Today’s post isn’t about the flu vaccine, but that vaccine played a part in bringing you today’s topic. It seems that this year’s vaccine is a mediocre match for the circulating strains of influenza, and I was one of the unlucky ones in whom it didn’t appear to provide much protection. After spending several days effectively bedridden, I still feel like I’m emerging from a cognitive fog. So today’s post will be short. In the midst of my own infection, the results of a new study were announced that examined the effects of HPV vaccination on indicators of sexual behaviour in adolescent girls. I admit to being a bit dumbfounded by the topic when I heard it, and I initially thought I had heard the research question incorrectly. After all, the answer seemed (to me) so clearly self-evident, I questioned if this was an ineffective use of research dollars. This question seemed as pertinent as continuing to study the relationship between vaccines and autism: there is little reason to think there would be any causal relationship. But surveys of parents show this is a real concern for some. And now we have an answer grounded in real-world evidence.

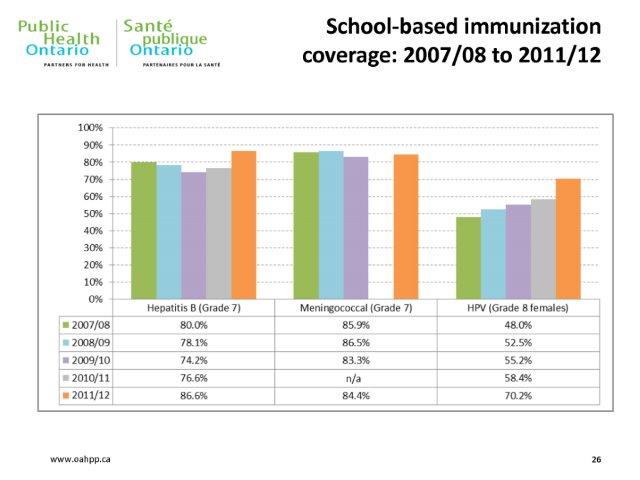

The HPV vaccine is an effective means of preventing cancer. Let’s pause to reflect on the sentence I just wrote. We can prevent cancer, before it starts, with a vaccine. The human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually-transmitted infection in North America, and almost all cervical cancer is caused by HPV. HPV causes a substantial number of cancer cases every year (26,000 per year in the US). As an anti-cancer strategy, vaccination is a pretty sensible one. HPV is not the only sexually-transmitted infection that can be prevented by vaccine. Hepatitis A and B are also sexually transmitted, and can be prevented with vaccines. However, immunization rates for HPV have lagged those of HBV and HAV, and anecdotally I haven’t seen a parental backlash against the hepatitis vaccines like I’ve seen against Gardasil and Cervarix, the two brands of HPV vaccine. Here are some uptake statistics for the Province of Ontario, where you can see the difference between hepatitis B and HPV:

I’m not going to spend time in this post reviewing the efficacy of the vaccine – that’s been blogged about before, and the CDC has excellent resources. And the safety of the vaccine has also been well established, in girls as well as boys. Despite what you may read on Natural News, Mercola or see in your Facebook feed, the HPV vaccine is effective and it lacks serious side effects. It is well tolerated and it works. Gardasil provides protection against four strains of the virus and Cervarix protects against the two strains that cause the most cases of cervical cancer.

The first vaccine, Gardasil was launched in 2006 and since that time has come to be offered by many public health agencies worldwide. In Ontario, where I happen to live, the program to vaccinate all girls started with the 2007 grade 8 cohort. The vaccine is offered in schools. Regrettably, the appropriateness of the vaccine was initially an issue with the publicly-funded Ontario Catholic School system but it’s now my understanding that the vaccine is being made routinely available to all grade 8 girls in Ontario. There are still substantial opt-out numbers, as you can see.

So why are HPV vaccination rates lagging? There’s been considerable study into the factors that influence vaccination decisions, and which can potentially be modified. You might expect that decisions are based on knowledge about the vaccine, but there doesn’t seem to be a relationship between the two. That is, some with low vaccination knowledge accept the vaccine, and some with a sophisticated knowledge base do not accept it. Studies of behaviours suggest that this factual knowledge about the vaccine may not make any material difference in decision-making. Instead, decision-making could be more related to beliefs, some of which may not be easily modified by facts.

And what are those beliefs? Some parents believe that HPV vaccination will increase sexual promiscuity, possibly by encouraging more sexual risk-taking owing to protection from the vaccine. And given the HPV vaccine provides no protection against viruses like HIV, there is the risk of more illness, in addition to the potential for more pregnancies. While there is no persuasive evidence that sexual education or other health interventions have this effect, the fear among parents persists, and has been reported as a contributor to HPV vaccine refusal.

This brings us to the study published last week:”Effect of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on clinical indicators of sexual behaviour among adolescent girls: the Ontario Grade 8 HPV Vaccine Cohort Study.” The full-text article is available from the Canadian Medical Association Journal. This study used administrative databases to look at two groups of grade 8 girls: pre-vaccine (2005-7) and post-vaccine (2007-9). The vaccine receipt status on each girl was obtained, and then indicators of sexual behaviour (pregnancy, non-HPV sexually-transmitted diseases) were tracked through grade 12.

This was a large study. The initial cohort was over 260,000 girls and they were followed for an average of 4.5 years. While only 51% received all three doses of the vaccine, less than 1% in the earlier cohort received the three doses. The results were reassuring. Across 10,000 pregnancies and over 6,000 sexually-transmitted illnesses, there was no statistically-significant increase in indicators of sexual behaviour related to receipt of the HPV vaccine. This was the case both for those that received the vaccine, and even those in the cohort eligible for the vaccine. (I won’t bother showing the graphs, as they’re essentially superimposable.)

Conclusion

Some parents fear that vaccinating girls against HPV will increase promiscuity. New research studying actual behaviours shows this worry to be unfounded. The HPV vaccine is safe, effective, and has the potential to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cervical cancer in the population. There are no substantive downsides to HPV vaccination. Despite this, vaccination rates remain suboptimal. This study may play a small part in addressing parental concerns and hopefully increasing the acceptance of this vaccine.

Reference

Smith L.M., E. C. Strumpf & L. E. Levesque (2014). Effect of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on clinical indicators of sexual behaviour among adolescent girls: the Ontario Grade 8 HPV Vaccine Cohort Study, Canadian Medical Association Journal DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.140900

Photo from flickr user Patricia H. used under a CC licence.