Normally, I try to write my weekly post for this blog by Saturday. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, this weekend Sunday afternoon arrived, and I hadn’t yet written my post. Sure, I had started a post, but I wasn’t really happy with the topic or how it was coming out, which is probably why I hadn’t finished it by my usual time. Then, on Sunday afternoon, I started seeing stories like this one in The Washington Post:

On the eve of the Republican National Convention where President Trump hopes to revive his flagging political fortunes, he will announce the emergency authorization of convalescent plasma for covid-19, a treatment that already has been given to more than 70,000 patients, according to officials familiar with the decision.

In a tweet late Saturday night, White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said the announcement at 5:30 p.m. Sunday involved “a major therapeutic breakthrough on the China virus.” Officials confirmed on Sunday the treatment is convalescent plasma; they spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to discuss the issue. The White House declined to comment.

I must admit that when I heard about McEnany’s Tweet about an announcement of a “major therapeutic breakthrough” for COVID-19, I had a sneaking suspicion that it might be something like Oleandrin, the extract from the oleander plant whose utter lack of evidence of efficacy against COVID-19 (other than an in vitro study in cell culture) was discussed last week by our very own Steve Novella. It was just a sneaking suspicion, because, as has been discussed, oleander is toxic and there’s no evidence that it works against COVID in humans. That’s thin gruel even for Donald Trump to hold a press conference to make an announcement of a “therapeutic breakthrough”, even if the CEO and founder of MyPillow.com Mike Lindell had also endorsed Oleandrin. After all, if Anderson Cooper could slice, dice, and humiliate Lindell on live TV, I suspect that even Trump would be reluctant to come back for seconds.

So it makes sense that the announcement would be about a treatment with some biological plausibility, and this announcement gave me the chance to take a look at the current evidence for the use of convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19.

What is convalescent plasma?

The use of convalescent plasma to treat infectious disease is a very old concept, dating back over 100 years. In brief, the use of convalescent plasma is a form of passive immunization in which plasma from patients who have survived an infectious disease is collected and used to treat patients with active disease. The idea behind the use of this plasma is quite simple, namely that the antibodies against the disease present in the convalescent plasma will bind to the microorganism causing the disease and thereby help a patient with the disease mount an effective immune response against the organism.

Because I’m a history buff, I couldn’t resist reading a bit about the history of convalescent plasma as a treatment for infectious disease. Generally, it was thought that the first application of convalescent plasma for this indication was during the 1918 influenza pandemic, and, as noted in this article, there were several studies carried out during that pandemic suggesting that the plasma could be effective in decreasing mortality. A meta-analysis of eight reports from that time involving 1,703 patients was even published in 2006, confirming the benefit. True, the studies from the time were not randomized, double blind, or placebo-controlled, but the risk reduction for death was impressive, as this excerpt of the abstract shows:

Eight relevant studies involving 1703 patients were found. Treated patients, who were often selected because of more severe illness, were compared with untreated controls with influenza pneumonia in the same hospital or ward. The overall crude case-fatality rate was 16% (54 of 336) among treated patients and 37% (452 of 1219) among controls. The range of absolute risk differences in mortality between the treatment and control groups was 8% to 26% (pooled risk difference, 21% [95% CI, 15% to 27%]). The overall crude case-fatality rate was 19% (28 of 148) among patients who received early treatment (after <4 days of pneumonia complications) and 59% (49 of 83) among patients who received late treatment (after ≥4 days of pneumonia complications). The range of absolute risk differences in mortality between the early treatment group and the late treatment group was 26% to 50% (pooled risk difference, 41% [CI, 29% to 54%]). Adverse effects included chill reactions and possible exacerbations of symptoms in a few patients.

In actuality, though, this sort of therapy had been tried against polio in New York in 1916. The first documented use of convalescent plasma therapy was in Italy in 1906, when Francesco Cenci, a public health doctor working in a small town of Central Italy near Perugia, used serum from a 20 year old man who had just recovered from the measles to prevent measles infection in four children. Later in 1906, Cenci used convalescent serum to treat a child seriously ill with the measles complicated by pneumonia. Cenci also reported that a similar treatment had been made on two children in 1900, in the Pediatric Clinic of Rome directed by Luigi Concetti, that was thought to be the first to use serotherapy against diphtheria in Italy, after the seminal studies by Emil Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato. By way of additional history, the first reference to antibodies came from Emil von Behring and Shibasabura Kitasato in 1890, when they showed that the transfer of serum from animals immunized against diphtheria to animals suffering from it could cure the infected animals, although investigators had been experimenting with such methods going back to 1880 or so. In any event, Behring was later awarded the Nobel Prize for this work in 1901.

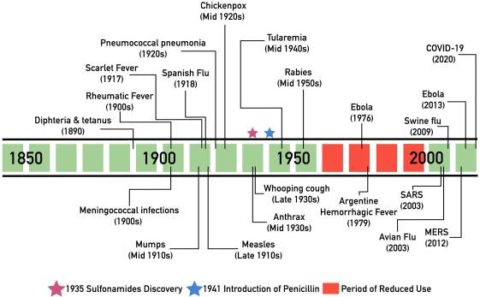

Since then, convalescent plasma has been tried and used for a variety of infectious diseases, with possible therapeutic efficacy claimed for the management of measles, Argentine haemorrhagic fever, influenza, chickenpox, infections by cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19 and, more recently, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), H1N1 and H5N1 avian flu, and severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) viruses. Convalescent plasma has also been used in Ebola virus disease, with some reports of success dating back to the 1970s, when the disease was first described. Unfortunately, most of the studies of convalescent plasma for various infectious diseases have been of low quality, and many weren’t randomized. Unsurprisingly, with the rise of antibiotics and other antimicrobial therapies in the mid 20th century, interest in convalescent plasma to treat infectious disease waned, only to reappear periodically whenever there is a new epidemic or pandemic for which there is no effective treatment; i.e., Ebola virus, H1N1 influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, and MERS in 2012. Indeed, successes using convalescent plasma for these latter two diseases established the precedent for using the same treatment for COVID-19.

Of course, the use of antibodies to treat a viral disease makes sense, although their use has had a mixed history. The concept is, as I mentioned above, simple, and well described in this article (from which the figure above was taken and is under Creative Commons license):

The convalescent plasma therapeutic approach is based on the principle of passive antibody therapy, a short-term strategy whereby antibodies from the blood of someone who recovered from an infection can be administered to protect or treat another person [6, 21]. Effectively, the end goal is the same as vaccines, making antibodies against a specific infectious agent readily available. For instance, a vaccine relies on the host immune cells (B lymphocytes specifically) to produce antibodies after antigen recognition and signal amplification by the immune system, a process that may take weeks [24]; on the other hand, in the case of passive antibody therapy, the process is expedited by providing a patient with immediate immunity when the premade antibodies are given. Therefore, for COVID-19 patients, the expedited approach could prove lifesaving. Nevertheless, this advantage does not come without caveats, as immunization with passive antibody therapy is typically of shorter-term protection, in part because of the half-life of antibodies in circulation [25] and lack of new production by B lymphocytes. Today, passive antibody therapy relies primarily on pooled immunoglobulin preparations that contain high concentrations of antibodies. In contrast, plasma has been used emergently in epidemics in which there is insufficient time or resources to generate immunoglobulin preparations [21].

The practicality of using pooled immunoglobulin preparations or convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19 during a pandemic is also questionable, given that immunoglobulins are a blood product that has to be collected from donors who have recovered from COVID-19, and it is questionable whether, even if it is effective, there would be enough supply to meet the needs of patients suffering from severe COVID-19 disease. Also, because convalescent plasma is a blood product, there is a non-zero risk of transmitting blood-borne disease from it. True, the risk is quite low, given how we now test blood products for viruses like hepatitis B and HIV, but it is not zero. Finally, antibody therapy generally is most effective when administered prophylactically or implemented early after the onset of symptoms.

Convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19: Does it work? Who knows?

There were already rumblings last week that something like this might happen, that Trump might push the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization (EUA), the same way he pressured the FDA to issue an ill-advised EUA for hydroxychloroquine, a drug that, according to the latest randomized controlled trials, does not work in severe or mild COVID-19 or work to prevent COVID-19 when used as prophylaxis after a known exposure to a person with the disease. Unfortunately, none of the increasingly negative evidence has stopped the propaganda or astroturfing promoting hydroxychloroquine as a “game changer” or way out of the pandemic, even after the FDA had revoked the EUA for the drug in June. For example, there was this Tweet on Saturday morning:

The deep state, or whoever, over at the FDA is making it very difficult for drug companies to get people in order to test the vaccines and therapeutics. Obviously, they are hoping to delay the answer until after November 3rd. Must focus on speed, and saving lives! @SteveFDA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 22, 2020

Regular readers know that I consider this sort of statement from the President to be very dangerous, as it is basically accusing the FDA of plotting against a COVID-19 treatment or vaccine that is safe and effective. Anyone who knows how the FDA works knows how ridiculous that accusation is. In addition, it’s a perfect sort of statement for COVID-19 deniers to point to, to bolster their claims of a conspiracy to bypass regulations in order to approve drugs and treatments that are unproven and possibly even toxic, mainly because Trump is arguably doing just that.

That was only the latest indication, though. Three weeks ago, for instance, President Trump was praising convalescent plasma, his administration having funneled $48 million into a program with the Mayo Clinic, allowing more than 53,000 Covid-19 patients to get plasma infusions. At the time, the same story reported that the FDA was preparing to issue an emergency use authorization for the plasma and that there was a lot of concern about there not being sufficient evidence to justify such a move:

The move would mean the F.D.A. is “yielding to political pressure,” said Dr. Luciana Borio, who oversaw public health preparedness for the National Security Council under Mr. Trump and who was acting chief scientist at the F.D.A. under President Barack Obama.

“I’m not as concerned about the political leaders having a misguided approach to science,” she said. “What I’m really concerned about is scientists having a misguided approach to science.”

On Monday, four former F.D.A. commissioners — including Dr. Scott Gottlieb, who served under Mr. Trump — called for more rigorous clinical trials to evaluate whether plasma is an effective treatment for the coronavirus. “If this is going to work, we need to do it right,” they wrote.

This effort should be coupled with serious studies to figure out whether and when plasma works. Thousands of covid-19 patients have been treated with plasma, but we are not much closer to definitively answering those questions. Its use makes common sense, and preliminary studies are promising, but we won’t know how to best use convalescent plasma products until we complete randomized clinical trials in which some people are treated and others receive usual care.

Consider the confusion surrounding the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for covid-19. Early studies without randomization gave contradictory results. We couldn’t tell if hydroxychloroquine had an effect or if differences in the mortality rates were due to something else.

Subsequent randomized trials showed no meaningful benefit and, in some trials, significant side effects and worse outcomes, enabling us to conclude hydroxychloroquine isn’t providing an advantage and allowing us to focus attention on more promising treatments.

Randomization might sound arbitrary, but we have only a limited supply of plasma, and we don’t yet know if it’s the plasma or something else that might make a patient better or worse. Maintaining clear and consistent standards for proving the safety and effectiveness of treatments will be critical in building trust in both treatments and an eventual vaccine.

The date this article was published was August 3.

So what do we know about the use of convalescent plasma versus COVID-19? Sadly, the answer is: Not much. We have some small case series, such as this one of five critically ill patients, all of whom recovered, but they’re not that useful other than as preliminary studies. We have a small randomized clinical trial of 103 patients in Wuhan, China with severe or life-threatening COVID-19, which was a negative trial. That’s not surprising, though, given that plasma therapy is usually less effective or actually ineffective in advanced, severe disease. The trial was also terminated early because the outbreak was contained and did not meet its accrual target of 200 subjects. There’s also a multicenter trial from Iran of 189 subjects, all COVID-19 positive patients, including 115 patients in the plasma therapy group and 74 patients in the control group that reported a decreased need for intubation in patients treated with plasma. However, it was not randomized, nor was it blinded.

It turns out that accrual has been a problem for the currently ongoing clinical trials as well, as described in this article in MedPage Today:

Recruitment into clinical trials, particularly in areas well past peak like New York, had slowed, and therapeutic hopes turned to treatments substantiated by data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), i.e., remdesivir and dexamethasone.

But more than 50,000 COVID-19 patients in the U.S. have been treated with the convalescent plasma via the FDA’s expanded access program — and researchers are so determined to get an evidence-based answer to whether this century-old treatment strategy works that they’re starting to pool their data.

But the unexpected demand for plasma has inadvertently undercut the research that could prove that it works. The only way to get convincing evidence is with a clinical trial that compares outcomes for patients who are randomly assigned to get the treatment with those who are given a placebo. Many patients and their doctors — knowing they could get the treatment under the government program — have been unwilling to join clinical trials that might provide them with a placebo instead of the plasma.

The trials have also been stymied by the waning of the virus outbreak in many cities, complicating researchers’ ability to recruit sick people. One of those clinical trials, at Columbia University, sputtered to a halt after the outbreak subsided in New York. One of its leaders, Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, looked for hospitals in other hot spots in the United States to continue the work. But he found few takers.

And:

As of last week, just 67 people had enrolled in the Columbia study — too few to form sound statistical conclusions. In a last-ditch effort, Dr. Lipkin’s team shipped the plasma to Brazil, where the epidemic is still raging.

Now, at the height of a public health crisis, the government’s push to distribute an unproven treatment to desperately ill patients as quickly as possible could come at the cost of completing clinical trials that would potentially benefit millions around the world by determining whether those treatments actually work.

Last week, as the FDA was on the verge of issuing an EUA, a group of top federal health officials, including Dr. Francis Collins and Dr. Anthony Fauci pushed back, arguing that the data for the use of convalescent plasma are currently too weak to justify an EUA. The result was that the EUA was put on hold, even though close to 100,000 patients had been treated with convalescent plasma, resulting in this outcome:

As of Monday, August 17, a nationwide program to treat Covid-19 patients with a fluid made from the blood of people who’d recovered from the disease—so-called convalescent plasma—had reached 97,319 patients.

That’s a huge number of people, considering that nobody really knows whether convalescent plasma actually works against Covid-19.

A spontaneously generated, self-assembling group of clinicians and cross-disciplinary researchers that built the nationwide program to ensure “expanded access” to convalescent plasma also created protocols for randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard for evidence in science. They hoped to test plasma’s ability to prevent disease after exposure, its capacity to treat Covid-19—and what Michael Joyner, an exercise physiologist at the Mayo Clinic who was instrumental in setting up the expanded-access network, called a “Hail Mary” protocol to try to help people who are severely ill, on ventilators.

The distribution system got approved and built; the trial protocols did not. They never began.

Unfortunately, this experience has not really helped. It hasn’t given us an answer. Let’s look at the preprint published two weeks ago by the Mayo Clinic group running the COVID-19 Expanded Access Program for convalescent plasma. Because it is a preprint, it has not been peer reviewed, nor is it randomized. It is retrospective, not prospective. It is open-label, not blinded. It did involve 2,807 acute care facilities in the US and its territories. Basically, this is the sort of thing that acupuncturists do; they base their belief in a treatment on inferior trial designs rather than randomized controlled clinical trials.

The trial itself examined 35,322 patients transfused with convalescent plasma. It included a high proportion of critically-ill patients, with 52.3% in the intensive care unit (ICU) and 27.5% receiving mechanical ventilation at the time of plasma transfusion. Seven-day mortality was 8.7% [95% CI 8.3%-9.2%] in the patients transfused within 3 days of their COVID-19 diagnosis but 11.9% [11.4%-12.2%] in the patients transfused 4 or more days after diagnosis (p<0.001). Similar findings were observed in 30-day mortality (21.6% vs. 26.7%, p<0.0001). So these were sick patients, and, to be honest, on an absolute basis these results are not that impressive. On the other hand, to be fair, we do use adjuvant chemotherapy that produces similarly small absolute increases in survival.

An aliquot of each plasma sample used to treat patients was saved, because at the time the study was begun there was no reliable way to measure the amount of anti-COVID antibodies. Binding antibody levels from the sera used were tested using the Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics VITROS Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) in accordance with manufacturer instructions. The Ortho-Clinical IgG CLIA is a qualitative assay based on a recombinant form of the SARS-CoV-2 spike subunit 1 protein. Plasma samples were divided into low, medium, and high levels of antibody. The finding was:

Importantly, a gradient of mortality was seen in relation to IgG antibody levels in the transfused plasma. For patients who received high IgG plasma (>18.45 S/Co), seven-day mortality was 8.9% (6.8%, 11.7%); for recipients of medium IgG plasma (4.62 to 18.45 S/Co) mortality was 11.6% (10.3%, 13.1%); and for recipients of low IgG plasma (<4.62 S/Co) mortality was 13.7% (11.1%, 16.8%) (p=0.048). This unadjusted dose-response relationship with IgG was also observed in thirty-day mortality (p=0.021). The pooled relative risk of mortality among patients transfused with high antibody level plasma units was 0.65 [0.47-0.92] for 7 days and 0.77 [0.63-0.94] for 30 days compared to low antibody level plasma units.

The authors used various methods to control for confounding and got similar results.

Having read the paper, I have to say, I’m getting a very “hydroxychloroquine” vibe from it. It’s a retrospective study for which the analyses were not pre-planned. There are a number of confounders that couldn’t be controlled for, in particular the reasons why a clinician might decide to treat a patient with convalescent plasma versus other therapies. Also, the analysis appears not to have been adjusted for study period, when outcomes might have been improving as doctors became better at managing COVID-19 patients, especially severely ill COVID-19 patients, or for periods after the publication of studies showing efficacy of remdesivir and the steroid dexamethasone. There are also a number of other major shortcomings that are catalogued in this post. Here’s the key point:

The part I don’t understand even from the Mayo paper is how they could say it is consistent with efficacy when it could also be consistent with the low titer units being unsafe. The Mayo study measured donor antibody levels in sera using the Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics VITROS Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG chemiluminescent immunoassay. This is qualitative assay based on a recombinant form of the SARS-CoV-2 spike subunit 1 protein. Results of this assay are based on the sample signal-to-cut-off (S/Co) ratio, with values <1.0 and ≥1.00 corresponding to negative and positive results . However, they created a “semi-quantitative” interpretation of this assay and established relative, low, medium and high binding antibody levels by setting thresholds for low and high based on the ~20th and ~80th percentiles of the distribution for the S/Co ratios, respectively. To us, a key issue to consider in this approach is that if their ‘low’ category included sub-therapeutic doses with non-neutralizing concentrations, rather than being removed from the pool of available plasma (as in our trial), these can theoretically trigger antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) which can facilitate virus uptake and subsequent worsening of symptoms. For this reason, doesn’t it seem the group receiving ‘low’ titer plasma could have actually been made WORSE, causing the ‘high’ group to look relatively efficacious and fostering an erroneous interpretation of the results???

Without a real control group, you can’t rule out this possibility with observational evidence. The same post also notes that many of the names of FDA officials were redacted from the EUA announcement. I’ve never seen anything like this before, and the redaction of the names of people involved in evaluating the science is very suspicious to me.

Basically, this isn’t very impressive evidence. Sure, it works as preliminary data to justify an RCT, but it doesn’t show that convalescent plasma works. I also totally agree with this sentiment:

The authors provided a list of reasons why it was not possible to randomize patients to CP from the start. These reasons are singularly unconvincing.

Indeed they are.

Politics versus science in COVID-19

The story of convalescent plasma as a treatment for COVID-19 is a story of how, as was the case for hydroxychloroquine, politics interfered in the ability of doctors and scientists to determine if a treatment actually works. The bottom line right now is well described by a Cochrane “living systematic review” that, as of yesterday, was concluding:

We are very uncertain whether convalescent plasma is beneficial for people admitted to hospital with COVID-19. For safety outcomes we also included non-controlled NRSIs. There was limited information regarding adverse events. Of the controlled studies, none reported on this outcome in the control group. There is only very low-certainty evidence for safety of convalescent plasma for COVID-19. While major efforts to conduct research on COVID-19 are being made, problems with recruiting the anticipated number of participants into these studies are conceivable. The early termination of the first RCT investigating convalescent plasma, and the multitude of studies registered in the past months illustrate this. It is therefore necessary to critically assess the design of these registered studies, and well-designed studies should be prioritised.

This was last updated in June, and I’m afraid that the Mayo Clinic experience doesn’t change that conclusion, and I agree with this sentiment:

Here’s another perspective, using the more up-to-date number: “In my mind, treating 98,000 people with plasma and not having conclusive data if it worked is problematic, and we should have a more robust data set before we give 98,000 people a product,” says John Beigel, associate director for clinical research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

Yet that’s exactly what we’ve done, and that’s what we’re going to be doing a lot more of now that the President has announced the FDA’s EUA for convalescent plasma. Yes, it’s true that EUAs include language saying that the EUA is “not intended to replace randomized clinical trials and facilitating the enrollment of patients into any of the ongoing randomized clinical trials is critically important for the definitive demonstration of safety and efficacy” and that the FDA “continues to recommend that the designs of ongoing randomized clinical trials of COVID-19 convalescent plasma and other therapeutic agents remain unaltered, as COVID-19 convalescent plasma does not yet represent a new standard of care based on the current available evidence”. It included the same sort of language in the EUA for hydroxychloroquine. It didn’t matter. People (and too many doctors) still view an EUA as close enough to the same thing as FDA approval for the two to be a distinction without a functional difference

Particularly irritating to me was this nauseatingly sycophantic statement by Alex Azar, Health and Human Services Secretary, included in the actual EUA announcement by the FDA – something I’ve never seen before in an EUA by the FDA:

“The FDA’s emergency authorization for convalescent plasma is a milestone achievement in President Trump’s efforts to save lives from COVID-19,” said Secretary Azar. “The Trump Administration recognized the potential of convalescent plasma early on. Months ago, the FDA, BARDA, and private partners began work on making this product available across the country while continuing to evaluate data through clinical trials. Our work on convalescent plasma has delivered broader access to the product than is available in any other country and reached more than 70,000 American patients so far. We are deeply grateful to Americans who have already donated and encourage individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 to consider donating convalescent plasma.”

Seeing what’s happened during the pandemic, I’m reminded what I wrote about the Trump administration very early in its time. Even just 80 days in, I saw signs of weakening the FDA’s ability to make sure that drugs are only approved based on the strongest scientific evidence, while more recently I saw even more alarming signs of the same problem. When the cruel sham of “right-to-try” was passed into law in 2018, that pretty much sealed my fear that the FDA is becoming totally politicized, and I wasn’t surprised that the law is failing. The pandemic just provided the pretext for the final assault on the FDA as a reliable arbiter of which drugs should be approved based on actual scientific evidence, rather than fairy dust, wishful thinking, and the political imperative of a President known for promoting snake oil.