At the end of September, President Donald Trump announced that his administration will allow the importation of prescription drugs from Canada as a strategy to reduce prescription drug prices for Americans. This isn’t allowing Americans to cross into Canada to have their prescriptions filled. (The border is closed, by the way). Rather, this is a bulk importation scheme that would potentially move large quantities of drugs from Canada to various states. While seen by some as an election gift to Florida, this announcement is also responsive to requests from other states, like Vermont, Colorado and others. Federal endorsement of these state-based proposals is a significant pivot away from previous positions which have strongly rejected this approach, citing (among other reasons) an unacceptable risk to consumers. So what’s changed? Is this actually feasible, and will it lower drug prices for Americans? And what will this do to Canadians?

At the end of September, President Donald Trump announced that his administration will allow the importation of prescription drugs from Canada as a strategy to reduce prescription drug prices for Americans. This isn’t allowing Americans to cross into Canada to have their prescriptions filled. (The border is closed, by the way). Rather, this is a bulk importation scheme that would potentially move large quantities of drugs from Canada to various states. While seen by some as an election gift to Florida, this announcement is also responsive to requests from other states, like Vermont, Colorado and others. Federal endorsement of these state-based proposals is a significant pivot away from previous positions which have strongly rejected this approach, citing (among other reasons) an unacceptable risk to consumers. So what’s changed? Is this actually feasible, and will it lower drug prices for Americans? And what will this do to Canadians?

Importation? Or Reimportation?

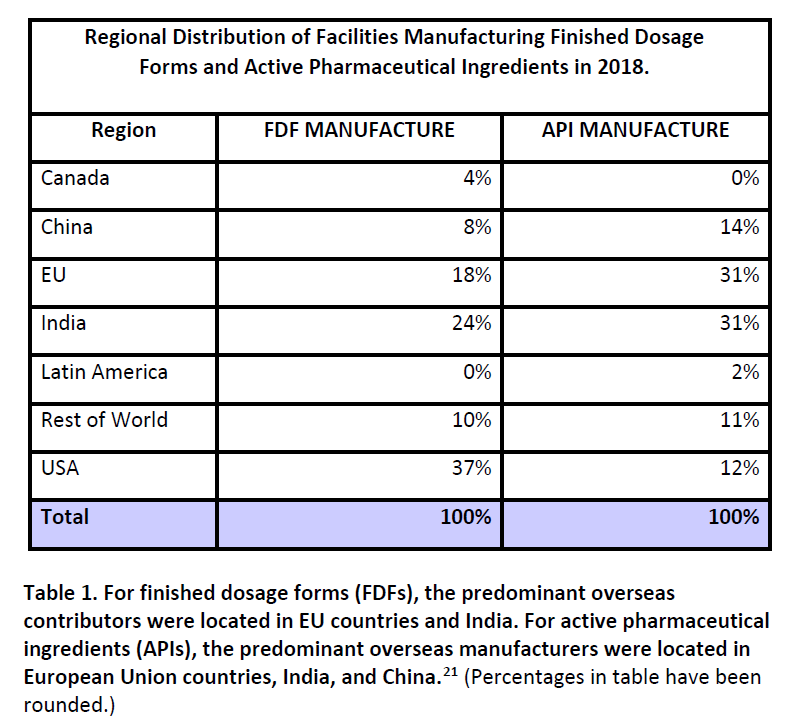

It’s called “importation” from Canada, but that may not be the most accurate term. Reimportation of drugs, manufactured in the US, is more likely. The prescription drug business is enormous, with a handful of massive companies operating as global entities. While head offices may be in the US, Europe, or elsewhere, companies have a presence in each country they sell in, to market products according to that country’s standards and requirements. However, it isn’t economical for every company to make each drug in every country. Most prescription drugs are manufactured in a small number of facilities for worldwide distribution – in some cases, the entire world’s supply of a drug may come from one single facility. Finished Dosage Forms (i.e., final prescription products) or Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API) (i.e., the raw material) constantly move around the world to supply local needs. This table, from a 2019 FDA Report on Drug Shortages, identifies that Canada has few facilities that manufacture for the US market:

Finished dosage forms for American prescription drugs are most likely to originate from facilities that are within the US (37%) followed by India (24%) and the European Union (18%) compared to Canada (4%). It is far more likely that a prescription drug that might be “imported” from Canada actually originated in the United States, and is being reimported than a drug was manufactured in Canada and would then be “imported” into the United States. This should not be a surprise, as Canada, while massive in geography, is tiny by population, with just 37.8 million residents – roughly a tenth of the USA. Canada’s entire population is just slightly smaller than that of California. Its pharmaceutical market, as expected, is also relatively small, making up only 2% of the world’s market (compared to America’s disproportionate 44%).

What is this strange northern land of lower cost prescription drugs?

Much is made of Canada’s universal healthcare system. The Canada Health Act defines the overarching principles of medicare, and stipulates that some health services must be provided at no charge (e.g., physician services, hospital care) to all residents. Canadian provinces are responsible for the delivery of health care to their residents, not the federal government. In general prescription drugs are not covered under the Act, so there is no guarantee of universal, no-cost access. Canada’s prescription drug system, consequently, is broadly similar to that of the US. Each province has its own programs to help residents pay for drug costs, and may determine eligibility based income levels (e.g., social assistance), age (e.g., seniors), or overall drug costs (e.g., catastrophic cost coverage). There may be copays and deductibles in these programs. Many Canadians receive insurance for prescription drugs through their employer, with programs that also have copays and deductibles. The result is that Canadians rely on a mix of paying cash, public insurance, and private insurance programs in order to obtain prescribed drugs.

Where Canada differs significantly from the United States is in how manufacturers establish pricing for their pharmaceuticals. The Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB), an independent quasi-judicial tribunal, regulates the maximum price of all patented (i.e., non-generic) prescription drugs. From their website:

Patentees are required by law to file information about the prices and sales of their patented drug products in Canada at introduction and then twice a year until the patent expires. The Patent Act along with the Patented Medicines Regulations set out the filing requirements.

The PMPRB reviews the average price of each strength of an individual dosage form of each patented medicine. In most cases, this unit is consistent with the Drug Identification Number (DIN) assigned by Health Canada at the time the drug is approved for sale in Canada.

There are five factors used for determining whether a drug product is excessively priced, as outlined in section 85 of the Act:

- the prices at which the medicine has been sold in the relevant market

- the prices at which other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in the relevant market

- the prices at which the medicine and other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in countries other than Canada

- changes in the Consumer Price Index

- any other factors that may be set out in regulations

One of the key features of this approach (that is also being studied in the US) is the benchmarking of list prices against other countries. The PMPRB determines what the Canadian “non-excessive” price should be, based in part on an examination of pricing in a ‘basket” of countries (currently: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). From this basket of prices, the median international price is identified. Because the US price is typically an outlier (as it is usually much higher), the Canadian price that is ultimately determined to be “non-excessive” is more closely aligned to the rest of the international comparators, and often significantly less than the US price. Manufacturers do not have to sell any drug in Canada, but if they choose to, they must comply with the PMPRB requirements.

Not all drugs are publicly funded by public or private drug insurance plans. There is an established process in Canada of health technology assessment to evaluate the value of new drugs which is similar to programs that exist in other countries. Pharmaceutical manufacturers may negotiate additional confidential discounts with public and private insurers when drugs are not felt to offer value-for-money based on their list price, even when that price is felt to be “non-excessive”. Canadians that pay cash for their prescriptions, however, can be assured that the PMPRB’s rules ensures that their prescription prices are benchmarked and monitored, and the list prices cannot be arbitrarily increased by the manufacturer over time.

What drugs are we talking about?

High prescription drug costs are a challenge facing all health systems around the world. But the USA is an outlier, with very high prescription drug prices that often continue to rise over time, and a real patchwork of programs that leave many Americans without comprehensive prescription drug insurance. Canadian list prices (compared to most other countries) are high, but on balance, are significantly lower than the US. It is worth reiterating that that this process of benchmarking and monitoring list prices applies to patented (brand name) drugs only (i.e., no generic equivalent exists). Generic prices are a different matter. Once a drug loses its patent, any manufacturer can potentially make it, and the generic drug market in the US is large and very competitive. Generic drugs have traditionally been cheaper in the US compared to Canada, and while Canadian generic prices have been dropping over past several years, I don’t think there is anything in Canada anywhere close to something like Walmart’s $4/month generic drug pricing.

How would importation actually work?

Let’s take the Florida model as an example. Based on the Florida proposal, (see “Canadian Prescription Drug Importation Concept Paper“) the state would select a vendor, who would contract with a wholesaler in Canada. The Canadian wholesaler would then presumably buy drugs from Canadian-based pharmaceutical companies, and then supply that Canadian-labelled drug (in bulk quantities) to a wholesaler in Florida. As per the state’s analysis:

Once the vendor identifies drugs that provide the highest potential for cost savings to the state, it must identify Canadian suppliers who are in full compliance with relevant Canadian federal and provincial laws and regulations and who have agreed to export the identified prescription drugs. The vendor must verify that these Canadian suppliers meet all of the requirements of the program, will meet or exceed federal prescription drug tracking and tracing requirements, and will export prescription drugs at prices that will provide cost savings to the state.

There is a long list of exceptions which include any biologic drug (e.g., insulin, some drugs to treat cancer, or autoimmune diseases), any injectable drug, and any controlled drug (e.g., narcotic). The bill requires the importer to validate the quality and safety of imported drugs, including laboratory testing of products. (It should be noted that Health Canada’s regulatory and manufacturing standards are largely equivalent to those of the FDA’s, but importation could increase the risk of counterfeit drugs entering the market.) There would be no difference for shoppers at the pharmacy level, but the drugs coming from Canada would have different labeling and identifiers, which might include tablet markings, etc. The proposal assumes that these drugs would be relabelled to meet US requirements. (Who would do this is unclear.) Patients would access their prescriptions at their pharmacy as per usual – there would be no need for residents to do anything different. Presumably, any savings from the importation and relabelling would be passed on to the consumer, and wouldn’t be sucked up by other middlemen in the process. Florida’s concept paper estimates savings of over $150 million per year. In contrast, an analysis of Vermont’s proposal suggested the cost of implementing an importation program would outweigh the savings.

So what’s stopping this process? Until just recently, it was the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Since 2003, it has had the power to approve importation programs. But no administration (Republican or Democrat) has ever approved one.

About-face? Or calling the state’s bluff?

In July 2019 the HHS and the FDA announced what it called a “Safe Importation Action Plan” which advanced the framework for drug importation, and removes federal barriers to states that want to try this approach. Two pathways were described:

- Pathway 1 allows states, wholesalers and pharmacists to propose “demonstration projects” for importation of drugs from Canada. Participants need to prove that importation poses no additional risk to consumers.

- Pathway 2 allows manufacturers to reimport versions of their own drugs that they are already selling to foreign markets, and to sell them in the American market at lower cost.

If you’re scratching your head over the logic in pathway 2, you’re not alone. One commentary noted:

Certain manufacturers have recently begun to market lower cost versions of their drugs under different NDCs, as an alternative to the existing higher-priced version but unaccompanied by rebates. It is uncertain whether manufacturers who wish to offer lower cost versions of their existing drugs in the U.S. would find Pathway 2 more advantageous than simply introducing a new, lower cost version to the U.S. market (under a new NDC) without importing it.

Canadian opposition

An essential part of any importation plan is the willingness of pharmaceutical manufacturers and wholesalers in Canada to support exports, and for the Canadian government to approve it. Like every other country, drug shortages are not uncommon in Canada and there are concerns that any large-scale importation scheme would quickly lead to drug shortages for Canadians. One paper examined the potential for this and concluded that substantial importation would completely deplete the Canadian pharmaceutical drug supply within several months:

The risks are high for the Canadian health care system if the U.S. were to legalize drug importation, unless Canada has a dramatic increase in domestic drug manufacturing shipments and/or a dramatic increase in the supply of imported prescription drugs. Without these, the threat to the Canadian drug supply is real. Drug shortages will undoubtedly occur.

Canadians are understandably concerned about the potential for its own drug supply market to be severely disrupted. While its own prescription drug pricing and funding system is not perfect, it is not equipped to deal with a surge in demand driven by millions of Americans. Health Canada is now expected to take legislative steps to oppose any importation plan. A statement says it will “take action to ensure Canadians have uninterrupted access to the prescription drugs they need”. These steps could include prohibiting bulk exports of products manufactured and labelled for the Canadian market, or requiring export permits on all exported drugs, to both increase the export price and/or limit the size of the export market.

The other group that is expected to strongly opposed this plan are pharmaceutical manufacturers on both sides of the border. It is unlikely any pharmaceutical company in Canada would be willing to increase its supply just for that supply to be shipped to the US, when an American affiliate is already selling the exact same product at what may be a much higher price. No Canadian pharmaceutical company would likely compromise their ability to meet Canadian demand, simply to see that supply shipped to the US. Innovative Medicines Canada, which represents these companies, has stated,

Canada cannot supply medicines and vaccines to a market ten times larger than its own population without jeopardizing Canadian supplies and causing shortages.

Canada isn’t America’s pharmacy

Importing Canadian-sourced pharmaceuticals is an idea that is unlikely to be workable at scale, and could very well be blocked by Canada before it ever gets off the ground. If implemented, it could lead to severe drug shortages for Canadians. Even then, it would still not solve the prescription drug price problems that face millions of Americans. Because the fact is that Americans don’t need Canadian drugs. They need Canadian drug prices. And that’s possible without any importation at all. America is the world’s largest pharmaceutical market and there is no reason why it cannot have the most competitive pricing in the world. There is nothing stopping it from implementing pharmaceutical policies (already in place in Canada and elsewhere) that make pharmaceutical drugs more affordable for consumers. But it will take an acknowledgement of ownership of the problem, and a willingness to make the hard decisions to bring affordable drugs to more Americans.

Disclosure: The author is a Canadian. And a pharmacist.

Photos from flickr users Wellness GM and David Goehring used under a CC license.