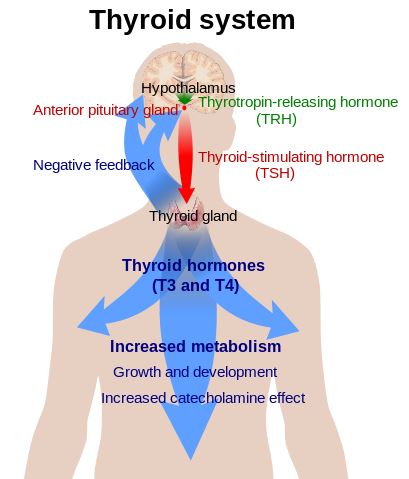

The thyroid system.

As glands go, we don’t give the butterfly-shaped thyroid that straddles our trachea too much thought — until it stops working properly. The thyroid is a bit like your home’s thermostat: turn it high, and you’re hyperthyroid: heat intolerant, a high heart rate, and maybe some diarrhea. Turn it down, and you’re hypothyroid: cold, tired, constipated, and possibly even depressed. Both conditions are associated with a long list of more serious health consequences. Between the two however, hypothyroidism is far more prevalent. The mainstay drug that treats it, levothyroxine (Synthroid), is one of the most prescribed in the world.

One of my more memorable pharmacy experiences involved levothyroxine. The store had recently changed its prescription labelling standards: It switched from listing the brand name, to only including the generic name (with the manufacturer in parentheses). Few patients noticed. But one elderly patient, taking Synthroid, was furious, and accused me of making a dispensing error. I assured her that levothyroxine was the active ingredient in Synthroid, and she was getting the exact same product as her last visit — but she would have none of it. Her symptoms had worsened, she said, because the medication wasn’t the same. “I want Synthroid — this levothyroxine stuff does not work,” she screamed at me across the counter. No amount of reassurance would satisfy her — I think we eventually resorted to custom, typewritten labels.

I mention this anecdote not to dismiss the symptoms of hypothyroidism as sensitive to placebo effects — hypothyroidism is a real condition with objective monitoring criteria. But this episode was one of my earliest lessons in understanding how perceptions can shape expectations of effectiveness — something that I’ll come back to, when we look at the controversies of this common condition. Any the treatment of hypothyroidism is not without its controversies – most of which occur outside the realm of medicine, and can more accurately be labelled pseudoscience.

Hypothyroidism is the consequence of the thyroid gland failing to produce enough thyroid hormone. The body produces two thyroid hormones: thyroxine (T4) and liothyronine (T3). Primary hypothyroidism is the result of insufficient production of T4 by the thyroid gland. (Secondary hypothyroidism is a consequence of pituitary or hypothylamic disorder.) The overwhelming majority of cases of hypothyroidism are primary, and the major cause of primary hypothyroidism is autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto thyroiditis). Iodine deficiency can cause primary hypothyroidism too, but it’s rare in developed countries. There are other causes of hypothyroidism, including drug therapies. But to keep this post to a reasonable length, I’ll restrict my focus to primary hypothyroidism, which seems to attract the most treatment controversy.

The prevalence of hypothyroidism varies with gender, age, the population surveyed, and the definition of hypothyroidism used. A recently completed large survey suggested an overall prevalence in America at 3.7% — presumably this will be similar in other countries where iodine deficiency is equally rare. Hypothyroidism is much more common in women compared to men., and increased in prevalence with age.

The presentation of hypothyroidism varies based on severity, from no symptoms at all, to severe cases with coma and organ failure. Patients with untreated primary hypothyroidism may describe weight gain, cold intolerance, dry skin/hair, constipation and hair loss. While the assessment and treatment of hypothyroidism is based around patient-relevant symptoms, the diagnosis of hypothyroidism must be based on lab tests, owing to the non-specific nature of the symptoms. Three laboratory measurements evaluate thyroid function and are used to diagnose hypothyroidism:

- Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH), secreted by the pituitary, is the primary screening measure in most situations. The normal range is usually reported to be 0.3-5.5 mIU/L, and a diagnosis of hypothyroidism is likely when the TSH is elevated above 10. The less functional the thyroid, the higher the TSH. (Values will vary for what is a “normal” TSH depending on the lab.)

- Free T4 (FT4) is evaluated when the TSH is abnormal. The usual range is 9-19 pmol/L and will be reduced in hypothroidism.

- Free T3 (FT3) has a usual range of 2.6-5.7 pmol/L. It may be reduced in hypothyroidism, but its value is not useful for diagnosis.

The treatments

The standard therapy for hypothyroidism is synthetic levothyroxine (LT4) alone, which supplies FT4 to the body. The body converts FT4 to FT3 as required. LT4 is effective for the vast majority of patients and is the mainstay of treatment guidelines. Many patients need to take nothing else; once their dose is determined, they take one dose a day, forever. LT4 is lifetime therapy. Benefits of LT4 include very accurate tablet standards, stable absorbtion and steady blood levels, and good tolerability.

Liothyronine (LT3) (Cytomel) is uncommonly used for thyroid dysfunction. The active form of thyroid, administration can cause wide fluctuations in FT3 levels, increasing the risk of cardiovascular harms compared with LT4. If LT4 is like gradually turning up your home’s thermostat, LT3 is akin to big fire in the fireplace – it can work quickly, but it’s difficult to maintain a consistent effect. With a less desirable risk/benefit profile, LT3 is generally used only in patients intolerant to LT4, or in those who are unable to successfully achieve treatment success and symptom resolution on LT4 alone.

Combination therapy (LT4 + LT3) occurs, but isn’t supported by good evidence, despite what you might expect from the testimonials. Trials comparing LT4 to LT4 + LT3 have shown no benefit over LT4 alone — and sometimes LT4 alone comes out on top.

Some physicians, patients and particularly alternative medicine purveyors advocate that dessicated thyroid (ground up pork thyroid) has advantages over LT4. This may be based in part on the naturalistic fallacy: the idea that using a “natural” thyroid source is better than “synthetic” levothyroxine. The evidence doesn’t support such a conclusion. In fact, judging by the evidence with LT4 + LT3, the evidence points the other direction. Dessicated thyroid contains a mix of T4 and T3. The lack of any randomized head-to-head comparisons make any comparison difficult, and renders claims of superiority unproven. While some patients seem to prefer it to T4 alone, the unpredictable stability, and potential for batch-to-batch variation make it less attractive from a patient perspective, and consequently treatment guidelines generally advise against its use. If combination therapy is felt to be necessary, using synthetic LT4 and LT3 together allows more precise and consistent dosing. Yet there exists a vast network of websites dedicated to locating sources of dessicated thyroid and shipping it to countries where it’s not available.

Treatment goals and monitoring

The assessment and treatment of hypothyroidism is based on symptoms, and is guided by laboratory monitoring. Monitoring includes measurements of TSH and more rarely FT4, with the goal of putting both into the “normal” range. And improvement can be rapid, usually starting within a few weeks, with significant improvement as levels normalize.

The controversies

Normal ranges

Laboratory monitoring is a critical component of evaluating thyroid function. Redefine what’s considered “normal” and you redefine what it means to by hypothyroid. While the upper limit of “normal” TSH is generally accepted to be around 5.5 mIU/L (it will depend in part on the lab standard), lowering the upper limit will move millions from “normal’ to “subclinical hypothyroidism”. There’s a debate as to whether the upper limit of a “normal” TSH should be dropped to 2.5 mIU/L. Confounding its critics, the medical “establishment” that is criticized online doesn’t yet seem convinced that revising the definition is necessary – which would create (on paper) millions of new patients. . Perhaps it’s because there’s no clear evidence of adverse consequences for not treating TSH values in the 2.5-5mIU/L range. So narrowing the range may do little for patient outcomes. Still, this is an area of continued controversy.

Subclinical hypothyroidism

Subclinical hypothyroidism is generally defined as a “normal” T4 and a slightly elevated TSH: That is, some laboratory signs of a thyroid dysfunction, but not sufficient enough to warrant a diagnosis. Symptoms are not always present, and can be vague and nonspecific: dry skin, constipation, depression, poor memory, etc. Subclinical hypothyroidism can only be diagnosed based on test results. The clinical significance of the condition is unclear. A recent Cochrane Review suggested that treating subclinical hypothyroidism doesn’t seem to result in meaningful differences in symptoms or quality of life, nor does it decrease cardiovascular morbidity. Given the risk/benefit perspective seems unclear, treatment decisions need to be individualized, and based on the severity of individual symptoms.

Screening

Routinely screening thyroid function in adults is controversial. Screening may be more reasonable in higher-risk patients (advanced age, family history, those with signs/symptoms, etc.). Screening would be expected to increase the likelihood of treatment and over treatment, and consequently exposure to the potential risks (not well understood) of long-term thyroid treatment. Given the uncertainty about the benefits of treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, screening may not be necessary in those at low risk and free of typical symptoms.

Is measuring FT4 enough?

Guidelines recommend routine monitoring of TSH and FT4, but not FT3, as T3 is felt to vary too significantly to normally guide treatment (though it may be useful when LT4 therapy is initiated). The alternative approach discounts the evidence and guidelines and advocates treatment with LT3 alone, or a combination of LT4 and LT3. At the extreme, some groups advise against laboratory monitoring and suggest relying on symptoms alone. It’s the alternative approach that may have driven the continued interest in dessicated thyroid, which persists on the market despite quality control and dosing challenges.

Switching brands and using generics

Some countries carry multiple brands of levothyroxine, and regulators may allow brand substitution – that is, they are deemed to be interchangeable. But even in settings where switching is permitted, health professionals generally try to keep patients on the same brand, to minimize the remote chance of any variation in effects due to formulation. (So the protestations of my customer, if not based in science, were consistent with usual pharmacy standards.) Looking at the data, however, there’s probably more variation in absorption based on food effects than any potential variation between brands. And the FDA recently tightened the quality standards for all brands, reducing the likelihood of variation between tablets or between brands. Still, taking the daily dose at the same time each day is probably equally important to maintaining stable blood values.

The pseudoscience

Are lab measures enough? Or even necessary?

A popular alternative approach to thyroid treatment is body temperature measurements, which are felt to be a proxy for thyroid function. While it sound plausible and could give you the impression of “taking control” of your hypothyroidism, there’s no persuasive data to link the two. Body temperature does not accurately measure thyroid function and should not be used to guide treatment.

Over-the-counter supplements

There are several over-the-counter thyroid supplements on the market, some of which contain animal-sourced thyroid gland. A recent study tested these supplements: 9 of the 10 had animal hormones present, some with amounts comparable to prescription drugs. Given the questionable quality control and potential for batch-to-batch variation, OTC supplements are a potentially dangerous choice for treatment.

Beyond the glandular products, there are a host of nutritional products targeted at consumers with hypothyroidism. Some of the common ingredients include:

- Kelp and other products that are sources of iodine; however, iodine deficiency isn’t an issue for most.

- Dong Quai, tyrosine, pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), ashwagandha, bladderwrack, schisandra, ginseng (Siberian and American), astragalus, rhodiola, selenium, zinc, copper and dozens of other ingredients that haven’t been demonstrated to have any meaningful effects — or to actually address the root cause of the condition.

Regulators like Health Canada don’t make it any easier: they approve multivitamins and iodine-containing supplements with “thyroid” in the name, or with recommended uses like, “Helps in the function of the thyroid gland” which, while not entirely incorrect, are misleading, given iodine or vitamin deficiency isn’t a relevant contributor to most cases of hypothyroidism. I could label the same supplements, “Helps in the function of the index finger” and be equally accurate.

You brought this on yourself

Well, that’s what Christaine Northrup suggests:

It’s no coincidence that so many more women than men have thyroid problems. Thyroid disease is related to expressing your feelings, something that until relatively recently had been societally blocked for women for thousands of years. In order to have your say—and maintain your thyroid energy—you must take a fearless inventory of every relationship in which you feel you don’t have a say. Ask yourself why you don’t. Are you a silent partner in a relationship? Does your partner make all the major decisions? Is it worth it? Did your mother have her say? In what ways are you like her?

Depending on your answers, I would urge you to skillfully and empathetically begin to say what is on your mind regarding the decisions that affect your life. Make sure that when you say what’s on your mind, you do so at the right time and remain detached from the effects. In other words, try not to force your will on others. For example, it’s okay to tell your best friend that you are worried about the character of her new boyfriend, but be aware that she may not necessarily be ready to hear your remarks. It’s not appropriate to “turn up the volume” as she’s rushing out the door to meet this new man.

OK, Dr. Northrup, I’ll try saying what’s on my mind. This advice is unadulterated magical thinking. Stop blaming women for autoimmune disorders.

It’s the adrenals

No, hypothyroidism is not adrenal fatigue – a made-up condition without any demonstrable evidence that it actually exists. Given the “symptoms” of adrenal fatigue overlap with those of hypothyroidism, screening for hypothyroidism is an appropriate element of any workup for unexplained fatigue. The same applies to taking hydrocortisone for hypothyroidism – while there are recommendations online, there’s no good evidence to show this is either safe or effective.

A little boost to help me lose weight

The thyroid is a convenient villain when confronting weight loss. If I can toss in a final anecdote, I had my Labrador Retriever’s thyroid function evaluated when she became sluggish and gained 20lbs over 12 months. It turns out, she actually was quite hypothyroid, and her activity level and weight responded well to levothyroxine, calorie restriction, and more exercise. In the obese, hypothyroidism is rare in the absence of other symptoms. And if there’s no hypothyroidism, manipulating thyroid hormones is inadvisable.

Making sense of it all

While there’s a lot of dissatisfaction with thyroid treatments online, the vast majority of patients find levothyroxine to be a simple and highly effective daily therapy. There are some true controversies in the treatment of hypothyroidism, but they’re buried in vast amounts of pseudoscience and bad treatment advice. So I advise my newly diagnosed patients against complicating treatment unless it’s necessary, and to start treatment with positive expectations: Synthroid is a top dispensed drug for a reason: It works. And despite the controversies, and the outlier opinions, the medical consensus on the treatment of hypothyroidism is quite strong. That means ignoring the noise, focusing on the relevant outcomes, and taking a stepwise, science-based approach to treatment.

Other references

Desiccated thyroid vs. synthetic thyroid supplementation. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter 2008;24(10):241013.

Towards Optimal Practice. Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group. Thyroid Dysfunction.

Disclosure: Scott treats his Labrador Retriever with levothyroxine.