EDITOR’S NOTE: Because I am at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in Chicago, between the meetings, working on a policy statement, working on a manuscript, and various other miscellaneous tasks, I alas was unable to produce a post worthy of the quality normally expected by SBM readers. Fortunately, Lorne Trottier, who’s done a great job for us twice before, was able to step in again with this great post about “safe” cell phone cases. Speaking of the manufactroversy over whether cell phone radiation causes brain cancer, there’s a session at the AACR that I’ll have to try to attend entitled Do Cell Phones Cause Brain Cancer? Who knows? It might be blogging material. I also might post something later that those of you who know of my not-so-super-secret other blog might have seen before. However, I often find it useful to see how a different audience reacts. Now, take it away, Lorne…

Pictured: The evolution of cancer? No.

In May of last year, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) issued a press release (1) in which it classified cell phones as Category 2B, which is “possibly carcinogenic to humans“. This ruling generated headlines world wide. Alarmist groups seized on it and now regularly cite this report to justify their concerns for everything ranging from cell phones to WiFi and smart meters.

IARC maintains a list of 269 substances in the 2B category, most of which are chemical compounds. A number of familiar items are also included in this list: coffee, pickled vegetables, carbon black (carbon paper), gasoline exhaust, talcum powder, and nickel (coins). The IARC provides the following definition of the 2B category (2 P 23): “This category is used for agents for which there is limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans and less than sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals. It may also be used when there is inadequate evidence of carcinogenicity in humans but there is sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals“.

The Category 2B “possible carcinogen” classification does not mean that an agent is carcinogenic. As Ken Foster of the University of Pennsylvania pointed out to me. “Their conclusion is easy to misinterpret.” “Saying that something is a “possible carcinogen” is a bit like saying that someone is a “possible shoplifter” because he was in the store when the watch was stolen. The real question is what is the evidence that cell phones actually cause cancer, and the answer is — none that would persuade a health agency.”

None the less this ruling was highly controversial. Expert groups of most of the world’s major public health organizations have taken the same position as the European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) which had stated that (3 P 8): “It is concluded from three independent lines of evidence (epidemiological, animal and in vitro studies) that exposure to RF fields is unlikely to lead to an increase in cancer in humans“. The representative of the US National Cancer Institute walked out of the IARC meeting before the voting. The NCI issued a statement (4) quoting other studies stating that: “overall, cell phone users have no increased risk of the most common forms of brain tumors — glioma and meningioma“.

Immediately following the IARC decision the WHO issued a reassuring new Fact Sheet (5) on mobile phones and public health: “A large number of studies have been performed over the last two decades to assess whether mobile phones pose a potential health risk. To date, no adverse health effects have been established as being caused by mobile phone use”. Since this controversial IARC classification, several new papers have been published that substantially undermine the weak evidence on which the IARC based its assessment.

The evidence that IARC cited to support its assessment was poor to begin with. Their initial press release (1) was followed by a more complete report that was published in the July 1, 2011 issue of the Lancet Oncology as well as online (6). In this article, I will review the evidence cited by IARC in support of its conclusion. I will also review updates from new papers published over the past year that cast further doubt on IARC’s conclusion.

Brain cancer incidence rates

Brain cancer is one of the rarer forms of cancer. In Canada, it ranks as #15, well below the leading cancers such as lung, breast, and prostate. There are more than 5 billion cell phones in the world. The fact that brain cancer incidences rates have remained flat in the US and elsewhere is one of the simplest and strongest indicators that cell phones do not cause cancer. Yet in the Lancet article, IARC dismisses the value of studies of brain cancer incidence rates with the statement that they “have substantial limitations because most of the analyses examined trends until the early 2000s only“. This is surprising, since at the time of IARC’s assessment there were already a couple of studies that found flat cancer incidence rates up to the end of 2006 in the US (7) and 2007 in the UK (8). These important papers are certainly past the “early 2000s”.

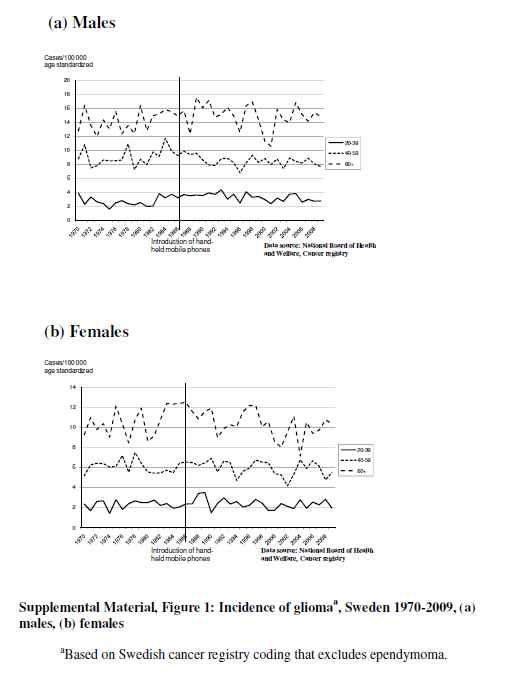

In the same month as the IARC assessment, a new study was published online in Environmental Health Perspectives that examined brain cancer incidence in Sweden up to the end of 2009 (9). Fig 1 of the Supplemental Material (see below) shows that brain cancer incidence rates in Sweden were essentially flat up to 2009. Furthermore, in the past year two more studies have been released which looked at cancer incidence rates up to 2008 in the Nordic countries (10) and the US (11) respectively. All of these papers show no increase in brain cancer. Thus the IARC statement dismissing the flat brain cancer incidence rate statistics because they: “examined trends until the early 2000s only” is simply not accurate. The fact that brain cancer rates are unchanged to date continues to be the simplest and strongest indicator that cell phones do not cause cancer.

Fig 1: Incidence Rates of Glioma in Sweden 1970 – 2009 (from 9)

Epidemiologic studies

In making its assessment, IARC relied primarily on two epidemiological studies including Interphone (12), and the Swedish group of Hardell et al (13). It is important to examine these studies in greater detail in order to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence on which IARC based its assessment. Some new studies also shed important new light on this evidence.

There are two basic kinds of such studies: case control and cohort studies. In the case control studies on cell phones, subjects diagnosed with brain cancer respond to a questionnaire about their past history of cell phone use. Their responses are compared with those of controls who do not have brain cancer. The results are tabulated to produce an OR or “odds ratio” of developing brain cancer as a function of past use. An OR of 1 means no risk. An OR of 2 means a 2X risk. Case control studies suffer from a number of limitations, of which the most serious is “recall bias”. The results are entirely dependent on the accuracy of memory of brain cancer patients and control subjects regarding their past cell phone use.

The occurrence of recall bias, in which brain cancer patients overestimate past cell phone use in comparison to controls, has been documented in a recent study (14). “In conclusion, there was little evidence for differential recall errors overall or in recent time periods. However, apparent overestimation by cases in more distant time periods could cause positive bias in estimates of disease risk associated with mobile phone use.”

Cohort studies are another type of epidemiologic study. Cohort studies follow a population of cell phone users over a period of time and monitor how many develop brain cancer. Cohort studies are generally more robust than case control studies because exposure is more reliably assessed, using records rather than individual memory. A series of “retrospective” cohort studies were done in Denmark (15, 16). The Danish studies are “retrospective” because they used existing cell phone records to establish the number of years subjects had been using their phones. Accessing government medical records, they determined which cell phone users developed brain cancer. From this they were able to assess if the risk of developing brain cancer increased with the number of years of cell phone use. These studies have the advantage of not depending on memory. They are limited however by the uncertainty of whether the subscriber was the actual user, and the necessary elimination of business phones (the names of individual business users were not available). The initial studies (15) involved 420,095 subjects, some of whom had used cell phones for up to 21 years. No cancer risk was found.

The Danish group released another study (16) in Oct 2011 after the IARC assessment (1 ,6). In this follow up study the number of person years of long term users was much higher than any previous study. “We followed up the mobile phone subscriber study to 2007, with a focus on tumours of the central nervous system. Longer follow-up increased the numbers of person years for subscribers, particularly in long term subscribers (≥10 years), in whom the total of person years under risk increased from 170,000 to 1.2 million”. Their conclusion for long term users was: “When restricted to individuals with the longest mobile phone use—that is, ≥13 years of subscription—the incidence rate ratio was 1.03 (95% confidence interval 0.83 to 1.27) in men and 0.91 (0.41 to 2.04) in women”

Because this series of studies was based on hard data, it is generally considered quite solid. Surprisingly, IARC dismissed these studies with the statement that: “In this study, reliance on subscription to a mobile phone provider, as a surrogate for mobile phone use, could have resulted in considerable misclassification in exposure assessment”. The NCI (4) took the opposite view of IARC by saying this about these studies: “Furthermore, a large population-based cohort study in Denmark has found no evidence of increased risk of brain tumors”.

The Hardell et al. studies

In making its assessment, IARC (1 & 6) relied primarily on case control studies including Interphone (12), and the Swedish group of Hardell et al (13). “A Swedish research group did a pooled analysis of two very similar studies of associations between mobile and cordless phone use and glioma, acoustic neuroma, and meningioma”. Most epidemiologists consider that Hardell is an outlier in the scientific literature (20).

The Hardell study (13) which IARC used in its risk assessment appears to be a rehash of a pair of similar papers published in 2006 (17 & 18). It is curious the Hardell timed the release of this “new” study just before the IARC meeting. In other words, Hardell repackaged a couple of old papers based on data collected in 2003, originally published in 2006, and then republished in 2011. At the time of the original publication, Hardell’s “pooled analysis” studies generated something of a media sensation. A number of expert groups felt compelled to comment on and critique these studies.

The FDA issued the following statement: “The FDA received numerous media inquires about a recently published paper (Pooled analysis of two case–control studies on use of cellular and cordless telephones and the risk for malignant brain tumors diagnosed in 1997–2003by Hardell et al.)…. The results reported by Hardell et al. are not in agreement with results obtained in other long term studies. Also, the use of mailed questionnaire for exposure assessment and lack of adjustments for possible confounding factors makes the Hardell et al. study design significantly different from other studies. These facts along with the lack of an established mechanism of action and absence of supporting animal data make it difficult to interpret Hardell et al. findings.

The same studies were also criticized by the EMF-NET which was established by the Institute for Health and Consumer Protect of the European Commission (19). Their report states that: “The results of the pooled study by Hardell et al. differ from most previously published studies, including the recently published studies with large numbers of long-term users”. The SCENIHR also criticized these studies (3, P 17): “However, both studies are non-informative because of inappropriate exclusion criteria and combination of studies”.

A 2009 paper by the Ahlbom et al on behalf of ICNIRP (International Commission for Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection) Standing Committee on Epidemiology (20) did a systematic review of the epidemiologic studies of cell phones and cancer. This paper had this to say about Hardell’s studies: “The studies by Hardell et al. are particularly problematic because of variation across their publications in the exact constitution of case groups, criteria for exclusion, exposure definitions, and the selection of results for presentation in the multiple overlapping publications….all studies found risk estimates close to or below unity, except the 2 most recent studies by Hardell et al., where up to 4-fold risk increases were reported. It is interesting to note that at the meeting where the IARC made its assessment, Alhbom was removed because he served as a board member of his brother’s telecommunications company. But Hardell remained and was permitted to vote despite the fact that he has testified as an “expert witness” in litigation by brain cancer patients against cell phone companies and has probably earned fees doing so. In any case, he got to vote on the merits of his own paper.

Despite all these criticisms, IARC used Hardell’s rehashed paper as primary evidence in its assessment. “Although both the INTERPHONE study and the Swedish pooled analysis are susceptible to bias—due to recall error and selection for participation—the Working Group concluded that the findings could not be dismissed as reflecting bias alone, and that a causal interpretation between mobile phone RF-EMF exposure and glioma is possible”. IARC could not dismiss Hardell’s results on the basis of recall bias even though studies such as (14) have shown that this is a likely source of error.

Over the years Hardell et al. have published more epidemiologic studies on cell phones than any other researcher. Virtually all his studies have used the same methodology of mailed questionnaires to establish the level of cell phone use. He has presented his findings in many different ways including by type of telephone (analog and digital cell phones as well as cordless phones), brain cancer type, cumulative hours of use, and number of years of use. Virtually every one of his studies has concluded that cell phones (and wireless and cordless phones) increase the risk for brain cancer.

Testing Hardell

If Hardell is correct in his finding that cell phone use causes brain cancer, this should cause an increase in brain cancer incidence rates. The fact that these rates have remained flat over the 25 years since cell phones were introduced and the roughly 15 years since use became widespread and common in the population can now be used to test some of his findings. In the paper cited by IARC (13), the Hardell finding that cancer risk increases with the number of years is easy to test. Table II (reproduced below) of Hardell’s paper (13) shows cancer risk increasing over the three latency periods listed. The highest risk is for >10-year latency with an OR of 2.1, 2.5 and 1.6 for wireless phones, mobile phones and cordless phones respectively.

Table II From (13): Pooled analysis of case-control studies on malignant brain tumours and the use of mobile phone; Hardell et al.; Intl Journal Oncology 2011 38: 1465-1474

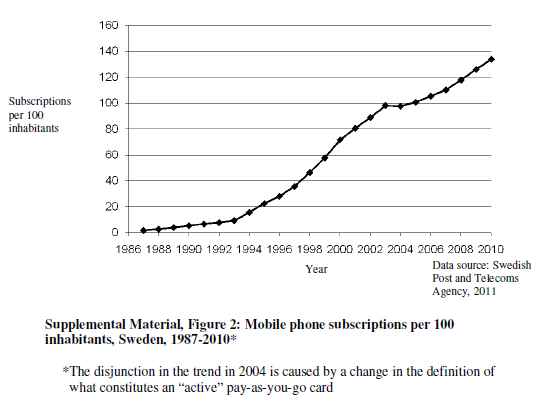

Fig 1 of Swerdlow’s (9) Supplementary Data that I referred to earlier shows that brain cancer incidence rates in Sweden were essentially flat up to 2009. Fig 2 below shows the history of cell phone subscriptions in Sweden from 1987 — 2010. This chart shows that in 1999 (10 years before 2009), approximately 50% of the population of Sweden had a cell phone. Using Hardell’s finding that >10 year mobile cell phone users have a 2.5 OR, simple arithmetic predicts that brain cancer incidence should increase by 75%:

(50% pop nonuser x OR 1) + (50% pop cell phone users x OR 2.5) = Average OR 1.75.

But there is no change. It is interesting to note that Hardell also conducted his studies in Sweden – the same country as Swerdlow’s data. Hardell’s finding on users >10 years is flatly contradicted.

Hardell’s case control studies as INTERPHONE were entirely dependent on the memory of people suffering from brain cancer. The IARC report states that Hardell used “Self-administered mailed questionnaires were followed by telephone interviews to obtain information on the exposures and covariates of interest.” As we have noted “recall bias” (14) is a major potential source of error in this these studies. The hard data from the Swedish cancer incidence rates and cell phone subscriptions is reliable and it flatly contradicts Hardell.

Fig 2: Cell phone subscriptions in Sweden 1987 – 2010 (from 9)

Since the publication of the paper by Swerdlow et al. (9) other major studies have been published that used brain cancer incidence data to explicitly test the findings of Hardell’s case control studies. A study (10) by Deltour et al. did an extensive analysis of brain cancer incidence rates against cell phone subscription history using data from the Nordic countries. It tested various values of OR and latency, including those Hardell claims to have found. The conclusion states: “Several of the risk increases seen in case-control studies appear to be incompatible with the observed lack of incidence rate increase in middle-aged men. This suggests longer induction periods than currently investigated, lower risks than reported from some case-control studies, or the absence of any association”.

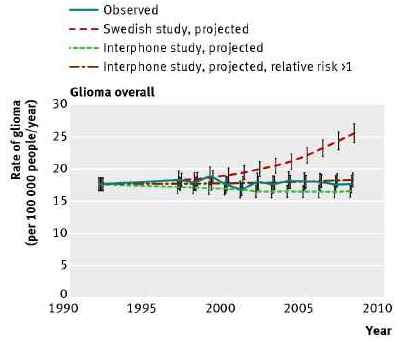

Another rigorous study which tested Hardell’s results was authored by scientists from the National Cancer Institute Little et al. (11). “In this study, we compared the observed patterns for glioma incidence trends in the US in 1992-2008 with projected incidence rates for the same period based on relative risks reported by the two epidemiological studies forming the basis of the IARC Working Group classification”. Their conclusion states: “Raised risks of glioma with mobile phone use, as reported by one (Swedish) study forming the basis of the IARC’s re-evaluation of mobile phone exposure, are not consistent with observed incidence trends in US population data, although the US data could be consistent with the modest excess risks in the Interphone study”. Their results are best illustrated with one of the graphs from the study (Fig 3). From this it is clear that Hardell’s findings (dashed red line) diverge sharply from the actual cancer incidence trend. It is also clear why they could draw no conclusion concerning the Interphone results, since modest risks implied by some of the Interphone results produced a flat cancer incidence curve.

Fig 3: NCI Brain cancer incidence rate projections vs. observed (From 11)

The Interphone study

It is important to remember that even though the Interphone study (12) found a modest increase in cancer risk in a subset of the study, the overall conclusion was: “Overall, no increase in risk of glioma or meningioma was observed with use of mobile phones. There were suggestions of an increased risk of glioma at the highest exposure levels, but biases and error prevent a causal interpretation. The possible effects of long-term heavy use of mobile phones require further investigation”. It is interesting to note that while the authors of Interphone understood that “biases and error prevent a causal interpretation”, IARC none the less cited Interphone to support its “possibly carcinogenic” ruling.

The only part of Interphone with a significant “positive” result was an OR of 1.4 for glioma in the 10th decile of call time (> 1640 cumulative hours of use). However this result was contradicted by the results for cumulative number of calls where the OR was less than 1 even for the highest decile. A close look at the “positive” call time data shows another glaring inconsistency. Among users with the highest call time the OR is 3.77 for people with 1 – 4 years of use, OR of 1.28 for 5 – 9 years, and OR of 1.34 for > 10 years of use. There is no logical progression with time — no dose response relationship. These inconsistent results are most likely due to recall bias and other errors. As a result, the authors of Interphone refrained from drawing any conclusion. For a more complete analysis of the Interphone study see (* 21).

Other items in IARC’s report

The IARC report in the Lancet (6) included a reference to a study (22) by Cardis et al. which attempts to correlate the physical location of gliomas in the brain with the area of maximum radiation from the cell phone. IARC makes the following statement in connection with this study: “Associations between glioma and cumulative specific energy absorbed at the tumour location were examined in a subset of 553 cases that had estimated RF doses. The OR for glioma increased with increasing RF dose for exposures 7 years or more before diagnosis, whereas there was no association with estimated dose for exposures less than 7 years before diagnosis”. In other words, this study claims to have found a higher risk of glioma in parts of the brain receiving the highest energy.

It is interesting to note that the original IARC press release (1), contained a reference to another paper by Larjavaara et al (23) that examined the same issue. The Larjavaara paper (23) is listed in note 4d of the press release. However, this study reached the opposite conclusion of the Cardis paper (22). The Larjavaara abstract included the following conclusion: “These results do not suggest that gliomas in mobile phone users are preferentially located in the parts of the brain with the highest radio-frequency fields from mobile phones“. At the time, I found it curious that the IARC would reference a study that seems to contradict their precautionary 2B categorization of cell phone EMF. But what is most surprising is that in its report one month later in the Lancet (6), IARC had dropped any reference to this paper!! Again it is worth noting that Elizabeth Cardis also served on the IARC committee and voted to have her own paper count as evidence for the “possible carcinogen” ruling.

Conclusion: Cell phones probably aren’t category 2B carcinogens

From all this it would appear that the decision making process in which IARC classed cell phones under Category 2B as “possibly carcinogenic” was flawed. IARC was ill informed on the true state of studies of brain cancer incidence rates, claiming that (6) “most of the analyses examined trends until the early 2000s only“. It ignored numerous warnings by expert groups who had determined that the case control studies by Hardell et al. were outliers in the literature. It accepted a reincarnation of an old study (13, 17, 18) that had been roundly criticized. It undervalued studies which established the existence of recall bias (14) with the statement that: “the Working Group concluded that the findings could not be dismissed as reflecting bias alone, and that a causal interpretation between mobile phone RF-EMF exposure and glioma is possible”. IARC undervalued the solid cohort studies (15, 16) by Schutz et al. of Denmark. “In this study, reliance on subscription to a mobile phone provider, as a surrogate for mobile phone use, could have resulted in considerable misclassification in exposure assessment”

Since the IARC published its report the evidence against its conclusion has grown stronger. Three new studies (9, 10, 11) of cancer incidence rates have shown that rates have remained flat up to at least 2009. The findings of Hardell et al. have been put to the test in these same three studies. A large portion of Hardell’s results (13) have been shown to be wrong. This undermines one of the main pillars for IARC’s finding. The authors of Interphone (12), the other main pillar have stated that biases and error prevent a causal interpretation of their results. Finally, IARC appears to have been disingenuous in removing reference to a study (23) that contradicted one of the papers cited in their final report in the Lancet.

As the WHO stated in their updated Fact Sheet of June 2011 (5): “A large number of studies have been performed over the last two decades to assess whether mobile phones pose a potential health risk. To date, no adverse health effects have been established as being caused by mobile phone use”. While it is still cannot be ruled out that brain cancer incidence rates might increase in the future — say if latency is 20 years or more – this appears to be increasingly improbable. It is unfortunate that the IARC decision making process was flawed. But it is unlikely that IARC will ever change its Category 2B classification. Like coffee and pickled vegetables, cell phones may well remain in this category forever. IARC lists a grand total of one substance under category 4 which is “The agent is probably not carcinogenic to humans”. Alarmist groups will continue to exploit and misrepresent this flawed ruling.

See our website for more science based information on the issue of EMF and health (www.emfandhealth.com).

References

- Open article: IARC Press Release May 31, 2011: http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2011/pdfs/pr208_E.pdf Return to text

- Open Article: IARC Document on Carcinogens: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Preamble/CurrentPreamble.pdf Return to text

- Open document: European Commission Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCEHINR): Report Health Effects of Exposure to EMF Jan 2009: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/04_scenihr/docs/scenihr_o_022.pdf Return to text

- Open article: NCI Statement: International Agency for Research on Cancer Classification of Cell Phones as “Possible Carcinogen” May 31, 2011: http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/2011/IARCcellphoneMay2011 Return to text

- Open article: WHO Fact Sheet: Electromagnetic fields and public health: mobile phones June 2011: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs193/en/index.html# Return to text

- Open article: IARC follow up report July 1, 2011 Lancet Oncology and online: http://press.thelancet.com/tloiarcsum.pdf Return to text

- Open Access: Brain cancer incidence trends in relation to cellular telephone use in the United States; Inskip et al.; Neur-Oncology July 2010: http://neuro-oncology.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/07/16/neuonc.noq077.full.pdf+html Return to text

- Time Trends (1998-2007) in Brain Cancer Incidence Rates in Relation to Mobile Phone Use in England; Vocht et al.; Bioelectromagnetics July 2011, first published online Jan 28, 2011: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bem.20648/abstract Return to text

- Open access: Mobile Phones, Brain Tumors and the Interphone Study: Where Are We Now?; Swerdlow et al.; Environ Health Perspect; published online July 2011: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3226506/?tool=pubmed Return to text

- Mobile Phone Use and Incidence of Glioma in the Nordic Countries 1979–2008; Deltour et al.; Epidemiology Vol 23 No 2 Mar 2012: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22249239 Return to text

- Open Access: Mobile phone use and glioma risk: comparison of epidemiological study results with incidence trends in the United States; Little et al.; BMJ 2012; 344: http://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e1147 Return to text

- Interphone study; Cardis et al.; International Journal of Epidemiology May 2010; 39; 675–694 http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/39/3/675.full.pdf Return to text

- Pooled analysis of case-control studies on malignant brain tumours and the use of mobile phone; Hardell et al.; Intl Journal Oncology 2011 38: 1465-1474 Return to text

- Recall bias in the assessment of exposure to mobile phones; Vrijheid M J et al.; Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2009; 19: 369-81: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18493271 Return to text

- Open access: Danish cohort studies: Cellular Telephone Use and Cancer Risk: Update of a Nationwide Danish Cohort; Schuz et al.; JCNI J Natl Cancer Inst 2006 Vol 98 Issue 23: http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/98/23/1707.full Return to text

- Open access: Use of mobile phones and risk of brain tumours: update of Danish cohort study; Schuz et al.; BMJ Oct 2011; 343: http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d6387 Return to text

- Pooled analysis of two case–control studies on use of cellular and cordless telephones and the risk for malignant brain tumours diagnosed in 1997–2003; Hardell et al.; Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2006 79: 630–639 Return to text

- Pooled analysis of two case-control studies on the use of cellular and cordless telephones and the risk of benign brain tumours diagnosed during 1997-2003; Hardell et al.; Intl Journal Oncology 2006 28: 509-518 Return to text

- EMF-NET: Comments on the study by Hardell et al.: Pooled analysis of two case-control studies: http://web.jrc.ec.europa.eu/emf-net/doc/efrtdocuments/EMF-NET%20EFRT%20Hardell%20Paper%2024APR2006.pdf Return to text

- Epidemiologic Evidence on Mobile Phones and Tumor Risk: A Review Ahlbom et al. (Epidemiology 2009; 20: 639–652; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19593153 Return to text

- Commentary on the Interphone Study: http://www.emfandhealth.com/InterphoneStudy.html Return to text

- Risk of brain tumours in relation to estimated RF dose from mobile phones – results from five Interphone countries; Cardis et al.; Occup Environ Med 2011; 68: 631-640; http://oem.bmj.com/content/early/2011/06/09/oemed-2011-100155.abstract Return to text

- Location of gliomas in relation to mobile telephone use: a case-case and case-specular analysis; Larjavaara et al.; Am J Epidemiol 2011 Jul 1; 174(1): 2-11; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21610117 Return to text