In the United States, the sudden and unexpected death of an infant, particularly during sleep, is the leading cause of mortality between the neonatal period (1st month of life) and a child’s first birthday. Despite this fact, and some significant advances that have been made over the past 30 years, the biological and pyschosocial factors involved in these deaths are still not fully worked out. A study in the May issue of Pediatrics doesn’t provide solutions to this problem, but it support what we do know about risk factors and it might help to shine a light on some of the gaps in our approach to prevention.

The study, which I’ll break down shortly, also reveals just how far we have to go in effectively educating infant caregivers on modifiable risk factors for unexpected infant death. We have come a long way when it comes to making sleep safer for babies, but this is a complex problem without easy answers. Even determining how to classify infant deaths has been challenging.

What is Sudden Unexpected Infant Death and when is it SIDS?

How we define outcomes in medicine plays an important role in how we study these outcomes and the variables that may or may not play a role in causing them. Historically, we haven’t done a great job when it comes to the unexpected death of infants and this has made large scale surveillance difficult. How can we learn which populations of infants are most at risk of unexpected death, or develop strategies for reducing their risk through research and targeted caregiver education if we don’t have a solid grasp of when these deaths occur and in what environments?

There have been several attempts to track these unexpected infant deaths over the years. These efforts have been hampered by varying definitions and the difficulty inherent in classifying events that tend to be unobserved by caregivers. In 2009, the CDC created a specific registry for sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) cases with the goal of supplementing death certificate data in order to add depth to our ability to map out the factors that might play a causal role. The key to this registry is the use of standardized definitions and criteria, as well as a focus on documenting detailed information from death scene investigations and autopsies, in order to break SUID into appropriate subgroups consistently. This could theoretically help us to tweak and focus existing risk reduction strategies, tailor our approach to education, and even tease out potential new avenues of research.

As defined by the CDC, SUID is a general category that includes all cases of both unexplained and explained unexpected deaths in infancy. The subgroup of explained cases contains those deaths attributed to accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed. This often involves a parent rolling on to a child, or a child becoming wedged between a caregiver and a couch cushion, but bedding or objects in the sleep space can also play a role. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) falls into the subgroup of unexplained cases but requires a thorough case analysis that includes an autopsy, death scene investigation, and evaluation of the clinical history. Without this degree of investigation, unexplained SUID cases are labelled as unknown cause.

The Back to Sleep Campaign and recent epidemiological trends

SIDS has long been recognized as the most common cause of death in infants after the first month of life. Prior to the early 1990s, when pediatricians in the United States and several other countries first began recommending supine sleep, the risk of SIDS was 1.2 out of every 1,000 live births. It was, and still is, much higher in Black and American Indian/Alaskan native children and slightly more common in boys for unclear reasons.

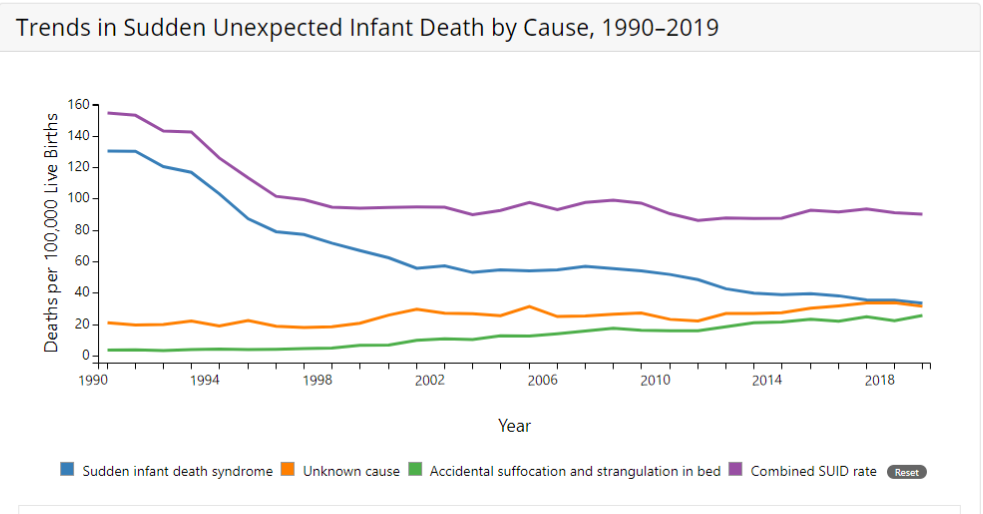

Cases of SIDS plummeted by more than 50% when parents began putting their babies to sleep on their backs. The campaign was a stunning success and has saved thousands of lives. Unfortunately, the steady decline in overall cases of SUID began to level off after a few years.

SIDS cases dropped dramatically deep into the 90s and have continued to fall ever since, though at a much less impressive rate:

See also the CDC SIDS dashboard.

Overall SUID rates naturally fell as well, for a while, likely because of refinement in our risk reduction strategies for safe sleep. Since the late 90s, however, they stalled because the decrease in SIDS cases has been matched by an increase in SUID cases attributed to suffocation or labelled as unknown.

Why are cases of SIDS continuing to fall, though less dramatically than they did immediately after the Back to Sleep campaign began, while other SUID subgroups are increasing in incidence? Some of it is obviously a diagnostic substitution. More complete investigations into SUID cases are certain to increase the likelihood of discovering a potential cause. More focus on consistent proper labeling might also result in less instances where a death was simply labelled as SIDS without a proper investigation out of ignorance or incompetence, thus bumping the number of cases in the unknown cause category.

Another potential explanation, sadly, is that caregivers might not be following safe sleep recommendations throughout infancy. SIDS tends to occur earlier in infancy, so perhaps some caregivers are becoming less focused on the modifiable risk factors after the highest risk in the first 2-3 months of life. This is where the psychosocial complexity of SUID comes in to play as there are seemingly infinite potential reasons for poor adherence to our recommendations: cultural practices, caregiver fatigue, a false sense of security, social or financial upheavals, inadequate counseling, etc.

I’m confident that there are potential explanations that I’m not smart enough to think of. And again, our ability to understand and manage this complicated problem is limited when our data is incomplete. This is where studies such as the one in Pediatrics that I mentioned above come into play.

CDC SUID data from 2011-2017

The study looked at the more than 12,000 SUID cases captured by the CDC registry from 2011 to 2017 with a more detailed and systematic approach than previous studies. For example, they used classification categories that did not overlap in order to avoid confusion and allow easier analysis. They found that 18% of deaths were fully explained by suffocation with another 13% possibly caused by suffocation. In 41% of cases, though suffocation couldn’t be determined, there were factors that clearly went against safe sleep recommendations. In total, 72% of SUID cases were associated with unsafe sleep and 74% of the cases where suffocation was proven or possible involved soft bedding.

One of the more interesting findings was that certain SUID cases trended a bit older than what would be expected based on earlier data. For example, cases that were unexplained but likely caused by suffocation had a mean age of 4 months. Historically SUID cases peak between 2-4 months, the bulk of which being SIDS. The study authors hope that having more detailed data such as this might help tease out different underlying causes and guide future research.

After analyzing the data, the authors determined key implications for pediatric healthcare professionals. Because more than 70% of SUID cases involved unsafe sleep environments, it is crucial that we figure out why caregivers aren’t following our recommendations. It is imperative that we develop more effective ways to educate these caregivers and help them adhere to the guidelines. One potential way to improve adherence and save infant lives would be to determine high risk groups and target educational outreach. The authors also call for improved documentation in the medical record, particularly involving autopsy and death scene investigations.