Alternative medicine is big business. While it may have the image of small companies, personalized treatments, and independent practitioners, it is a multi-billion dollar industry that is growing rapidly. In contrast with our definition of science-based medicine, alternative medicine is arguably harder to define, as it encompasses a variety of treatments, practices and therapies that range from unproven to disproven, and includes not only drugs (herbal or otherwise), physical interventions, and even spiritual/metaphysical practices. What all of these practices have in common is that that they are not accepted as part of conventional medical practice, which is grounded in a standard of scientific evidence. While the practices are disparate, alternative medicine is generally seen as safer, even “gentler”, than conventional medicine.

Despite perceptions, serious harms from alternative medicine have been documented in the medical literature and in this blog. Beyond the obvious direct harms of a toxic therapy (e.g., treating children with autism with bleach), harms can also be caused by avoiding effective therapies in favour of ineffective ones. They reporting of harms from alternative medicine is believed to be less common than conventional medicine mainly because of the robust and mandatory (in places) reporting built into delivery systems for conventional medical care. In contrast most alternative medicine is provided privately, and regulatory oversight of most alternative medicine products and practices tends to be lighter (e.g., the licensing frameworks for supplements vs. over-the-counter drugs). Perceptions may also feed this reality, as consumers that believe these treatments are harmless may not attribute adverse events to alternative medicines/practices.

Because harms are poorly understood, a group of researchers led by Dr. Bernie Garrett recently undertook a process to define the types of risks associated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and to classify them into categories. The paper, entitled “A taxonomy of risk-associated alternative health practices: A Delphi study” was published in May 2021 and is open access.

The researchers used the Delphi method with a group of experts to develop a consensus document. Briefly, the Delphi method involves sequential group surveys with aggregated responses provided back to the group with the objective of finding consensus. They established a multi-disciplinary group of participants, including four physicians, four nurses, three pharmacists, three physiotherapists, two social workers, two lawyers (with expertise in harm and injury), an epidemiologist, a naturopath, and a chiropractor. During the course of the work, four individuals withdrew for different reasons (1xMD, 1xRN, 1xPT, 1xSW) leaving 17 in the panel.

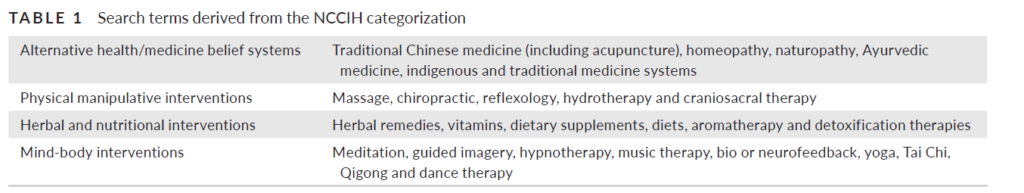

The panel started with a literature review that sought to identify articles, legal cases and media reports that involved harms of CAM. Search terms were informed by the NCCIH categorization, which David Gorski blogged about some time ago:

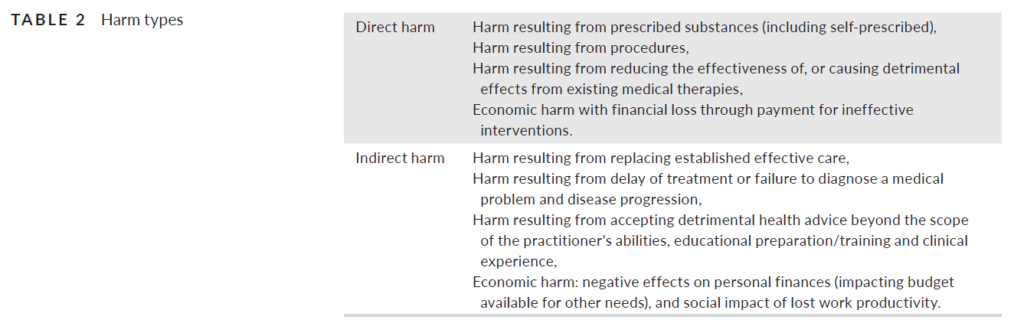

Search terms were combined with searches for reports of “harms, risks deaths, damage, injury” and “adverse events” resulting in over 1,700 articles. This formed the basis of a list that was developed and sent to the panel for comment. Panelists were asked for feedback on their agreement with the developed list, the categorization used, and the level of risk associated with each item. Five sequential rounds of consultation and analysis occurred. The types of harms were simplified into the following framework:

As one would expect with a group that includes a naturopath, a chiropractor, and an array of health professionals, arriving at consensus on harms and risks of CAM was described as “challenging” as the group was noted to have “diverse opinions”.

Given the absence of systematically-collected data on harms, it was not possible to quantify risks in terms of probability. Three categories (high/moderate/lower) of risk were created based on significance of the harm itself, the existence of verified case examples, and the potential consequences vs. value of treatment:

- Higher: exposes person seeking therapy (or others) to risk of serious and/or permanent physical or psychological harm, or death. Occurrences may be rare but the consequences are considered to outweigh any asserted potential value.

- Moderate: exposes person seeking therapy (or others) to risk of (potentially reversible) significant physical, psychological, or economic harm. Occurrences may be rare but the potential consequences may outweigh any asserted potential value.

- Lower: exposes person seeking therapy (or others) to a short-term risk of physical, psychological, or economic harm. Occurrences may be rare but indicate in some instances using it may be harmful.

A new definition of CAM

The authors note that NCCIH defines CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not considered to be part of conventional or allopathic medicine” and “a non-mainstream practice…used together with conventional medicine”. They note that the NCCIH definition depends on the cultural frame of reference – especially the term “complementary” which implies a therapy that is adjunctive to conventional care. The panel developed their own functional definition:

The range of therapeutics that largely originate from traditions and theories distinct from contemporary biomedical science, and which claim mechanisms of action outside of those currently accepted by scientific and biomedical consensus.

General harms

Many harms are not specific to any particular form of CAM. The following general harms were identified, with the level of harm in brackets.

- Using alternative health care instead of the existing biomedical standard of care for medically treatable conditions (higher)

- Using alternative therapeutics which are new and where side-effects are unknown (higher)

- Using alternative therapeutics alongside existing medical treatments without informing the medical provider (higher)

- Using alternative health treatments for diagnoses not currently recognized as biomedical illnesses or misdiagnosed (do not meet biomedical diagnostic criteria), for example, candida overgrowth, adrenal fatigue, chronic Lyme disease, etc. (moderate)

- Utilizing alternative health care for the treatment of medical conditions based on misinformation in deceptive advertising/marketing (moderate)

- Taking part in an alternative health research that has not been approved by an independent research ethics board (lower)

- Impact of the financial costs associated with the use of alternative practitioners/therapeutics not covered under public health care provision (lower)

- Societal economic impact associated with the use of alternative health care provision when covered by third parties (lower)

Alternative belief system harms

Some harms are unique to specific alternative medicine practices. The panel identified the following harms:

- Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

- Toxicity associated with specific TCM products – some products associated with cardiovascular, liver, kidney, and other harms. Some contain high levels of lead or mercury (higher)

- Injuries from cupping – bruising and burns which can be severe (moderate)

- Injuries from acupuncture – infection, trauma, collapsed lungs, and nerve damage (higher/moderate)

- Injuries from acupuncture with moxibustion – as above, plus burns (moderate)

- Injuries from acupuncture in vulnerable populations – increase risk of trauma/harm (lower)

- Naturopathic and homeopathic practices

- Adverse events with naturopathic intravenous therapies – including infections, contamination, use of illegal or compounded products (higher)

- Injuries from colonic irrigation therapies with water, coffee and other substances – including infections, tears and intestinal perforation (higher)

- Provision of anti-vaccination advice – common with naturopathic and homeopathic belief systems (higher)

- Ayurvedic practices

- Toxicity associated with specific remedies – numerous reports of lead poisoning, many medicines contain at least one metal (higher)

- Religious health advice and faith healing

- Negative consequences of accepting advice that conflicts with medical advice (higher)

Physical manipulative alternative health care activities

The third major class of harms involved manual therapies: chiropractic, osteopathy, and massage:

- Chiropractic

- Injuries from spinal manipulative therapy – including vascular dissection, stroke, and subdural hematoma; neurological damage; fractures. This includes an array of SMT activities. (varies from higher to lower)

- Injuries from spinal manipulative therapy in vulnerable populations or taking specific medications – including chiropractic in infants and children, the elderly, those with clotting disorders, etc. (higher to lower)

- Adoption of anti-vaccination advice – common in chiropractic, sometimes chiropractic is recommended instead of vaccination (higher)

- Massage therapy

- Injuries with massage therapy in the elderly – musculoskeletal injuries (lower)

- Osteopathic

- Injuries with prolotherapy injections – nerve damage when injections are performed near peripheral nerves (moderate)

Herbal and nutritional supplement therapies

- The problems with herbal remedies and dietary supplements have been well documented at this blog, and are similar to concerns about TCM products:

- Toxicity with specific remedies/supplements that contain metals – owing to a lack of quality control (higher)

- Toxicity with specific remedies/supplements that are adulterated with drugs – owing again to a lack of quality control (higher)

- Adverse effects of specific remedies/supplements – these may be unlisted on the product (higher)

- Adverse effects of remedies/supplements for weight loss – reports of kidney and liver damage (higher)

- Adverse effects of remedies/supplements used in vulnerable populations – such as use in pregnancy or while breastfeeding, or in the elderly (higher to moderate)

A new approach to understand the harms of CAM

Whether or not you are a user of CAM, everyone should be in favor of a safer system, where harms are minimized, documented, and accepted/understood by consumers. This is particularly important when the effectiveness is questionable or unclear, which is the case for the vast majority of CAM. These products and treatments are not innocuous and some are associated with reports of significant harm – even death. In this new paper, a diverse group of professionals reached a consensus on the types and severity of harms that can arise from complementary and alternative medicine. Further work could potentially build on this framework, in time providing providers and consumers alike with a better understanding of the risk and consequences of these therapies and treatments.