Photo via CFI.

In 2018, the Center for Inquiry (CFI) filed a lawsuit on behalf of the general public against US pharmacy chain CVS for selling homeopathy. In 2019, it filed a similar lawsuit against Walmart, alleging fraud through their sale of these products. Both lawsuits were filed under the District of Columbia’s Consumer Protections Procedures Act (CPPA), which “establishes an enforceable right to truthful information from merchants about consumer goods and services that are or would be purchased, leased, or received in the District of Columbia”. Importantly, as Jann Bellamy noted when she blogged about these lawsuits at the time, the CPPA does not require proof that any consumers were actually mislead, deceived or damaged.

Both lawsuits were initially dismissed. Last week, in a unanimous ruling the District of Columbia Court of Appeals overturned both dismissals. The lawsuits will proceed.

Dilutions of Grandeur: The myth of homeopathy

Among all the forms of alternative medicine, homeopathy is possibly the most implausible of them all. Samuel Hahnemann invented the practice of homeopathy in the early 1800s. While the practice of medicine slowly progressed to a scientific model based on objective observations, homeopathy, on the other hand, has never progressed or evolved. Its practices today are frozen in the same prescientific beliefs of Hahnemann. Homeopathy is based on the idea that “like cures like”, in that a small dose of what causes a symptom can actually cure that symptom. Like-cures-like is simply sympathetic magic, a pre-scientific belief, and is the entire basis for homeopathy:

- Like-cures-like: in homeopathy, a substance that is believed to cause a symptom, is diluted to treat that same symptom. Any substance is thought to be an effective remedy if it’s diluted enough: cancer, boar testicles, crude oil, oxygen, skim milk, even vacuum cleaner dust or moonlight can be (and is) a homeopathic remedy. Deciding which substances will cure which symptoms is determined by a process called a “proving” which is equally without any scientific basis. (See the homeopathic “provings” for the Berlin Wall remedy and sunlight reflected off the planet Saturn, for an example of how remedies are created.)

- Water has a memory: the more you dilute the substance, the more powerful its effect. And I mean dilute. The 30C “potency” is a common dilution used in homeopathy – that’s a dilution of 10-60. If something has been diluted this much, you would have to give two billion doses per second, to six billion people, for 4 billion years, to deliver a single molecule of the original, pre-diluted material. The result is that most homeopathic remedies are completely inert, and don’t contain a single molecule of what’s on the label. Whether bottled as a liquid or dripped onto lactose and sold as tablets, they are pure placebo.

Despite the implausibility of homeopathy, and its detachment from the increasingly science-based practice of medicine, it retained some popularity over time, with a resurgence in the past few decades as an “alternative” medical system. Rigorous clinical trials confirm what basic science predicts: homeopathy’s effects are placebo effects. While there are plenty of clinical trials that show homeopathy is associated with positive clinical effects, they are always small, poorly controlled, and often biased. Two comprehensive reviews of the evidence are the 2010 Evidence Check from the United Kingdom’s House of Commons Science and Technology Committee and the 2014 Australian National Health and Medical Research Council review, which reached the following conclusion:

Based on the assessment of the evidence of effectiveness of homeopathy, NHMRC concludes that there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective.

Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness. People who are considering whether to use homeopathy should first get advice from a registered health practitioner. Those who use homeopathy should tell their health practitioner and should keep taking any prescribed treatments. The National Health and Medical Research Council expects that the Australian public will be offered treatments and therapies based on the best available evidence.

What’s the problem with homeopathy in pharmacies?

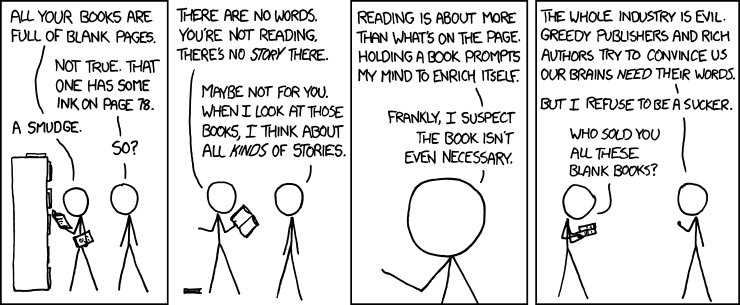

If homeopathy actually works in the way envisioned by Hahnemann and homeopaths, then the rest of medicine wouldn’t work. It is fundamentally incompatible with a scientific understanding of medicine, biochemistry, and even physics. However, when sold commercially, homeopathic “remedies” look like conventional medicine when they’re stocked on pharmacy shelves, like the photo above. The marketing and labeling of these “remedies” encourages this perception, often describing homeopathy as a “gentle” and “natural” system of healing, and putting cryptic terms like “30C” beside long Latin names of what are purported to be the active ingredients. So it is exceptionally difficult for the average consumer, who may never have heard of homeopathy, to understand that some of the products on the shelf may be inert. XKCD nailed the ethics of homeopathy in pharmacies several years ago (I pasted the hover text below):

“I just noticed CVS has started stocking homeopathic pills on the same shelves with–and labeled similarly to–their actual medicine. Telling someone who trusts you that you’re giving them medicine, when you know you’re not, because you want their money, isn’t just lying–it’s like an example you’d make up if you had to illustrate for a child why lying is wrong.”

Questions have been raised worldwide about the appropriateness of pharmacies selling homeopathy to consumers who may not realize what they’re buying. This was noted by the DC Court of Appeals in their judgement:

But, at this juncture, we cannot say that it is implausible that a reasonable consumer might understand appellees’ placement of homeopathic products alongside science-based medicines as a representation that the homeopathic products are efficacious or are equivalent alternatives to the FDA-approved over-the-counter drugs alongside which they are displayed.

What’s the basis of this lawsuit?

In 2020, the Superior Court dismissed CFI’s lawsuit because it failed to show it is a “nonprofit organization” or “public interest organization” within the meaning of the CPPA. The judge also stated that she did not find the marketing and product placement “to be an actionable representation, or to have the tendency to mislead under the CPPA”. She noted that “homeopathic” appeared on the front of the box as well as the federally-mandated disclaimer that the product had not been evaluated by the FDA (what has been called the “quack Miranda” disclaimer). The Walmart lawsuit was dismissed for similar reasons.

The Appeals Court disagreed. It accepted that CFI had a sufficient stake in the CPPA action and noted CFI’s activities regarding the regulation, testing, and marketing of homeopathy “align with consumers’ interests”. It also accepted that allegedly misleading product placement was within the scope of the CPPA. They describe a 2017 case brought forward under different state consumer-protection laws where obsolete motor oils were sold to consumers by placing them on shelves next to non-obsolete oils. The federal court denied a motion to dismiss that case based on the argument of “failure to recite a cognizable deceptive practice” even though there was a label on the oil stating it was unsuitable for most gasoline engines built after 1988. They also cited a case where CVS sold “Infant’s Acetaminophen” which was exactly the same as the CVS “Children’s Acetaminophen” but with a different photo on the package, and higher cost. The court was “…unable to conclude as a matter of law that no reasonable consumer would be deceived” even though both packages disclosed that they contained acetaminophen 160mg/5mL.

Finally, the appeals court disagreed with the superior court’s assessment that the placement of these products alongside “science-based medicines” did not have the tendency to mislead under the CPPA:

In this case, we do not find it facially implausible that a reasonable customer could believe, based on appellees’ placement of homeopathic drug products alongside FDA-approved over-the-counter drugs, that homeopathic products are comparably efficacious. We agree with CFI that whether signage and product placement influence consumers regarding the efficacy of medical products is a question that can be answered only with evidence, “not an inherently implausible assertion that can be dismissed out of hand.”

It also noted,

CFI’s complaints contains a number of conclusory allegations, but also contain numerous factual allegations and accompanying photographs to the effect that: the defendant retailers market themselves as offering products that will enable customers to get healthy; persons suffering an ailment will often turn to the pharmacy section of their neighborhood Walmart (or CVS) for relief; studies and patient experience have shown that homeopathic products are not effective; Walmart and CVS present homeopathic products alongside FDA-approved over-the-counter products, under aisle signs indicating that the aisles contain remedies for pain, colds, heartburn, and other conditions; and the retailers do so without informing customers that there is no scientific evidence that homeopathic products have any value in treating those symptoms and diseases. These factual allegations plausibly support an inference that, through their product placement practices, Walmart and CVS mislead consumers into believing that homeopathic products are equivalent alternatives to FDA-approved over-the-counter drugs.

What happens next?

This looks like a victory, but only re-opens the path for the original lawsuits, which can now proceed. The CFI Legal Director, Nick Little, concluded:

The Court of Appeals rightly recognized that giant retailers can’t just deny responsibility for how they present what are fundamentally worthless products. It’s a huge victory for consumers and their right not to be misled…DC’s highest court acknowledged what we’ve always known – CFI’s decades of work against pseudoscience like homeopathy is consumer protection work. We’re not going away, and it’s time for CVS, Walmart, and all other retailers to stop misrepresenting homeopathy as medicine.