are doing is to make excuses.

None of this is to say that ORBITA is bulletproof. It is, compared to other trials of PCI, relatively small. There was a trend towards improved exercise tolerance in the PCI group compared to the sham group that might have been significant with more patients. The question, of course, is whether it would be worth it to do another larger trial. After all, interventional cardiologists are utterly convinced that PCI is more effective than OMT and are unlikely to change practice (much) based on this trial:

How will the results of ORBITA be viewed? It will be a combination of love and hate. ORBITA was rigorously designed and undertaken with great care and painstaking attention to detail using objective exercise and physiologic outcome measures before and after stabilization on OMT, combined with the use of well-validated quality of life metrics before and after randomization. Overall, the results were stunningly negative, which ORBITA supporters will cite. By contrast, it is very likely that many in the interventional community will be ready to pounce on and discredit this study — there certainly hasn’t been an opportunity since COURAGE was published 10 years ago in 2007 to potentially discredit a trial that now confronts the sacred cow of PCI benefit for angina relief as the sole basis to justify PCI in stable CAD patients. They will likely cite the limitations of small numbers (only 200 patients), that the study was woefully underpowered, the potential ethical conundrum of subjecting subjects with significant flow-limiting CAD to a sham procedure (or deferred PCI for clinical need), that 28%-32% of randomized subjects had either normal FFR or IFR (and therefore didn’t have a “physiologically significant,” or flow-limiting stenosis, that PCI would otherwise benefit), that there was a low frequency of multivessel CAD, that the short duration of follow-up (only 6 weeks) was too brief to assess potential benefit (though this actually favored the PCI group) and, of course, who would have the time or patience to call patients three times/week to assess their response to intensifying medical therapy — “not real-world,” just like the OMT used in COURAGE wasn’t achievable in the real-world.

Despite these reactions, I do have some optimism. Interventional radiologists reacted very negatively to the trials showing that vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures doesn’t work. Eventually, they started to come around, and usage of vertebroplasty for this indication is declining, albeit not as fast as it should. Science- and evidence-based medicine is messy, and there is some truth to the old adage that old treatments don’t ever quite disappear until the generation that learned them retires or dies off. But change does come in response to clinical trials.

In the meantime, whatever effect ORBITA has on clinical practice, it should serve as a wakeup call that in clinical trials of surgical or procedural interventions examining endpoints with a degree of subjectivity (unlike, for instance, death or time to cancer recurrence), whenever possible, new interventions should be compared to sham procedures. Of course, this isn’t always possible, either for ethical or practical reasons, but when it is practical sham procedures are just as essential as placebo controls in drug trials.