As I sat down to write today’s post, I realized that it would be hard to write about anything other than the coronavirus pandemic, given that last week was the week that, as they say, “shit got real” and the news is about little else. This is not the sort of post that I normally do, given that it’s more straight “medical blogging” than we usually do here at SBM, but it’s the sort of post that I, as editor, think that we need to write. Even though Steve did a great post a couple of weeks ago on coronavirus, events have been moving so rapidly that an update is definitely indicated. I write this realizing that, given how fast events are progressing, this post could be obsolete in just a week or two.

Of course, things got bad at least a couple of weeks ago in Italy (and several weeks before that in China), where in Lombardy hospitals and intensive care units are now so completely overwhelmed that the Italian College of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) wrote a remarkable set of guidelines stating that, in essence, wartime triage has become necessary because there are simply too many patients for all of them to receive adequate medical care. To give you an idea, over the weekend Italy reported its highest single-day death toll from COVID-19 (368), bringing its death toll to 1,809 deaths. Multiple European nations are following Italy’s lead in closing their borders, and France ordered all “non-indispensable” businesses closed, including restaurants, bars and movie theaters. It’s not alone. [NOTE added later: Monday morning, Michigan shut down all bars and restaurants except for carryout and delivery.]

Meanwhile, Seattle is under strain and suffering staffing shortages as its hospitals groan under the burden of COVID-19 patients, and it likely won’t be long before parts of the US resemble Lombardy, the wealthy area of Italy that’s been hardest hit. Meanwhile, panic buying of toilet paper (among other things) has spread throughout the entire US. (Indeed, I went to CVS on Saturday to pick up my blood pressure medicine prescription, and the store was totally cleaned out of ibuprofen, of all things.) It won’t be long before other parts of the US follow.

Elsewhere, in New Jersey Hoboken imposed a citywide 10 PM curfew and closed all of its bars, while Teaneck imposed self-quarantine on its residents. Friday, unable to deny the severity of the crisis any more, President Donald Trump finally declared a national state of emergency on Friday afternoon. In my own state, the governor ordered all schools closed at least until April 5; my university extended spring break a week in order to give faculty time to make the rest of their courses this term online-only; Henry Ford Hospital and its satellites are making contingency plans to set up tents to screen people before they enter the hospital and triage potential coronavirus patients; Detroit-area hospitals and nursing homes have imposed strict visitor restrictions. The list goes on. As I said, last week was the week when shit got real in the US. So let’s get into it.

What are coronaviruses and COVID-19?

Coronaviruses are a genus of viruses that can infect humans and animals. In humans, coronaviruses can cause the “common cold” (the common cold is actually caused by a number of different viruses, but coronavirus strains cause around one-quarter) but certain strains can cause severe disease in humans. For instance, there was an epidemic of SARS (severe acute respiratory distress syndrome), which was caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV) that started in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002 and went on to involve 26 countries, infect over 8,000 people, and result in nearly 800 deaths between 2002 and 2003. (I remember that the American Association for Cancer Research meeting in April 2003 was canceled and rescheduled for July.) Even more deadly was the MERS (Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, caused by MERS-CoV) outbreak, which originated in Saudi Arabia and resulted in 1,000 cases and over 400 deaths from 2012-2015. SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 belong to the betacoronavirus subtype.

The first cases of disease in the current pandemic were reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Just a word on nomenclature, the new strain of coronavirus responsible for the pandemic has been named SARS-CoV-2, and the disease it causes “coronavirus disease 2019” (abbreviated “COVID-19”). According to the CDC, COVID-19 has been detected in more than 100 locations internationally, and on January 30, 2020, the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee of the WHO declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern.” On March 11, the WHO officially declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic, and, as I mentioned above, on March 13, President Trump declared a national emergency in response.

How does SARS-CoV-2 spread?

The first cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China were thought to have arisen due to spread of this novel coronavirus from animal to human. Currently, it’s thought that SARS-CoV-2 arose in bats and made the jump to humans through an intermediary species in the Wuhan markets. That “other species” is still not clear, although it is suspected that the intermediary might have been pangolins, which are popular in traditional Chinese medicine. (No, contrary to a conspiracy theory popular now, SARS-CoV-2 is not an escaped bioweapon that came from a failed attempt to develop a vaccine to the 2002-2003 SARS.)

Of course, now person-to-person transmission is the main way that COVID-19 is spread. People with the disease cough or sneeze, spreading respiratory droplets, which can land either in another person’s nose or mouth or on nearby objects, which other people can touch. When those people then touch their face, nose, mouth, or eyes, the disease infects them. Usually, symptoms start with a cough and fever, but in a minority of those infected the virus infects the lungs, leading to severe disease.

That’s why hand washing and trying very hard not to touch your face is so important. And I don’t mean the half-assed hand washing that we all sometimes do when we’re in a hurry, but rather a good solid hand washing with soap and water scrubbing all surfaces for at least 20-30 seconds. Hand sanitizers with at least 60% alcohol work too, but not as well as hand washing. Basically, wash your hands after touching anything that might harbor the virus. It’s also not a bad idea to carry around disposable paper towels to use open when opening doors and pushing elevator buttons and the like.

Regular facemasks are not very effective and only recommended by the WHO if you are taking care of someone with a known or suspected case of COVID-19 or if you’re coughing yourself, to avoid infecting others. The much more stringent N95 respirators are recommended only for health care personnel during procedures and contact that generate respiratory droplets, and I note that such respirators must be fit-tested to be effective. Unfortunately, there’s been a run on masks, both regular and N95 respirators, leading to shortages for health care personnel who need them.

Finally, social distancing is an important strategy to prevent infection (more on that later).

Why is COVID-19 so concerning?

COVID-19 symptoms can range from asymptomatic to severe pneumonia leading to organ failure and death. COVID-19 in most people is mild and resembles the common cold. According to the WHO, symptoms include fever (87.9%), dry cough (67.7%), fatigue (38.1%), sputum production (33.4%), shortness of breath (18.6%), sore throat (13.9%), headache (13.6%), muscle or joint aches (14.8%), chills (11.4%), nausea or vomiting (5.0%), nasal congestion (4.8%), diarrhea (3.7%), coughing up blood (0.9%), and conjunctival congestion (0.8%). Symptoms generally occur an average of 5-6 days after infection, but the range is from one to 14 days.

Now here’s the reason the prospect of COVID-19 spreading through the population is so concerning. Quoting the WHO report:

Most people infected with COVID-19 virus have mild disease and recover. Approximately 80% of laboratory confirmed patients have had mild to moderate disease, which includes non-pneumonia and pneumonia cases, 13.8% have severe disease (dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥30/minute, blood oxygen saturation ≤93%, PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300, and/or lung infiltrates >50% of the lung field within 24-48 hours) and 6.1% are critical (respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction/failure). Asymptomatic infection has been reported, but the majority of the relatively rare cases who are asymptomatic on the date of identification/report went on to develop disease. The proportion of truly asymptomatic infections is unclear but appears to be relatively rare and does not appear to be a major driver of transmission.

Dyspnea means shortness of breath, and a respiratory frequency of greater than 30 breaths/minute is very alarming (a normal respiratory rate is between 12-20 breaths/minute), and an O2 saturation of <93% on room air in someone who was previously healthy is not good. As for lung infiltrates on chest X-ray, when disease is severe, SARS-CoV-2 causes bilateral diffuse lung infiltrates. An infiltrate is nothing more than a substance denser than air that shows up as white blotches on chest X-ray. In the lungs, such infiltrates usually mean fluid, inflammation, or pus. Here’s what they look like:

Here’s what a normal chest x-ray looks like:

You get the idea. Let’s just say that such infiltrates result in impaired oxygen exchange. In any case, this pneumonia can set off a cascade of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ dysfunction, which, when it happens, has a high mortality.

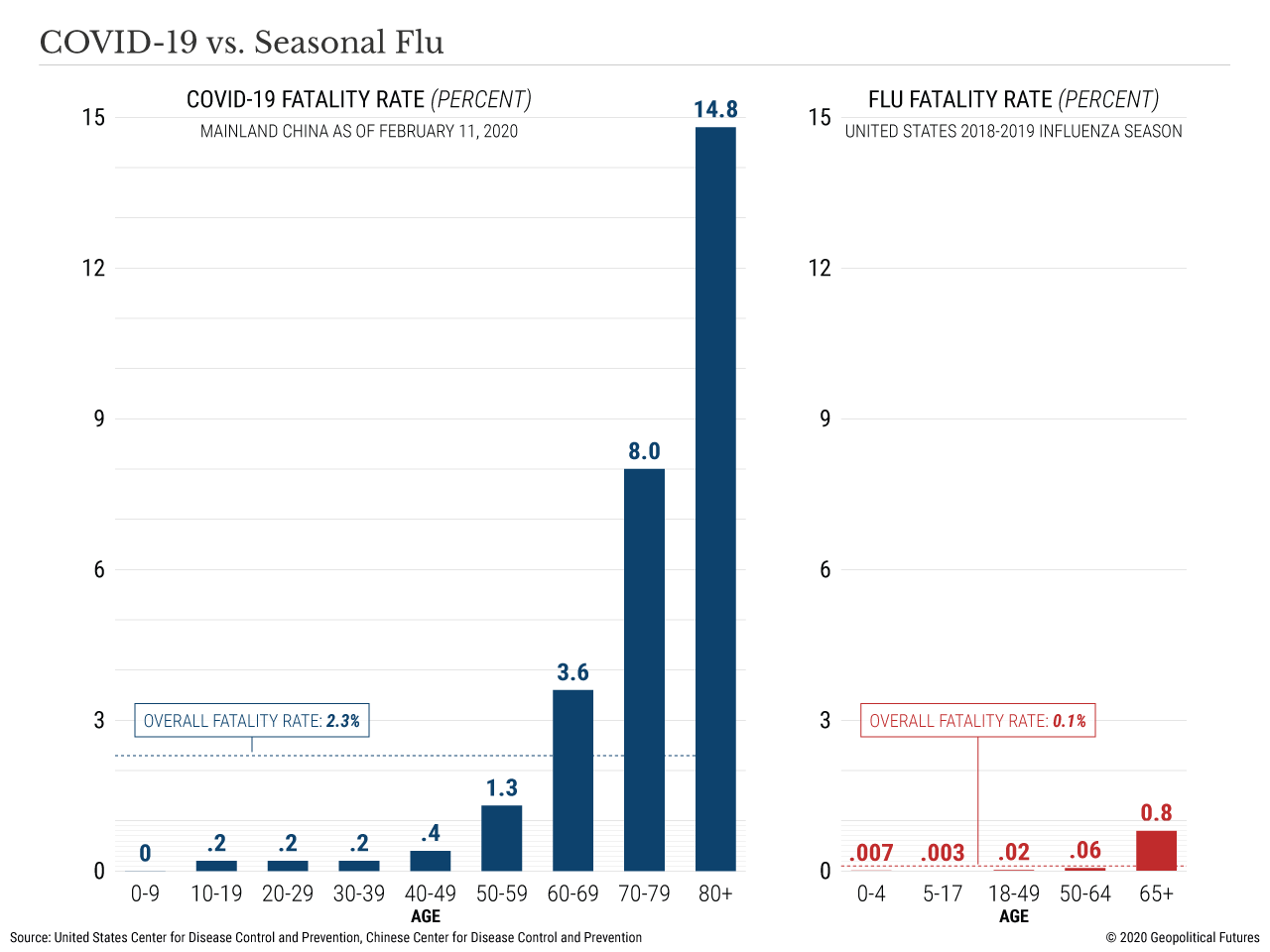

Understandably, what everyone worries about is simple: What are my odds of dying if I get COVID-19? (And a lot of us are going to get it.) The answer, of course, is: It depends. Last week the CDC estimated the case fatality rate for COVID-19 (the percent of patients with confirmed disease who die) to from 0.25%-3.0%. That’s all comers. Why the uncertainty? Compared to the likely prevalence of COVID-19, not very many people have been tested, particularly in the US, where, in my not-so-humble opinion (and not just me), testing has been criminally botched. In calculating case fatality rates, the denominator is the number of people with the disease, and we just don’t have a good handle on that yet, meaning that these estimates are likely too high. Even so, the lowest estimates (around 0.7%) are at least five to seven times higher than the case fatality rates for seasonal influenza (0.1%), and the highest CDC-estimated rate is around 30 times more deadly than the flu.

There’s a wrinkle, though. Although it’s true that we could be overestimating case fatality rates because of asymptomatic transmission and an unknown number of asymptomatic cases artificially lowering the denominator, we could also be underestimating the case fatality rate. Correspondence published last week in The Lancet Infectious Diseases noted:

As of March 1, 2020, 79,968 patients in China and 7,169 outside of China had tested positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 Among Chinese patients, 2873 deaths had occurred, equivalent to a mortality rate of 3.6% (95% CI 3.5–3.7), while 104 deaths from COVID-19 had been reported outside of China (1·5% [1.2–1.7]). However, these mortality rate estimates are based on the number of deaths relative to the number of confirmed cases of infection, which is not representative of the actual death rate; patients who die on any given day were infected much earlier, and thus the denominator of the mortality rate should be the total number of patients infected at the same time as those who died. Notably, the full denominator remains unknown because asymptomatic cases or patients with very mild symptoms might not be tested and will not be identified. Such cases therefore cannot be included in the estimation of actual mortality rates, since actual estimates pertain to clinically apparent COVID-19 cases.

And:

We re-estimated mortality rates by dividing the number of deaths on a given day by the number of patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection 14 days before. On this basis, using WHO data on the cumulative number of deaths to March 1, 2020, mortality rates would be 5·6% (95% CI 5.4–5.8) for China and 15.2% (12·5–17·9) outside of China. Global mortality rates over time using a 14-day delay estimate are shown in the figure, with a curve that levels off to a rate of 5.7% (5·5–5·9), converging with the current WHO estimates. Estimates will increase if a longer delay between onset of illness and death is considered. A recent time-delay adjusted estimation indicates that mortality rate of COVID-19 could be as high as 20% in Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak.6 These findings show that the current figures might underestimate the potential threat of COVID-19 in symptomatic patients.

So which is it, 0.25%-3.0% or around 5.7%? Or is it something different, such as reported here, where estimates range from 3.9% in China to 2.4% for the rest of the world? The answer is: We don’t know yet, because we don’t know how many people have been infected and how many of those are asymptomatic. It is, however, very likely that symptomatic patients will have a higher case fatality rate, but there isn’t anything particularly striking in that observation because asymptomatic patients are highly unlikely to die of COVID-19. Suffice to say that, right now, estimates for case fatality rates are all over the map between around 0.5% and 6.0%. Over time, estimates will likely converge on a more reliable rate. There’s a caveat, though. It’s important to remember that case fatality rates are context-specific, changing with time and location. There is no single case fatality rate for a disease. We also need to be very careful interpreting case fatality rate estimates during the middle of an outbreak or pandemic. Many are currently infected, and we don’t yet know which ones will recover or die—or even accurately which ones are infected.

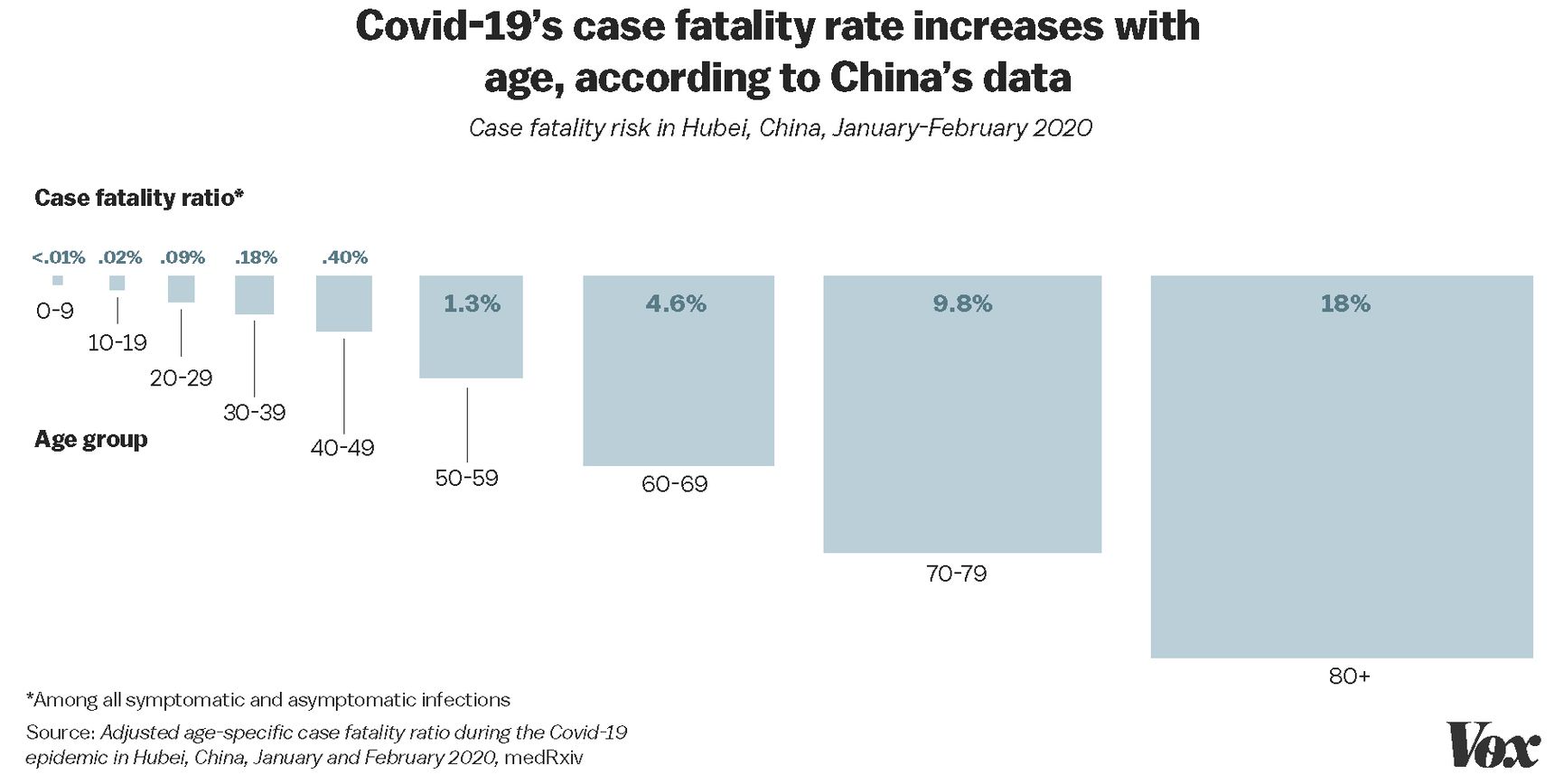

Again, though, this is for all comers. If there’s one thing we know thus far, it’s that COVID-19 appears to be much less serious in children and that it’s much deadlier for the elderly. For instance, in China, there were no reported deaths in children 9 years old and under, but the case fatality rate in adults over 80 was high. Here is a graph from Vox:

Here are data from China comparing COVID-19 to seasonal influenza:

Here are data from Italy:

3. Some data from the Lombardy #Covid19 outbreak — like elsewhere, almost no deaths under age 50. pic.twitter.com/AQxtz4PztC

— Helen Branswell 🇨🇦 (@HelenBranswell) March 13, 2020

The median age for those who died was 64:

5. More data from Cecconi’s #Covid19 presentation through #JAMALive. pic.twitter.com/OFvxW0O9j8

— Helen Branswell (@HelenBranswell) March 13, 2020

And here’s a useful comparison:

Case fatality rate of COVID-19 vs 1918 flu vs seasonal flu as a function of age. COVID-19 is worse than seasonal flu but doesn’t seem to have the mortality peaks for young children and young adults that were seen in 1918 flu. https://t.co/o3961J3Nle pic.twitter.com/j2WeURchUT

— Claus Wilke (@ClausWilke) March 2, 2020

No matter what the “true” case fatality rates turn out to be, there is no denying that COVID-19 is much deadlier if you’re over 60 and alarmingly deadly for those over 80.

Flattening the curve

There’s more to worry about than case fatality rates, though. As noted above, roughly 20% of those with COVID-19 will develop disease severe enough to require hospitalization, with roughly 5-6% requiring mechanical ventilation. Given those numbers, it wouldn’t take very many cases relative to the total population to completely overwhelm our medical system. This has already happened in Italy, as I mentioned early on, to the point where Italian doctors have little choice but to institute wartime-like triage, and, again, Lombardy is a wealthy region with excellent medical facilities. It’s no wonder that, in the light of what we’re seeing in other parts of the world, doctors and public health officials are becoming very alarmed, with good reason.

Here’s where social distancing and the concept of “flattening the curve” comes in. Social distancing involves avoiding close contact with other people, preferably maintaining a six foot distance whenever possible. It is to promote social distancing that so many colleges have closed classes down in favor of online-only learning; so many schools have closed; NCAA March Madness is canceled; the baseball season put on indefinite hold; the basketball and hockey seasons prematurely has ended; so many professional conferences have been canceled or postponed; and so many universities and companies have banned business travel. It’s why Italy has closed all businesses except for the most essential, such as grocery stores and drug stores. It’s why Hoboken closed all of its bars, restaurants, daycares, movie theaters, gyms, and playgrounds.

How does this work? First, you have to understand that at this point we can’t prevent SARS-CoV-2 from spreading. It’s far, far too late for that. (The horse has left the proverbial barn, so to speak.) The virus is out and has been in the US several weeks at least. The strategy now is therefore to slow its spread as much as possible, the idea being, even if the total number of cases ends up being the same (although we do want to lower the total number of cases as much as possible and social distancing can achieve that), to keep the peak number of new cases per day/week/month as low as possible, hopefully low enough that COVID-19 cases don’t completely overwhelm our healthcare system and ICU bed capacity. When our hospital and ICU bed capacity is overwhelmed, more people die of coronavirus. However, more people also die of other causes due to delays in treatment when healthcare resources are unavailable due to being tied up caring for coronavirus patients.

You might have seen this graph, or one like it, on social media. It explains visually what I was trying to explain verbally:

Our #FlattenTheCurve graphic is now up on @Wikipedia with proper attribution & a CC-BY-SA licence. Please share far & wide and translate it into any language you can! Details in the thread below. #Covid_19 #COVID2019 #COVID19 #coronavirus Thanks to @XTOTL & @TheSpinoffTV pic.twitter.com/BQop7yWu1Q

— Dr Siouxsie Wiles (@SiouxsieW) March 10, 2020

Here is another version of the curve:

Of course, the peak of the lower curve could well brush up against or surpass the medical system’s capacity. Likely it will do just that in some parts of the country. Even so, that would be far more manageable than a scenario like the high peak number of cases, because the capacity of the healthcare system would be surpassed by much less.

Will it be enough? I don’t know. I have my doubts because of some Tweets I saw over the weekend. Here was Dublin on Saturday night:

Just sent to me from Temple bar.

Glad we are taking this serious.#COVIDー19 #CloseThePubs pic.twitter.com/YI1YOwzDV7

— Gareth Neary (@Tiananmens) March 14, 2020

And here was Chicago:

Just drove through Wrigleyville. Every bar on Clark Street has a long line of people ingreen regalia waiting to get drunk and spread a virus. pic.twitter.com/m28q5SnF3J

— Unlike web sites of the past. (@spiderstumbled) March 14, 2020

Elsewhere:

We are doomed pic.twitter.com/EpIXKo84IH

— Barstool Sports (@barstoolsports) March 15, 2020

Then there were utterly brain dead Tweets like this:

The fear is far worse than the virus. The governments have it wrong. Stay open for business. If not, so many more people will die from a crashing economy than from this virus. #corona #dustbowl #food #clothing #shelter

— Tim Draper (@TimDraper) March 14, 2020

And this:

I fear more draconian measures will soon be necessary in the US, measures similar to those in Italy. In fact, they’re arguably necessary now. We have the luxury of being a couple of weeks behind Europe in terms of the progress of the pandemic within our borders.

And then there are articles like this one by Heather Mac Donald on New Criterion, which uses “whataboutism” to downplay the potential severity of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Much has been made of the “exponential” rate of infection in European and Asian countries—as if the spread of all transmittable diseases did not develop along geometric, as opposed to arithmetic, growth patterns. What actually matters is whether or not the growing “pandemic” overwhelms our ability to ensure the well-being of U.S. residents with efficiency and precision. But fear of the disease, and not the disease itself, has already spoiled that for us. Even if my odds of dying from coronavirus should suddenly jump ten-thousand-fold, from the current rate of .000012 percent across the U.S. population all the way up to .12 percent, I’d happily take those odds over the destruction being wrought on the U.S. and global economy from this unbridled panic.

Her comparison of deaths due to automobile collisions elsewhere in the article is a particularly silly bit of whataboutism. Automobile collisions are not contagious, and we already do a lot of things to decrease the death rates, from requiring safety harnesses and airbags to improving highway and road design. Moreover, in the article, she also basically dismisses concerns about how hard COVID-19 hits the elderly because they don’t have much longer to live anyway. (Read it for yourself if you think I’m being unfair.) In any event, Ms. Mac Donald’s fear quotes around the word “pandemic” aside, her bit about whether the pandemic “overwhelms our ability to ensure the well-being of U.S. residents with efficiency and precision” is exactly the reason social distancing measures instituted early are so important, to prevent our health care system from being overwhelmed. Let’s put it another way. It’s estimated that, under a worst-case scenario, as many as three million in the US could require ventilation:

The maximum number of ventilators that could be put in the field in the United States is about 160,000. So under those scenarios, there would theoretically be enough capacity to meet the need.

But if the coronavirus outbreak gets worse, we could quickly run out. In a situation more similar to the Spanish flu pandemic (675,000 dead in the US), about 742,500 people in the United States would require ventilation, according to government estimates. We don’t have that many.

The health system is much more than ventilators, of course, and the concerns about capacity apply to the rest of it, too. As HuffPost’s Jonathan Cohn reported, US hospitals have about 45,000 beds in their intensive care units. In a moderate outbreak, about 200,000 patients may need to be put in the ICU, but under a more severe outbreak, it could be nearly 3 million.

That number can be drastically lowered through social distancing interventions. Moreover, acting early is far more effective at flattening the curve than acting late, as infectious disease epidemiologist Britta Jewel showed in a thought experiment in which she modeled the exponential growth of the number of COVID-19 cases:

She explains:

The graph illustrates the results of a thought experiment. It assumes constant 30 percent growth throughout the next month in an epidemic like the one in the U.S. right now, and compares the results of stopping one infection today — by actions such as shifting to online classes, canceling of large events and imposing travel restrictions — versus taking the same action one week from today.

The difference is stark. If you act today, you will have averted four times as many infections in the next month: roughly 2,400 averted infections, versus just 600 if you wait one week. That’s the power of averting just one infection, and obviously we would like to avert more than one.

The principle is that, with the exponential growth phase of an epidemic, individual and institutional actions such as social distancing taken early on can have a much greater impact than if the same actions are taken even a week later.

If you want another way to visualize how to “flatten the curve”, check out this simulator.

Ironically, to protect our population and our health care system is why we’re doing these things. Arguably, it might well be too little, too late. Only time will tell. Remember these words from Michael Levitt, former Secretary of Health and Human Services, “Everything we do before a pandemic will seem alarmist. Everything we do after a pandemic will seem inadequate.”

I really hope that, when this is all over, our actions today seem alarmist. I fear that they won’t, though. To show why, just look at this Tweet with graphs showing how accurate projections were for the number of cases and number of ICU patients in Italy:

Striking @TheLancet data on Italy’s increase in #COVID19 cases. I adapted their figure with today’s count: they are spot on. From 2,000 to 20,000 in 2 weeks (10X increase). Likewise expected rise in ICU pts. US government: #ActNow #SaveLives #CancelEverything #SocialDistancing pic.twitter.com/nGE8JocmuD

— Mark Drazner (@MarkDrazner) March 15, 2020

And if you really want to be alarmed, the worst case scenario modeled by the CDC for the US suggest as many as 214 million infected and 1.7 million dead.

Make no mistake. SARS-CoV-2 is in the US, and we are currently at the early end of these curves. The only question how robust the exponential phase of growth of the number of cases will be and whether we can successfully flatten the curve

Quackery and conspiracy theories

Unsurprisingly, whenever there are outbreaks or new pandemics, there are quacks. There is another time and place when I might write about them, such as the claim that SARS-CoV-2 is a bioweapon that escaped or the result of an attempt at a SARS vaccine gone wrong or that the flu vaccine increases susceptibility to COVID-19 (there’s no evidence that it does). There are also quacks galore recommending everything from homeopathy to colloidal silver to supplements to Hulda Clark’s zapper to chiropractic to prevent or treat COVID-19. It’s so bad that my local police department just emailed a notice to residents to beware of COVID-19 scams. I’m sure there will be plenty to write about in the coming months. And, make no mistake; this pandemic is not going to be over as quickly as many seem to think. It will last months, not weeks. It’s very difficult to predict, but not in the two- or three-week timeframes of current social distancing measures. They will very likely need to be extended much longer. On Meet the Press yesterday, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, warned that US citizens would have to make personal sacrifices and comply with government guidelines to avoid a “worst-case scenario” and said, “Americans should be prepared that they are going to have to hunker down significantly more than we as a country are doing.”

So, until I (and others here) get a chance to write about more of these scams than the handful we’ve touched upon, be careful out there. Stay home as much as possible. (That goes double if you’re over 60, triple if you’re 80 or older.) Don’t fly if you can avoid it. Try not to touch your face. (Much easier said than done, as I’ve discovered.) If you can work from home, do so. Avoid unnecessary contact with strangers as much as you can. If you start developing symptoms, contact your doctor for instructions. If you test positive for SARS-CoV-2, self-quarantine as instructed unless you start to develop shortness of breath and need to go to the emergency room.

And, above all else, wash your stinking paws, you damned dirty apes!