Last week I discussed the dismal results of the “Gonzalez Trial” for cancer of the pancreas,* as reported in an article recently posted on the website of the Journal of Clinical Oncology. I promised that this week I’d discuss “troubling information, both stated and unstated [in the report],” and also some ethical issues. More has come to light in the past few days, including Nicholas Gonzalez’s own voluminous, angry response to the JCO article. I’ll comment upon that below, but first a brief review.

The trial was begun in 1999 under the auspices of Columbia University, after Rep. Dan Burton had pressured NCI Director Richard Klausner to fund it. It was originally conceived as a randomized, controlled trial comparing the “Gonzalez Regimen” to standard chemotherapy for cancer of the pancreas. In the first year, however, only 2 subjects had been accrued, purportedly because those seeking Gonzalez’s treatment were not willing to risk random assignment to the chemotherapy arm. In 2000, the protocol was changed to a “prospective, cohort study” to allow potential subjects to choose which treatment they would follow. Gonzalez himself was to provide the ‘enzyme’ treatments.

After that there was little public information about the trial for several years, other than a few determination letters from the Office of Human Research Protections and a frightening account of the experience of one subject treated by Gonzalez. By 2006 or so, those of us who pay attention to creeping pseudomedicine in the academy were wondering what had become of it. About a year ago we found out: the trial had been quietly “terminated” in 2005 after it met “pre-determined stopping criteria.” As explained here, that meant that the Gonzalez group had not fared well.

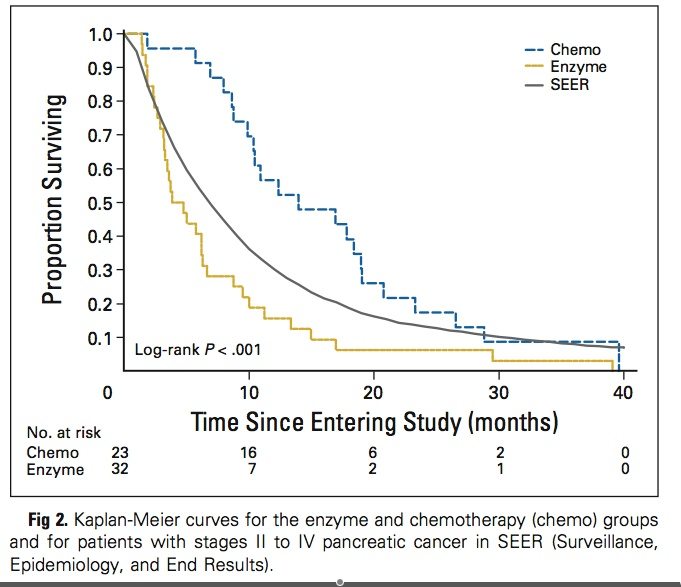

Four years after the trial’s ‘termination,’ the report was finally published: The Gonzalez cohort had not only fared much worse than the cohort that received chemotherapy, but it had fared worse than a comparable group of historical controls. Here, again, is the survival graph from the JCO paper:

The Gonzalez group had also fared much worse in ‘quality of life’ scores, which included a measure of pain.

Now let’s read between the lines. Forgive me for taking shortcuts; I’m a little pressed for time.

Problems: Stated and Unstated

The Authors

The first, glaring omission from the paper is Gonzalez’s name among the authors. I’ll discuss that below, together with observations about his posted response to the publication of the report.

The “Introduction”

Here is the entire rationale offered for having performed a trial of the Gonzalez regimen:

The Scottish embryologist John Beard first proposed pancreatic proteolytic enzyme treatment in 1906 and soon after published a monograph, entitled The Enzyme Therapy of Cancer. In 1981, Nicholas Gonzalez began to evaluate the use of proteolytic enzyme therapy. Twelve years later, in 1993, he was invited to present a series of cases at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which led him to undertake a case series of alternative medical therapy that included proteolytic enzymes, diet, nutritional supplements, and detoxification procedures. Among 11 patients with inoperable, biopsy-proven, stages II to IV pancreatic adenocarcinoma, he reported 81% survival at 1 year and 45% at 2 years. Four of the 11 patients survived for 3 years.

…

As a result of [the] bleak survival reports [of standard treatment] and the promise of proteolytic enzyme therapy, the NCI, in November 1998, funded a randomized, controlled, phase III trial.

What’s missing:

- A discussion of Beard’s quaint proposal in light of current knowledge.

- The common sense observation that a century ought to have been enough time for this ‘theory’ to declare itself one way or the other (it did, of course).

- The NCI’s inviting Dr. Gonzalez to present his case series had been motivated not by scientific interest, but by political pressure that had been building since the demise of Laetrile, as explained here, here, and here.

- There was no promise of proteolytic enzyme therapy. It was implausible to begin with, and Gonzalez’s case series was not valid, as explained here, here, and here.

- Quotation marks around the word “detoxification.” Or better, an explanation.

- The real reasons that the NCI funded the trial.

My opinion of what’s missing is not merely my opinion. According to the JCO “Information for Contributors” page:

At the 2008 ASCO Annual Meeting, Editor-in-Chief Dr. Daniel Haller spoke on “How to Write an Outstanding Manuscript.” In his lecture, Dr. Haller shared tips on how to write and submit your manuscript, an overview of the publication and review process, considerations for journal editors and contributors, and more. To view click here.

If you do that, here’s what you’ll find in Dr. Haller’s talk:

For Phase III clinical trials, follow CONSORT guidelines closely.

CONSORT stands for Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. Here is part of its statement regarding “The Introduction”:

Typically, the introduction consists of free-flowing text, without a structured format, in which authors explain the scientific background or context and the scientific rationale for their trial…Authors should report the evidence of the benefits of any active intervention included in a trial. They should also suggest a plausible explanation for how the intervention under investigation might work, especially if there is little or no previous experience with the intervention. The Helsinki Declaration states that biomedical research involving people should be based on a thorough knowledge of the scientific literature. That is, it is unethical to expose human subjects unnecessarily to the risks of research…

We’ll continue to reference the CONSORT statement as we look at…

The Methods

The study intervention: Authors should describe each intervention thoroughly, including control interventions…In some cases, description of who administered treatments is critical because it may form part of the intervention. For example, with surgical interventions, it may be necessary to describe the number, training, and experience of surgeons in addition to the surgical procedure itself. When relevant, authors should report details of the timing and duration of interventions, especially if multiple-component interventions were given.

From the report of the Gonzalez trial:

Proteolytic Enzyme Treatment

The enzyme treatment included orally ingested proteolytic enzymes, nutritional supplements, detoxification, and an organic diet (unaltered from the pilot study). Patients received three pancreatic enzyme and two magnesium citrate capsules with each meal. The patients also took specified numbers of capsules with magnesium citrate and Papaya Plus every 4 hours on an empty stomach. The dose for patients with stage II disease was 69 enzyme capsules, and the dose for patients with stages III or IV was 81 capsules per day. After day 16, patients had a 5-day rest period and then resumed treatment on day 22. Treatment could be adjusted by the physician and could be increased for cancer progression. A diet that required at least 70% of the food to be raw or minimally cooked was required. All food was organic. Prescribed detoxification procedures included coffee enemas twice each day; skin brushing and cleansing; salt and soda baths; and a liver flush, clean sweep, and purging.

Questions:

- Would the physician know how to adjust the treatment for cancer progression, when the treatment has never been studied in a systematic way?

- How would the physician even know if there had been cancer progression, if he believes that “pain might be an indication that the tumors were being dissolved, and that [the patient] could expect weight loss as he was detoxifying his body”?

- What is the meaning of “detoxification” in this context? How could a coffee enema be considered a detoxification procedure? How could skin brushing be considered detoxification? Where is the evidence that there are special toxins on the skin of people with cancer of the pancreas, or that removing them might have anything to do with its treatment?

- What is a “liver flush”? What is a “clean sweep”? These are not coherent medical or scientific terms. In a scientific report, neologisms must be defined and their rationale explained.

- What about advising subjects to have the fillings removed from their teeth? There is no mention of that in the methods, but we know that Dr. Gonzalez advised at least one subject to do that.

Another pertinent passage:

Patients in the experimental arm received proteolytic treatment under the care of a practitioner familiar with the regime…

That practitioner was Gonzalez himself. Wasn’t this important enough to mention in the report?

The Discussion

Pertinent excerpts:

Little is known about…the benefits or harms of alternative medicine used in place of conventional, evidence-based treatments [for cancer].

Oh really? Actually, quite a lot is known, and none of it is good.

This report may be among the first…to compare allopathic treatment to an alternative medicine program…

Ouch! The A-word is a dead give-away that the authors know little of their topic. And let’s hope that this is the last such report, for reasons introduced in this passage:

Despite the intent of all the investigators involved to complete the study as an initially planned (ie, a randomized, controlled trial), physicians and patients were strongly committed to their own beliefs. Unless physicians convey clinical equipoise and sincere uncertainty about which treatment is better, patients rarely submit to random assignment, especially in the setting of a lethal disease.

The problem is that there was not clinical equipoise, period. There was never a consensus among experts in cancer medicine or cancer biology that the Gonzalez Regimen was even remotely likely to be comparable to the best current treatment, even for a chemotherapy-resistant tumor such as cancer of the pancreas. Dr. Chabot, the Principal Investigator, stated as much when he first advertised the trial—without, apparently, realizing the implication. If either subject accrual or subject compliance in the trial was compromised by oncologists warning patients away from the Gonzalez regimen (as Gonzalez maintains happened), that meant only one thing: that the trial never should have begun, because it did not satisfy a fundamental ethical requirement.

That the authors failed to grasp that general truth is confirmed in this passage:

The findings in this study suggest that controlled studies of alternative medicine regimens are feasible…

Finally, this passage raises questions:

The unexpectedly long survival observed in the gemcitabine group also may have been due to the selection criteria and changes in supportive care (eg, better use of surgical procedures, antibiotics, pain medication, and noninvasive placement of biliary stents).

As I suggested in a comment last week, I believe that here the authors were comparing the survival curve of the gemcitabine group in this trial to survival outcomes in other chemotherapy trials—not to the survival curve of the Gonzalez group. Nevertheless, the passage raises the issue of possible differences in supportive care between the two groups in this trial. There almost certainly were such differences, as evidenced by the experience of Susan Gurney’s friend and as now claimed by Gonzalez himself:

For those subjects destined to receive chemotherapy, Dr. Fine had at his disposal the resources of Columbia, a team of expert senior physicians, researchers, fellows (oncologists in training), residents, highly skilled oncology nurses and other support personnel, and all the high tech facilities one could wish for. According to his own statements, he and his highly motivated team employ all the benefits of modern academic, hospital based medicine, sparing no intervention, withholding no aid to keep patients alive – even to the point of repeated surgeries, and paracentesis (removal of abdominal fluid) done 2-3 times a week, a procedure rarely in the past pursued so determinedly. Those under Dr. Fine’s charge could not ask for more intense or sophisticated care, from an enthusiastic, supportive staff at a major academic institution. Our patients, on the other hand, faced quite a different and often grim situation at the hands of local doctors at best indifferent and frequently hostile to our therapy.

…

Of all the nutrition patients, only one – who ultimately survived 3.5 years – received anywhere near the level of intensive supportive care and encouragement given the chemotherapy patients. In this unique situation, the local doctors coordinated their treatment with me, realizing full well that he was sustaining a most unusual response. In no other case did the local doctors encourage aggressive intervention to keep the patients alive and also on the nutritional therapy. The general physician attitude toward our patients could not be in sharper contrast to the enthusiastic team approach of Dr. Fine, whose talented staff appear to have one ultimate, determined goal with all their intensive care, to keep patients alive as long as possible and on treatment as long as possible.

I regard this complaint by Gonzalez, even if true, as disingenuous. If he felt that way at the time, he should have kicked and screamed it from the rooftops. Why didn’t he mention it in his complaint to the OHRP? We find nothing of the sort in either the two, pertinent determination letters (here and here) or in Gonzalez’s rebuttal to those letters. What we know about Gonzalez’s practice style is that his response to signs of complications or disease progression has been to deny, ignore, rationalize, or otherwise ‘treat’ them with his ‘regimen’ (look here under “A Clinically Competent Medical Person?”). I suspect that he thought of this complaint only after reading the JCO report.

Gonzalez’s sudden enlightenment notwithstanding, a parity in supportive care between the two groups would almost certainly not have changed the survival differences in any important way. It might have changed the ‘quality of life’ differences, however, particularly regarding pain. In any case, for both scientific and ethical reasons there should not have been such a disparity, and since many ‘supportive care’ interventions were not part of the formal protocol they should have been reported in the JCO article, as required by the CONSORT standards for reporting results:

Authors should report all departures from the protocol, including unplanned changes to interventions, examinations, data collection, and methods of analysis.

Gonzalez Answers More Questions

In his posted response to the JCO article, Gonzalez has answered several of the questions that we’ve posed over the last couple of years. He was, as we suspected, the author of the last complaint to the OHRP: the one that, ironically, resulted in our discovering what had happened to the trial. His identity as the complainant is made clear by his unhappy response to the OHRP’s findings, and also by a piece written in 2008 by his friend, ‘Harkinite’ Ralph Moss–which I hadn’t noticed until last week (thank you, Peter Moran).

Second, we have a pretty good idea why it took the Columbia team so long to publish the report. Gonzalez tacitly threatened the authors and Columbia with serious repercussions if they did so, and given his relations with powerful politicians Dan Burton and Tom Harkin, he may actually have been able to deliver on that threat (maybe he still can). In a 2006 letter to Lee Goldman, Dean of the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Gonzalez warned that Burton and Harkin had already leaned on then-NIH Director Elias Zerhouni on his behalf. We are also told, in that letter, that a manuscript of the trial report had been submitted to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) at some time during 2006–unbeknownst to Gonzalez until he was phoned by the oncology editor. According to Gonzalez, who had not been listed as one of the authors, JAMA rejected the manuscript after that phone conversation.

This information, together with Susan Gurney’s having reported that PI Chabot would “not come forward and say anything publicly ‘according to the advise of his lawyers’ –which from what I understand are the Columbia Institution lawyers,” suggests that Columbia really was cowed, for a time, by Gonzalez’s threats. This is not a valid reason for having deprived desperate cancer patients of the results, of course. I wonder what changed recently?

Third, we have a damn good idea why Gonzalez wasn’t listed as an author, or even as the “participating alternative practitioner“: that he, or perhaps the Columbia Institution lawyers, had warned against it. Gonzalez, by the way, stumbles badly in his long complaint to Dean Goldman when he writes:

I had no knowledge of any “manuscript preparation” in progress, I was never invited to discuss the manuscript during its preparation, and I never heard from anyone about a manuscript until Dr. Pasche of JAMA called me on December 3, 2006. I was rather surprised, to say the least, to learn from Dr. Pasche that without my knowledge a paper had been written…

Hmmm. On the previous page, Gonzalez mentions a “research team meeting” in June, 2006, to which he had been invited but did not attend. One of the agenda items for that meeting was “Discussion of data analyses and the preparation of the study manuscript.” Afterward, Dr. Gonzalez received the minutes of the meeting “promptly.” In his own words,

The notes do indicate…that Dr. Chabot and the others intended to publish and publicize the data as if the study had legitimately been brought to conclusion.

Gonzalez: The “data, in my opinion, [are] largely meaningless, and the controversies surrounding my work still unresolved“

Is this true? Was the trial so flawed that its reported results are meaningless? Gonzalez cites a 2005 letter from Dr. Linda Engel, “the official spokesperson of the NIH,” to support his contention:

…it appears as if the current design and implementation of the study may have resulted in accrual into the two study arms of patient populations that are not comparable. As a consequence, it is very difficult (if not impossible) to ascertain treatment effect with any certainty.

…

…it is highly likely (if not certain) that reviewers of the data from this study will raise substantive and legitimate concerns about the comparability of the two populations. As a consequence, it is virtually certain that the controversy surrounding the study will not be settled by the data from it.

Gonzalez’s representation of Dr. Engel as “the official spokesperson of the NIH” is misleading. What she was, at the time of her letter, was Special Assistant to the Director of the NCCAM. The Director was the late Stephen Straus, who, in a 2001 meeting discussing the Gonzalez trial, had worried that

Our ability to reach out and be open-minded about alternative therapies is constantly impugned by traditional medicine and others. We must press on, because this is groundbreaking and important.

As is the norm for NCCAM functionaries, Dr. Engel’s views were politically, not scientifically based. More about this below.

Dr. Gonzalez’s arguments are many, his writing voluminous and redundant, his tone paranoid and conspiratorial. Some of what he writes may be true, and if so speaks to the ethics of the trial and to some of the inadequacies of the report: among these are charges of inadequate informed consent procedures and of undisclosed conflicts of interest among some of the authors. The only charge that could possibly render the data meaningless, however, is that the two cohorts were sufficiently different, in their degree of disease progression, to explain the difference in reported outcomes. This, in my opinion, is demonstrably untrue.

To simplify the exercise, let’s see what happens if we ignore the gemcitabine arm altogether. We needn’t concern ourselves with it, because its better-than-previously reported outcomes, so rankling to Gonzalez and to Dr. Engel, are beside the point. What interests us about this trial is that the Gonzalez group did so poorly: worse than the SEER data for comparably staged cancer of the pancreas, and much worse than Gonzalez’s previously reported, unsupervised case series. Gonzalez worries that PI Chabot saddled him with sicker patients than were allocated to the chemotherapy arm:

During one of the regularly scheduled group meetings held December 13, 2004 at Dr. Chabot’s Columbia office, at a time the clinical trial had been up and running for a full five years, Dr. Isaacs and I first became aware of a very significant difference in both the total number of patients entered into each arm, and the stage of their disease. By that time, 38 patients had been admitted for nutrition treatment, and of these, approximately 76% by our accounting had been initially diagnosed with the most advanced (stage IV) disease, the other 24% with earlier stage II or III. This pattern approximated, as did our pilot study, the usual distribution of newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients as reported in the literature.

…during that meeting, Dr. Chabot handed out a “data chart” which included the total numbers of patients admitted into each of the two groups, with the breakdown by stage. First, I was surprised that he had tabulated the numbers incorrectly for our group, which he reported incorrectly consisted of 35% at stage II and III and 64.7% at stage IV. But I was even more surprised to learn that the chemotherapy arm of the study, created under the direction of the Columbia oncologists, consisted of only 14 patients, 61.5% with earlier stage II and III disease, with only some 38% as advanced stage IV – a near reversal of the distribution in the nutrition group, and a reversal of the usual breakdown reported among patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Well, all right, for the sake of argument let’s assume that this happened. It would certainly have ethical implications, but what does it say about the efficacy of the Gonzalez regimen? In order to answer the question, consider another of Gonzalez’s statements from the same essay (emphasis added):

The literature reports only 5% or less of patients will be initially diagnosed with stage I tumors. Of the group categorized as “non-stage I” approximately 70-75% are classified at diagnosis as stage IV, the most advanced level, with 25-30% as stage II and III. In the Gemzar study from 1997, which excluded operable stage I patients, those entered into each arm fell into this range, with approximately 28% diagnosed as stage II and III, and 72% as stage IV. In our pilot study, which also disqualified those with operable disease, 8 of 11 patients, or 73%, presented initially with stage IV, and three as inoperable or locally advanced stage II, the numbers again conforming to the usual distribution of non-stage I subjects.

But the pilot study, which Gonzalez has just characterized as having a subject mix similar to the ‘enzyme’ group in the cohort trial, reported outcomes far better than those reported in the cohort trial. Forget about the chemotherapy arm in the current report: what’s interesting is the difference in outcomes of the ‘enzyme’ arm compared to the case series that had ostensibly justified the trial to begin with.

Gonzalez’s other, potentially data-damning charge is that the subjects allocated to his regimen were not capable of following it, for whatever reason: they couldn’t swallow, they had no one at home to help, etc. Again, to give him the benefit of the doubt, let’s look at the only statement in his rebuttal to offer a justified, quantitative estimate of the statistical damage that this may have caused. He argues that there ought to have been a “lead-in” provision, such that he could have given each prospective subject a 1-2 week trial period in order to determine if each was capable of following the regimen:

Had a lead-in been in play, even if only a week long as in the Gemzar study, we could have discounted, out of the total of 39 eventually admitted into the nutrition arm, 11 patients who never started the therapy or dropped out within the first seven days, all of whom died fairly quickly after their initial consultation with us.

Continuing to give Gonzalez the benefit of the doubt, let’s assume that those 11 were among the 32 eventually reported in the JCO. That leaves 21 who, by his estimation, would have graduated from the lead-in period into the study proper, of whom only 7 would have been alive at 10 months and 2 at 20 months (see the figure above). Not much better, that. Elsewhere, of course, Gonzalez writes that many more of his subjects were unsuitable:

Overall, we estimate that of the 39 patients Dr. Chabot ultimately approved for the nutrition arm, only 6-8 at most liberal analysis actually followed the regimen as prescribed to any significant degree.

Now we’re getting somewhere: if 21 could have begun the regimen, but only 6-8 could have continued it for any reasonable time after 1-2 weeks, then that’s really the point of an “intent to treat” analysis, isn’t it? Yet Gonzalez wants it both ways: “heads I win, tails you lose” is the way one commenter put it. The only thing about this special pleading that I find mildly interesting, although merely as a curiosity, is that it might explain how Gonzalez could be a true-believing crackpot rather than a charlatan. If he has, over the years, unwittingly used his arduous regimen as a survival test, it’s just possible that he actually believes it works—as mistaken as that is. I doubt this, because I don’t really believe the results of the case series, and in any event it’s irrelevant to the practical matter: the JCO report demonstrates that the Gonzalez regimen doesn’t work, and his objections do not change that.

More Problems

As suggested above, some of what Gonzalez has written, if true, is pertinent to the proper reporting of the trial and to its ethics, even if it does not negate the overwhelming conclusion. He writes that “39” subjects were “eventually admitted into the nutrition arm,” but only 32 were reported in the JCO. What happened to the rest? Throughout Gonzalez’s rebuttal materials are other numbers that don’t match those in the JCO report. According to CONSORT,

…it may be difficult for readers to discern whether and why some participants did not receive the treatment as allocated, were lost to follow up, or were excluded from the analysis. This information is crucial for several reasons.

Gonzalez also writes that most of the ‘enzyme’ subjects were enrolled early in the 5 or so years that the trial was active, while most of the chemotherapy subjects were enrolled in the later years. This does nothing to change my opinion of the important outcome, for which I’m not considering the chemotherapy cohort at all, but it does trigger CONSORT objections.

There are probably more quibbles, but enough.

Ethics Redux: What is the Responsibility of Journals?

This essay has added several, relatively minor points—other than the delay in publication—to the ethical arguments that I made a year and a half ago, here and here. I urge readers who haven’t read those pieces to do so. The JCO report and Gonzalez’s response to it do not change any of those arguments: the trial was overwhelmingly and horribly unethical, and never should have been done. It answered no legitimate scientific or medical question, because that had long ago been answered. It subjected unwary human subjects to the whims of a dangerous quack whose license to practice medicine had been nearly revoked, and should have been, several years before. It somehow bamboozled otherwise respected academics into colluding in the systematic torture of those subjects. It is Exhibit #1 in the case against politicians bullying the NIH into accepting their pet projects, but it is equally disturbing in its exposure of the involved biomedical scientists and administrators as the “spineless wonders” that they were. (Exhibit #2 is here).

I promised last week that I’d address the paradoxical question of whether or not the JCO should have published the report. In today’s post are many examples of problems in the manuscript that should have been, and possibly were, noticed by reviewers, but apparently were allowed to remain. Might that have been because correcting them would have made the article too embarrassing, or have made it unpublishable on the basis of pseudoscience alone? Consider, for example, trying to justify “a liver flush [and] clean sweep.” I wonder what discussions occurred in the editorial boardroom.

Even these objections are not the crux of why the JCO ought to have considered, and possibly did consider, not publishing the article. The crux is this unambiguous sentence in the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Health Organization, to which most medical journals, including the JCO, claim allegiance:

Reports of research not in accordance with the principles of this Declaration should not be accepted for publication.

Also see the American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement: Oversight of Clinical Research, published by the JCO.

It may seem like an impossible dilemma, at first glance. I’ve already stated that I’m happy that the results of this trial were finally made public, and that is true. Nevertheless, the admonition in the Helsinki Declaration can have no teeth if it is so easily flouted in a case as flagrant as this. I suggest that there were alternatives to merely publishing the article in its current form. The NIH, which funded the study, could have published the results on its own website, ClinicalTrials.gov. The NCI and the NCCAM, the relevant sub-institutions, could have publicized the results on their own websites, in order to get the word out to cancer patients and to “alties,” respectively. As of last week, there was a resounding silence at those locations. It seems as though the responsible governmental sources are less than anxious to do the only thing that can give this sordid affair even the possibility of doing some good for future cancer patients. It’s funny how the NCCAM exuberantly trumpeted the once-in-a-blue-moon “landmark study” that it viewed as having supported an implausible method (in spite of it having done nothing of the kind), but is reticent to publicize the many failures.

Finally, the JCO might have–and I hope still will, in its hard-copy edition–include an accompanying editorial acknowledging the ethical problems with the trial and the dilemma involved in choosing to publish the report. Recall that it was at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO), the organization that publishes the JCO, that Susan Gurney first learned “quickly and definitively” what the responsible investigators at Columbia would not tell her:

that the Gonzalez protocol was a fraud; no mainstream doctors believed it was anything else and they were surprised that anyone with education would be on it.

Clinical equipoise, there was not.

What Should Happen Now?

In a nutshell:

The New York medical board should strip Gonzalez of his license, now that their only reason for not having done so years ago has vanished. The authors of the report should be scrutinized by the OHRP and the NIH. They should be banned from being investigators in any NIH-sponsored trial for some finite period, and their involvement in the Gonzalez trial should become a noticeable smear on their reputations. NIH scientists and administrators should ‘cowboy up’ and refuse to be bullied by politicians, no matter how influential. If they must resign to make the point, they should do so loudly and clearly. President Obama and the American people should be wary of Tom Harkin becoming the next NIH legislative czar, and should use this episode to explain why. The NCCAM should be abolished. IRBs should be alerted that every time a proposal to study a “CAM” claim is submitted, there is a high probability of mischief.

I’m sure you can think of more.

* The “Gonzalez Regimen” Series:

1. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part I)

2. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part II)

3. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part III)

4. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part IV)

5. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part V)

6. The Ethics of “CAM” Trials: Gonzo (Part VI)

7. The “Gonzalez Trial” for Pancreatic Cancer: Outcome Revealed

8. “Gonzalez Regimen” for Cancer of the Pancreas: Even Worse than We Thought (Part I: Results)

9. “Gonzalez Regimen” for Cancer of the Pancreas: Even Worse than We Thought (Part II: Loose Ends)