A few years ago I looked at the burgeoning market for direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing that was being rolled out in pharmacies. Pharmacogenomics, as it’s called, is claimed to provide valuable information that can help in prescription drug selection. And it’s true that over 100 drugs are approved by the FDA that reference genetic variation in response. At the time of my original post, I commented that genomics was promising, but that its overall effectiveness had yet to be proven. Fast forward to 2018, and the FDA has now announced that the company 23andme has had a DTC genetic test approved for detecting variations in how certain medications may behave in your body. Has the science caught up to the marketing and hype?

What did the FDA approve?

The FDA made the following announcement:

Today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration permitted marketing, with special controls, of the 23andMe Personal Genome Service Pharmacogenetic Reports test as a direct-to-consumer test for providing information about genetic variants that may be associated with a patient’s ability to metabolize some medications to help inform discussions with a health care provider. The FDA is authorizing the test to detect 33 variants for multiple genes.

It sounds promising, but the FDA is very limited in endorsing the test itself:

The 23andMe Personal Genome Service Pharmacogenetic Reports test is not intended to provide information on a patient’s ability to respond to any specific medication. The test does not describe an association between the detected variants and any specific drug nor whether a person will or will not respond to a particular drug. Furthermore, health care providers should not use the test to make any treatment decisions. Results from this test should be confirmed with independent pharmacogenetic testing before making any medical decisions.

This seems hardly like a ringing endorsement of DTC testing. It also notes:

The FDA’s review of the test determined, among other things, that the company provided data to show that the test is accurate (i.e., can correctly identify the genetic variants in saliva samples) and that it can provide reproducible results. The company submitted data on user comprehension studies that demonstrated that the test instructions and reports were understood by consumers. The test report provides information describing what the results might mean, what the test does not do and how to interpret results.

Reading between the lines, my sense is that the FDA seems to simultaneously feel it’s reasonable to make this information available, while simultaneously cautioning that actual medical decisions, including using it to select or adjust medications, is not appropriate without confirmatory testing. Which seems like a pretty weak endorsement for sales. Interestingly, the FDA issued a warning about unapproved tests the following day, on November 1, 2018:

The FDA has become aware of genetic tests with claims to predict how a person will respond to specific medications in cases where the relationship between genetic (DNA) variations and the medication’s effects has not been determined. These genetic tests might be offered through health care providers or advertised directly to consumers and claim to provide information on how a patient will respond to medications used to treat conditions such as, depression, heart conditions, acid reflux, and others. They might claim to predict which medication should be used or that a specific medication may be less effective or have an increased chance of side effects compared to other medications due to genetic variations. Results from these tests may also indicate that the health care provider can or should change a patient’s medication based on results from these tests. The FDA is also aware of software programs that interpret genetic information from a separate source that claim to provide this same type of information. However, sufficient clinical evidence is not currently available for these genetic tests or software programs and, therefore, these claims are not supported for most medications.

It continued:

There are a limited number of cases for which at least some evidence does exist to support a correlation between a genetic variant and drug levels within the body, and this is described in the labeling of FDA cleared or approved genetic tests and FDA approved medications. The FDA authorized labels for these medical products may provide general information on how DNA variations may impact the levels of a medication in a person’s body, or they may describe how genetic information can be used in determining therapeutic treatment, depending on the available evidence.

The bottom line from the FDA seems to be, if the correlation between test result and drug effect isn’t already in the product’s marketing and use information, then the result should not be considered useful for clinical decision-making. The FDA gives that warning to manufacturers in the same warning:

If your test claims to predict a patient’s response to specific medications, confirm that the FDA-approved drug labels for medications included in your test labeling describe how genetic information can be used in determining therapeutic treatment.

Hype vs. science

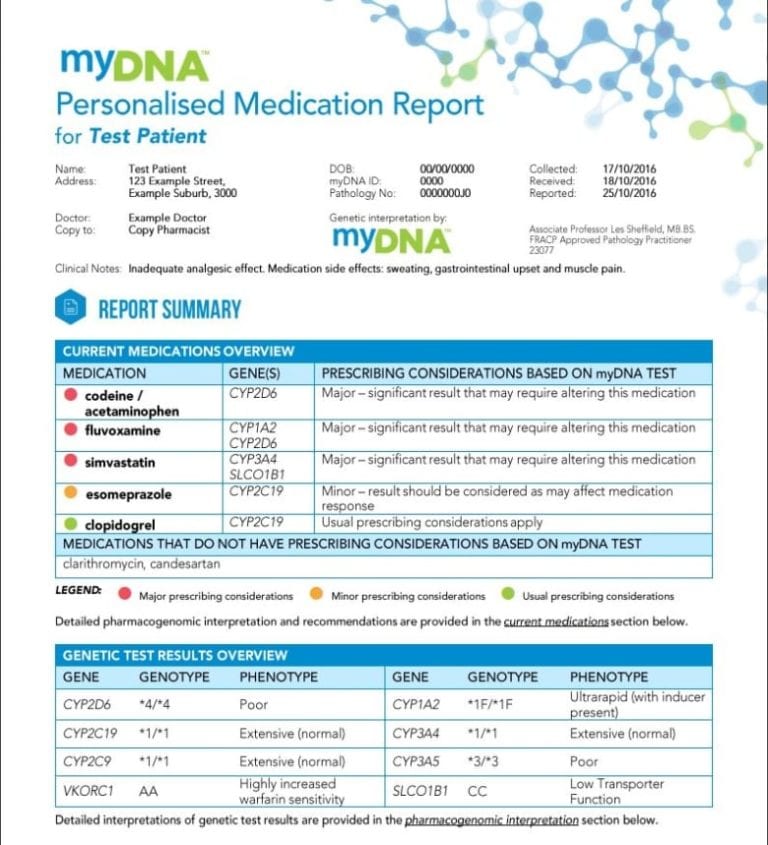

When genetic testing gives results that have not been show to be definitively useful, then problems can occur. Changing or avoiding drugs based on unvalidated testing has the potential to worsen your care, not improve it. For example, numerous tests claim to give results which can help in antidepressant selection. However the relationship between genetic tests and the effectiveness of antidepressants has not been proven. Yet that’s exactly what the myDNA test does, as noted in a report by the CBC:

The CBC report on DTC testing is cautiously positive, profiling a pharmacy that sells the test, but also sharing some criticisms and concerns, including pointing to a statement from the Canadian Medical Association that cautions physicians about DTC genetic testing:

DTC genetic tests are not regulated in Canada. The clinical validity and reliability of these tests varies widely, but DTC genetic testing companies make them available to consumers without distinguishing between those that may be useful to the management of one’s health, those that have some limited health value, and those that are meant purely for recreational use.

It continues,

The CMA believes that patients have the right to be fully informed about what a DTC genetic test can and cannot say about their health and that the scientific evidence on which a test is based should be clearly stated and easy to understand.

The 23andme test is the only pharmacogenomic test approved by the FDA. None are approved in Canada at all. A paper published in March 2018 by Stefany Tandy-Connors and colleagues, entitled “False-positive results released by direct-to-consumer genetic tests highlight the importance of clinical confirmation testing for appropriate patient care” highlights some of the quality concerns with DTC test. The researchers looked at 49 patient samples where DTC testing had identified genetic variants. They reported:

Our analyses indicated that 40% of variants in a variety of genes reported in DTC raw data were false positives. In addition, some variants designated with the “increased risk” classification in DTC raw data or by a third-party interpretation service were classified as benign at Ambry Genetics as well as several other clinical laboratories, and are noted to be common variants in publicly available population frequency databases.

Purchasing a test? Proceed with caution

DTC genetic testing is promising but, like many new medical technologies, the hype is outpacing the actual science, as the relevance of these tests, even when they are accurate, is often unclear. While the marketing paints an optimistic picture of how these tests may be useful, the opposite is equally likely to be the case. The FDA’s regulation and approval of the 23andme test is a cautious first step in regulating this “wild west” of healthcare.