Source: timoelloitt.com

Casey, our Labrador Retriever, started limping before she was a year old. Investigations confirmed dysplasia, a genetic condition that leads to degenerative joints, arthritis, and pain. We were devastated. After considering the few treatment options that existed, we decided to skip surgery and treat it conservatively. I had no desire to start anti-inflammatory drugs, being acutely aware of the side effects from chronic use. I was familiar with a popular supplement with weak but somewhat promising evidence: We started giving her glucosamine and chondroitin supplements regularly. And we watched and waited.

It took some time, but Casey did appear to improve. We were thrilled. Life went on, and other than the occasional rough play session, Casey’s limping was mild, and she thrived. We continued the supplements, confident that we were doing good. But eventually I started paying attention to the emerging evidence on glucosamine and chondroitin. Once touted as a panacea for arthritis and joint pain, there had finally been some high-quality trials conducted – and the results were disappointing. I started to wonder if the supplements were really doing anything for my dog’s pain. Eventually I decided on a trial – so I stopped the supplements about seven years after I started them. Neither my wife nor I could notice any difference at all in her mobility. Nor did the veterinarian. We’d been fooling ourselves, spending hundreds of dollars in the process.

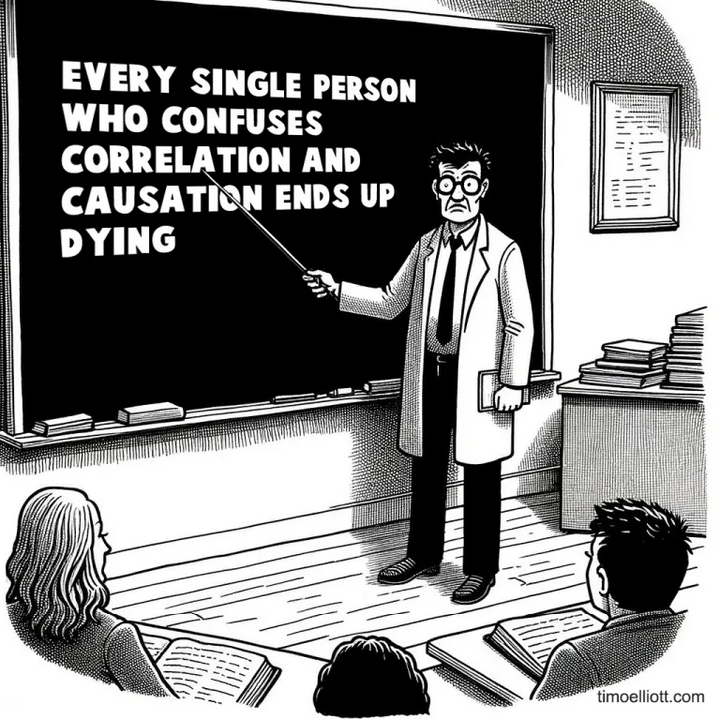

Post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this)

My experiment with glucosamine and chondroitin was definitely not the only time I’ve been subject to post hoc bias, but it’s the one that still stands out to me. Sometimes called the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, it attaches causality to a sequence of events.

Vaccine fears have been driven by the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. The early signs of autism may be observed to emerge at the same time children receive many vaccinations – in the first few years of life. This led some people to incorrectly infer a causal link between the two, simply based on the timing of events.

It’s not always harms where this fallacy may be observed. Just because your condition improves after a treatment, it doesn’t mean the treatment caused the improvement. Other possible factors could be at work, including mean reversion, time and natural healing, the placebo effect, or simply chance. Attributing an improvement to a treatment is often comforting for patients, easily explained to families, and convenient for clinicians. It’s also a quick and common explanation, that may be wrong.

Much of medicine is still filled with uncertainty. We don’t fully understand all disease mechanisms. We don’t always know why some drugs work in some patients and not others. If we’re not cautious about rigorously testing our assumptions, this logical fallacy can lead to wrong diagnoses, premature conclusions, overtreatment, and wasted resources.

Tunnel vision decision-making

Post hoc bias has not been not widely studied in medicine. In a paper published in September 2024 in JAMA Network Open, Donald Redelmeier and Eldar Shafir examined judgements in health treatments for signs of post hoc bias. Their hypothesis was that people would be more likely to continue treatments, even questionable ones, if they observed minor improvements in symptoms after initial care.

The researchers created different case scenarios about a patient with vague symptoms of unclear severity. Each case aimed to gather a treatment decision for a hypothetical patient by asking, “Would you recommend that [patient] continue or discontinue [treatment]?” Participants could choose from four options: “definitely continue,” “tend to continue,” “tend to discontinue,” or “definitely discontinue.”

Each scenario had two versions: an “improved version” where symptoms slightly improved after treatment, and an “unchanged version” where symptoms stayed the same. No scenario involved worsening symptoms that would suggest stopping the treatment. Otherwise, both versions were identical, involving the same patient and single question, and were randomly assigned.

Two different groups were surveyed: potential patients and healthcare professionals who regularly interact with patients. The largest group was public members recruited through the Prolific Survey platform. The second group included active community pharmacists who were approached in person at their workplaces during off-peak hours.

All participants completed the survey anonymously, were unaware of the study’s hypothesis, and only saw one scenario without knowing about alternative versions. Community participants took the survey online and were compensated. Pharmacists were approached with the script, “I would like to talk with a pharmacist,” and additional replies were prepared using “secret shopper” methods.

The Scenarios and the responses

Antibiotics

The first case involved using antibiotics against medical advice. The improved and unchanged versions were the same, except for one sentence in bold:

“JL is a 35-year-old schoolteacher. She has a sore throat and starts an antibiotic treatment from an unused prescription offered by a friend. According to medical science, however, misusing antibiotics might eventually cause resistant organisms. The next day JL feels better [unchanged]. Would you recommend she continue or discontinue the antibiotic?”

300 people participated—150 saw the improved version, and 150 saw the unchanged version. More people recommended continuing the antibiotic when JL felt better than when symptoms were unchanged (67 people [45%] vs. 25 people [17%]). This showed a moderate increase in support for continuing treatment (OR, 3.98; 95% CI, 2.33-6.78; P < .001).

Sugar supplement

This scenario involved a sugar supplement for insomnia: Only the bold text changed:

“GD is a 45-year-old administrator. She has irregular insomnia and starts a sugar powder supplement in the hopes of getting better sleep. The next week her sleep is better [unchanged]. Would you recommend she continue or discontinue the sugar powder supplement?”

200 people participated, divided equally between the two scenarios. More recommended continuing the sugar when symptoms improved (83%) (vs. unchanged (17%)). This showed a strong increase in support for continuing treatment (OR, 22.77; 95% CI, 10.99-47.18; P < .001).

Acupuncture

This scenario involved a family member suggesting acupuncture to a young woman with neck pain. Only the bold text differed:

KA is a 30-year-old flight attendant. She feels intermittent neck pain and starts acupuncture for relief (suggested by her grandmother). The next week she feels better [unchanged]. Would you recommend she continue or discontinue the acupuncture?”

198 individuals responded: 100 received the “improved” version and 98 the “unchanged” version. More recommended continuing the acupuncture if symptoms were reported to improve [87%] than when symptoms were unchanged [28%]. (OR, 15.27; 95% CI, 7.46-31.27; P < .001)

Copper Bracelet

This scenario involved a bracelet advertised and promoted for wrist pain. Only the bold text differed:

“MB is a 45-year-old accountant. She feels intermittent wrist pain and starts wearing a copper bracelet for pain relief (advertised in a magazine). The next week she feels better [unchanged]. Would you recommend she continue or discontinue the copper bracelet?”

199 individuals responded: 100 received the “improved” version and 99 the “unchanged” version. More recommended continuing using the copper bracelet after symptoms were reported to improve [78%], than when symptoms were unchanged [25%]. (OR, 16.19; 95% CI, 5.32-19.52; P < .001)

Shampoo Scenario

This scenario involved “horse shampoo” and baldness – about as ridiculous as you can get:

“DK is a 75-year-old retired professor. He is going bald and starts applying horse shampoo once per day. However, researchers typically agree horse shampoo does not promote hair growth. A couple of weeks later his hair seems better [unchanged]. Suppose he is undecided and asks you, would you recommend DK continue or discontinue the horse shampoo?”

400 individuals responded: 200 received the improved version and 200 the unchanged version. More recommended continuing the horse shampoo after symptoms improved [65%] than when symptoms were unchanged [7%] (OR, 23.30; 95% CI, 12.69-42.16; P < .001)

Vitamin Supplements: Public Responses

This scenario involved the use of vitamins for fatigue. In the absence of a deficiency, there is no evidence to support the use of vitamins to treat fatigue. Only the bold text differed:

“WS is a 30-year-old hospital nurse. He feels tired and starts a Vitamin B12 supplement for energy (despite normal B12 levels). The next week he feels better [unchanged]. Would you recommend he continue or discontinue the Vitamin B12 supplement?”

200 individuals responded: 100 received the improved version and 100 the unchanged version. Despite a normal baseline B12 level more recommended continuing after symptoms improved [80%] than when symptoms were unchanged [33%] (OR, 7.91; 95% CI, 4.18-14.97; P < .001)

Vitamin Supplements: Pharmacist Responses

This scenario involved pharmacists and a “secret shopper” in pharmacies:

“Hi, I am wondering if I can talk with a pharmacist? [Wait for pharmacist.] Last week I was feeling tired and started taking a Vitamin B12 supplement for energy. Now this week I feel better [unchanged]. Do you think I should continue or discontinue it?”

100 pharmacists were consulted, of whom 44 and 56 received the improved and unchanged versions, respectively. More pharmacists recommended continuing the treatment after symptoms improved [82%] than when the symptoms were unchanged [63%]. (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.04-6.52; P = .03)

This is disappointing, as pharmacists were more likely than the general public to recommend continuing vitamin B12 in the absence of any persuasive reason for use.

Conclusion: Beware Post Hoc Bias

This survey study revealed a consistent pattern of post hoc bias, where the public (and in one scenario, pharmacists) recommended continuing a treatment if they experienced or identified some subjective improvement, regardless of whether the treatment may or may not have caused it. As demonstrated by these often ridiculous examples, post hoc bias may lead patients and health professionals to persist with treatments that may be having no meaningful effects. The authors make an important observation that’s worth quoting in full:

Clinicians often acknowledge complexity in the aftermath of failure – namely, patient outcomes are uncertain. That same humility can feel less likely in the aftermath of a success where adherence to scientific discipline can be difficult following a treatment initiated by the responsible clinician. Personal motivations might further reinforce undue confidence after an improvement since clinicians want to believe their work makes a positive difference. Faulty attribution may be further exacerbated when the clinician interacts with a grateful patient, appreciative family, and impressed colleagues. In short, the system surrounding care helps perpetuate the post hoc bias.

Post hoc bias may feel intuitive, but it’s not necessarily accurate. While post hoc reasoning makes sense when the diagnosis is clear and treatment effects are well known, it may lead to complacency and not seeking effective treatments – one of my primary criticisms of alternative medicine. Recognizing this bias is a key first step to minimizing its influence.