[Editor’s note: Two weeks’ ago Jonathan Howard highlighted some flaws in Dr. Jessica Hockett’s claims about the 2020 COVID-19 wave in NYC, extensively quoting a Twitter-based analysis Columbia’s Dr. Eric Burnett. Dr. Burnett has collaborated with Dr. Jonathan Laxton to provide a long-form post elaborating on the Twitter thread, which is presented below.]

COVID-19 denialism and disinformation have exacerbated the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and slowed the pandemic response in the U.S. Recently Hockett, who holds a Ph.D. in educational psychology, published a series of articles for the Brownstone Institute (e.g. this one). Using city-level data, she claims that the COVID-19 surge in New York City in the spring of 2020 was exaggerated. The Brownstone Institute relies on COVID-19 minimization techniques to help them forward their anti-lockdown, anti-mask, and anti-vaccine agenda and make such measures appear as overreactions and government overreach. Does Jessica Hockett present an accurate picture of COVID-19 in New York City? No, not even close.

Before getting too deep into this, you should know more about me. I am a board-certified internist and work as an academic hospitalist at a major NYC hospital (just an FYI, my views here are my own and don’t reflect those of my employer). This means I specialize in the care and management of hospitalized patients. I was one of the first physicians deployed to a COVID care team at my institution. I sat in on daily departmental meetings, which discussed how best to deploy COVID surge teams and map ICU and hospital bed capacity. I helped create a COVID patient care curriculum for our internal medicine residents so that we could all be kept up to date on the evidenced-based management of our patients. I was the attending physician for one of our COVID step-down units. I admitted and cared for hundreds of COVID patients throughout this pandemic. I bore witness to a tremendous amount of loss and human suffering, but I also saw the beauty in life’s fragility. This was my life for three months working in the epicenter of a global pandemic. My experience matters, and my expertise matters.

Hockett and her supporters have accused me of using appeals to emotion and authority to justify my claims. They feel as though I’m gatekeeping the analysis of these data, that I am saying only a doctor can express an opinion on this matter. Some have gone so far as to claim my “trauma-addled brain” is preventing me from remembering facts correctly. Let’s be clear, I don’t owe her or anyone else a response to such ludicrous claims. I could end this here and let my experiences and expertise serve as a rebuttal to her analysis, but I won’t. Hockett’s attempt at historical revisionism is not only disrespectful to the thousands of COVID victims and NYC frontline healthcare workers who sacrificed so much during the pandemic, but it also undermines public health efforts. It will make dealing with the next public health crisis much more difficult.

Please consider one thing while reading this post: which is the more likely scenario? Did thousands of healthcare workers in NYC, the media, and the lay public somehow band together to concoct an elaborate lie about hospitals being overwhelmed in the spring of 2020? Or did one person misinterpret data that she did not understand, arrive at the wrong conclusion and publish it on her Substack? Her claims have been debunked previously, such as this post by John Howard about the reality in New York. But I feel like an NYC hospitalist’s perspective is also called for. So, allow me to debunk Hockett’s claims, not with emotional appeals to authority, but with cold, hard facts.

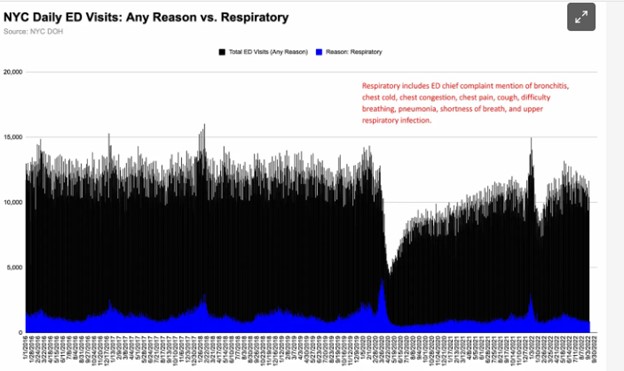

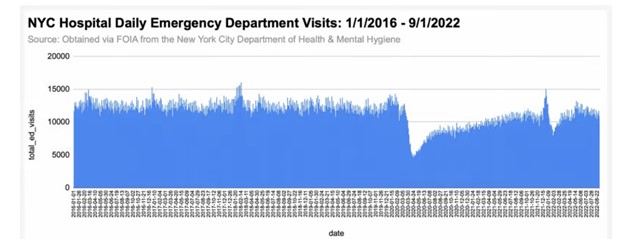

Claim one: NYC emergency departments were not overwhelmed due to decreased patient visits

In her posts, Hockett makes many assumptions about NYC in the spring of 2020. She has previously suggested that NYC hospitals were not overrun because emergency department (ED) volume decreased during that time.

This is a vast oversimplification and demonstrates a lack of understanding of hospital operations and how the pandemic affected ED visits. Healthcare systems can become overwhelmed for various reasons: staffing shortages, increased patient volume, increased patient acuity, an influx of more complex medical cases leading to an increased length of stay, and reduced bed capacity. The raw number of patients is not the only factor. The changes in ED patient volume were dynamic during the pandemic. This has been well documented in both the scientific literature and lay press.

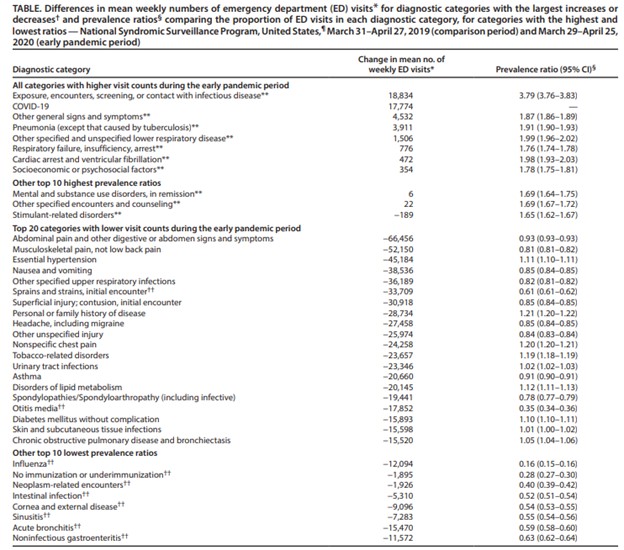

The CDC MMWR published data on the declining ED visits during the early stages of the pandemic, which showed some specific trends:

During the early 4-week interval in the COVID-19 pandemic, ED visits were substantially lower than during the same 4-week period during the previous year; these decreases were especially pronounced for children and females in the Northeast. In addition to diagnoses associated with lower respiratory disease, pneumonia, and difficulty breathing, the number and ratio of visits (early pandemic period versus comparison period) for cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation increased.

As you can see in this table, minor conditions such as muscle and joint pain/injuries, sprains, urinary tract infections, high blood pressure, headaches, and other less urgent presentations decreased significantly. Other studies have confirmed decreases in presentations with non-fatal trauma (25% decrease), motor vehicle-related injuries (23.3% decrease), and injuries related to falls (25.1% decrease). If people are staying home due to pandemic health orders, you can see why these presentations would decline. Many of these conditions were handled by telehealth visits to decompress the emergency department and create space/resources for the ever-growing number of COVID-19 patients. An increase in critically ill COVID-19 patients can quickly consume the resources normally used to manage less-urgent patients. You can imagine that 30 patients in multi-organ failure, requiring central line placement, intubation, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, emergent diagnostic imaging, and CPR are much more burdensome and overwhelming to the healthcare system than 100 people with non-urgent concerns. The resources freed up by reductions in non-urgent visits were not enough to offset the requirements of COVID-19 patients.

Claim two: NYC emergency departments were not overrun by people with COVID-19

Hockett claims:

Only 3% of the people who came to New York City hospital EDs during the spring 2020 March-May wave were clinically diagnosed* with the virus. At no point did the percentage of visits to NYC hospital EDs with a COVID diagnosis exceed 10%.

*Per NYC department of health, a clinically diagnosed COVID ED visit is ‘a visit with an ICD-10 discharge diagnosis cde of U07.1 or a SNOMED code of 840539006.’ A clinical diagnosis does not have to include a laboratory-confirmed test for SARS-CoV-2, but a positive test irrespective of symptoms would receive diagnosis.

This argument assumes the EDs were not overrun with COVID-19 patients because there were few COVID-19 diagnoses based solely on ICD-10 codes. There are a few issues with this observation.

- Testing in the beginning weeks of the pandemic was very limited and available testing was bogged down with bureaucratic red tape. For example, if we had a patient under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19, initially we could not test them unless they had traveled from mainland China. Later, testing was allowed for anyone in contact with someone from mainland China and then anyone exposed to a known patient with COVID-19. If they did not meet these criteria, despite having symptoms of COVID-19, they could not receive a test.

- We now know that there is significant presymptomatic spread of COVID-19, therefore these policies would have missed many cases in the city.

- When we were able to secure a test, there was initially only one lab that would run the PCR, so the results took days to come back (this improved as more labs opened up in the city and hospitals began running in-house PCRs).

- If patients did not require admission, they were discharged home and told to quarantine until their test results returned. Their discharge diagnosis would usually be documented as upper respiratory tract infection (URI), bronchitis, viral URI not otherwise specified (NOS), or pneumonia. If you only search ED visits with a discharge diagnosis of COVID-19 using the ICD-10 code U07.1, you would miss the majority of the patients who had COVID-19 early in the pandemic but were coded as something else.

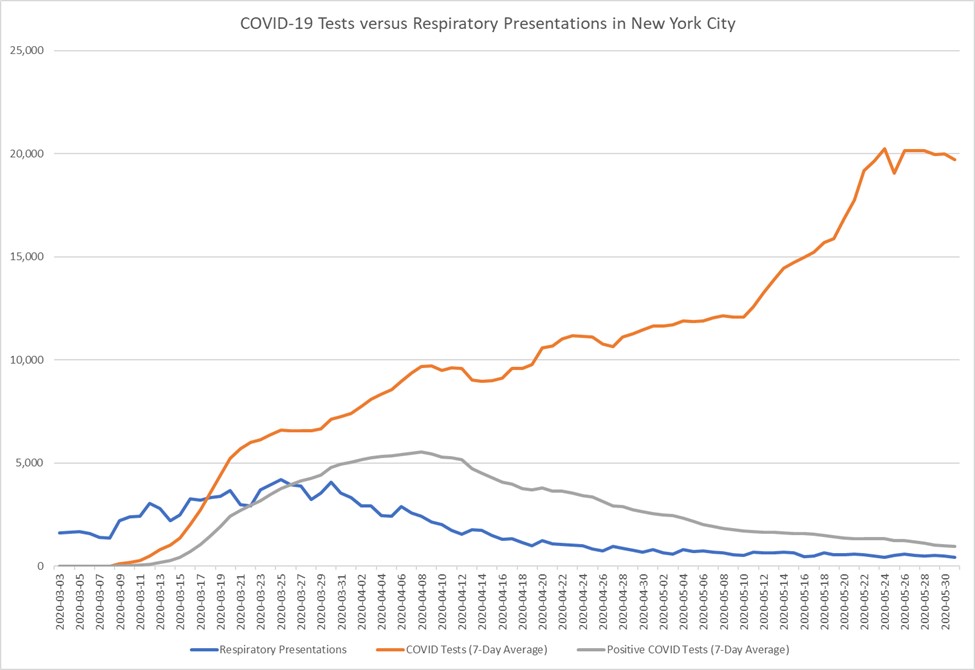

Hockett claims:

But NYC hospitals had tests in March. For example, one week after obstetricians at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center reported a COVID case in an obstetrical patient on March 13, 2020, all women admitted to the labor and delivery unit were being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

This does not prove that tests were widely available in New York City but rather were made available for a high-risk population of patients (pregnant women). This chart demonstrates the number of tests in New York City versus people presenting with respiratory symptoms to the EDs. You can see it was not until March 17th that number of tests reached same the same level as respiratory presentations.

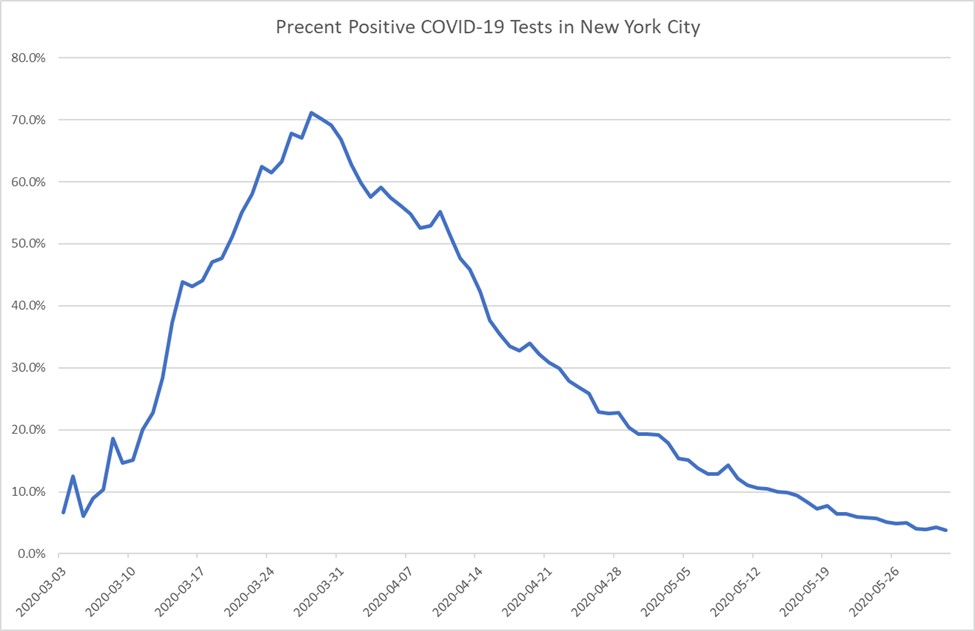

Hockett then discusses the test positivity rate seen in New York City in the spring:

The positivity rate of 50%-75% apparently didn’t raise questions about whether SARS-CoV-2 had been circulating among millions of people after many months. Instead, it led public health & elected officials to see “spread” and call for more testing.

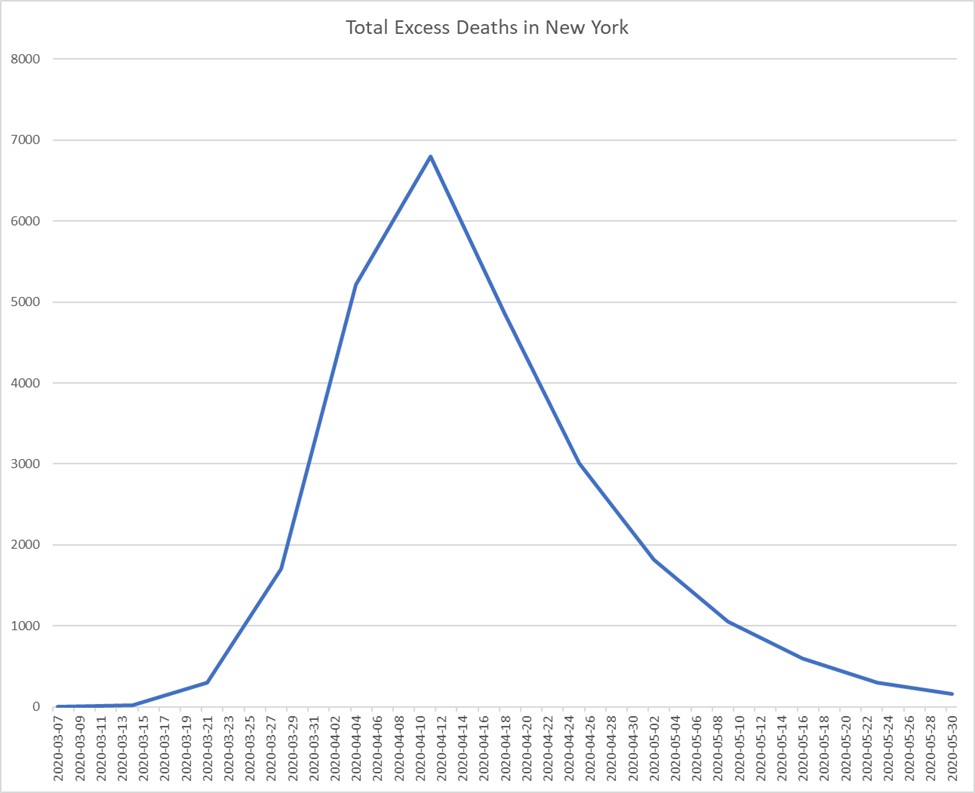

The test positivity rate does not support her assertions, as it shows that we were primarily testing sick COVID patients in the hospital and not patients in the community, given the lack of widespread testing at the time. Look at the spike in the test positivity rate and compare it to New York’s excess mortality. The positivity rate peaks at 71.2% about two weeks before the peak in excess deaths (a lagging indicator of COVID severity). If COVID-19 had been circulating in the community before, why did it take months to see this spike in excess deaths? It appears to be remarkably related to the spike in test positivity, meaning it was related to COVID infections. You cannot just assume that all of these positive cases were just “incidental” when there was a surge of excess deaths that followed.

It is also important to note that there was no ICD-10 for COVID-19 infection at the beginning of the pandemic. This did not become available until April 2020. Basing an analysis on an ICD-10 code unavailable during a portion of the period under study is fatally flawed.

The CDC gave us interim guidance for documenting other ICD-10 codes to use in February 2020, including pneumonia (J12.89, B97.29), acute bronchitis (J20.8, B97.29, J40), lower respiratory infection (J22, B97.29, J98.8), acute respiratory distress syndrome or ARDS (J80, B97.29), and exposure to COVID-19 (Z03.818, Z20.828). Coding was also provided for some symptoms if a definitive diagnosis was not made, such as cough (R05), shortness of breath (R06.02), and fever unspecified (R50.9). Therefore, you can see that relying on data analysis using only the COVID-19 ICD-10 code U07.1 missed large numbers of patients presenting to the ED or admitted with COVID-19. This is the problem with relying on ICD-10 codes for data analysis without understanding the full history of the situation and how it evolved.

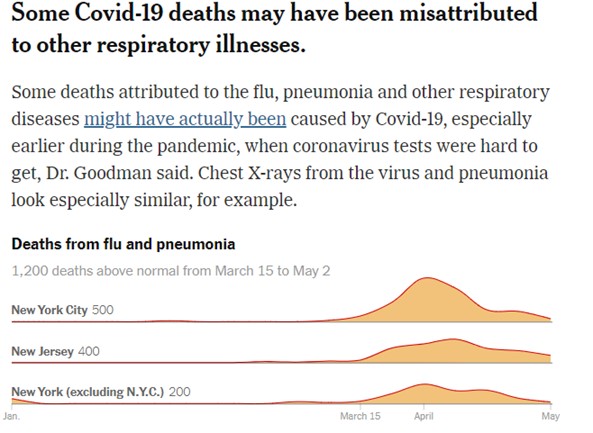

Data presented in The New York Times is consistent with this fact, demonstrating an unseasonable increase in deaths from pneumonia and respiratory illnesses above what would normally be expected during the spring of 2020 (900 excess deaths from respiratory diseases in New York alone). For the reasons outlined above, these were likely COVID-19 deaths that were not categorized as such, given the lack of both sufficient testing capacity and a COVID-specific ICD-10 code. Just ask yourself: did people suddenly start dying in larger numbers from respiratory illnesses out of the blue, or was this increase in deaths because of a novel respiratory virus (SARS-CoV-2) circulating in the community?

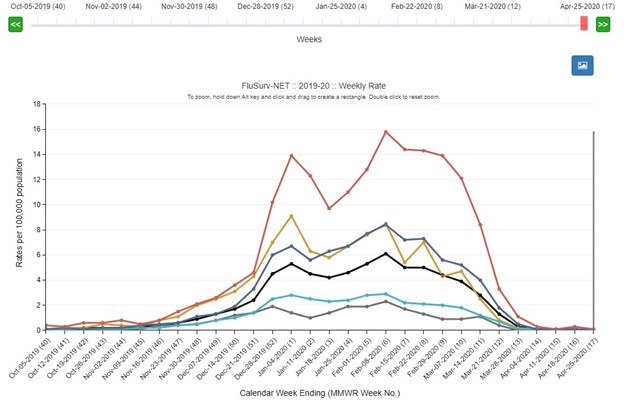

The CDC data shows that hospitalizations from the 2019-2020 influenza season had significantly decreased by mid-March 2020, which would not explain the spike in deaths from respiratory diseases. Widespread influenza testing was available, so influenza patients would not have been reclassified as COVID-19 patients.

Claim three: NYC emergency department spike in respiratory presentations may have been “panic-driven”

Hockett claims:

Respiratory visits for the 2019-2020 peaked in January, and were on the way down. New York Governor Cuomo issued a lockdown directive on March 10, 2020, and calls to Emergency Medical Services soared, as did the number of people going to emergency rooms with respiratory symptoms.

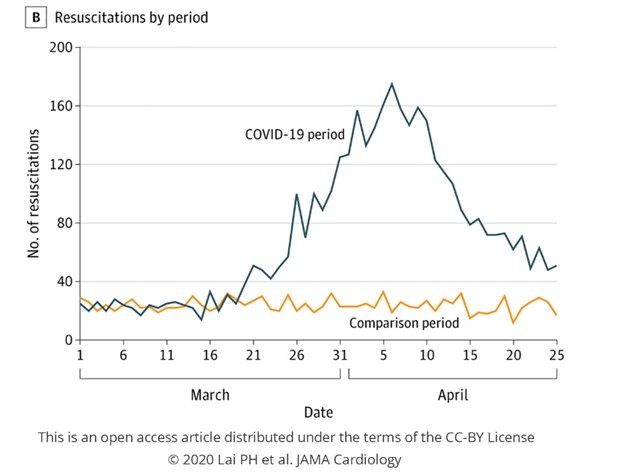

Her image accurately demonstrates a spike in emergency department visits with respiratory symptoms. The peak she referred to in January and February corresponds to the peak in the CDC influenza hospitalization data presented above and was much lower than the March 2020 spike. Visits for respiratory illnesses increased again in March because COVID-19 cases increased, caused by the new respiratory virus that hit the city. She suggests that people were contacting Emergency Medical Services (EMS) out of panic. This does not make sense in light of the excess deaths from respiratory diseases presented above. There have also been studies looking at the increase in home cardiac arrests during the spring of 2020 in NYC, which demonstrated a three-fold increase in at-home cardiac arrests when comparing March/April 2020 to the same period in 2019.

What was the difference between spring 2019 and 2020? Did people become more ill over that year, increasing their risk of at home cardiac arrest? Or was there a novel respiratory virus causing severe illness? I am unaware of any type of panic that could lead to a three-fold increase in at home cardiac arrests. However, respiratory failure from viral pneumonia can cause cardiac arrest. Now, she might claim that people avoided the ED out of fear and were just dying at home from their chronic medical conditions. But which is it? Are people panicking and rushing to the emergency department at the first sign of a cough, or are they staying home and dying because they are afraid to present to the ED? The data from the CDC MMWR also showed that ED visits for cardiac arrests and ventricular arrhythmias increased during the pandemic, which is consistent with patients presenting with a severe illness and not “panic”.

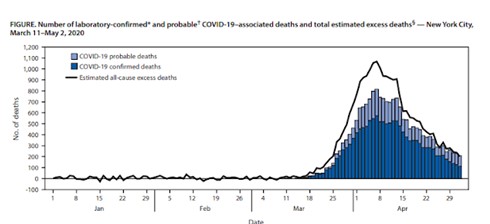

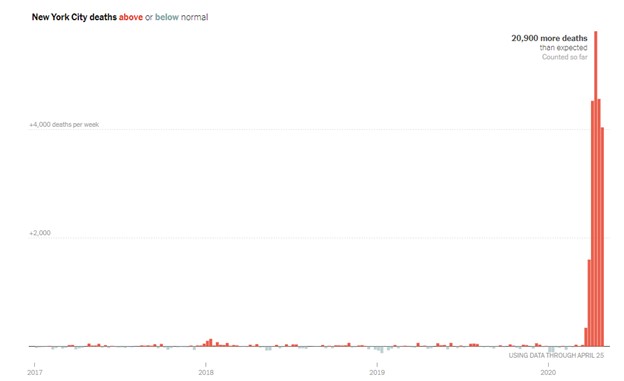

Furthermore, CDC data from New York shows an increase in all-cause excess death starting near the end of March 2020. I am unaware of any physiological change that would result in people with “psychogenic illness” dying in excess numbers. She has also claimed that people may have been admitted “with COVID”, but I am not sure how that would account for the excess deaths. Excess mortality data do not rely on PCR testing or the clinical diagnosis of COVID-19, or other reasons Hockett may give to dismiss the data. It is purely people who died in larger numbers than normal in March and April 2020, which contradicts her claim that “SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating among millions of people for many months”. If it was circulating for many months, where did the excess deaths come from?

Hockett goes on to claim:

But most emergency room visitors with respiratory symptoms were not diagnosed with COVID. Huh. To me, it appears the dramatic rise and fall was triggered by fear rather than “spread.”

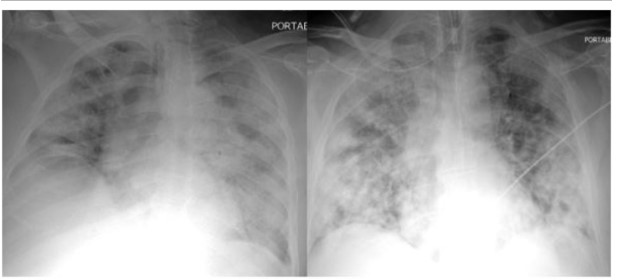

Again, this shows a lack of understanding of all the above points. Patients with respiratory symptoms had COVID-19, but due to the lack of testing and appropriate diagnostic codes, they were not labeled as such. If she audited the medical records of these patients (and not just billing codes), she would see that they had respiratory symptoms and x-rays consistent with COVID-19. Below is a typical chest x-ray of a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. I do not think you need a doctor to confirm that this person was not just presenting to the ED with “panic”.

We also had to devise strategies to split ventilators between two patients because of shortages. This would only happen in a crisis. We would not need to ration ventilators if the hospitals were just full of the “worried well”.

Claim four: Most people presenting to the emergency room were not admitted to the hospital

Hockett claims:

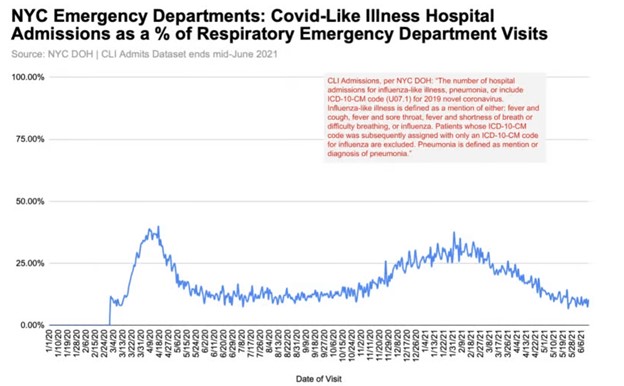

Peak hospital admissions for COVID-like illness (CLI) were 40% of respiratory emergency department visits – another data point that hints at folks rushing to the ER at the first sign of a cough.

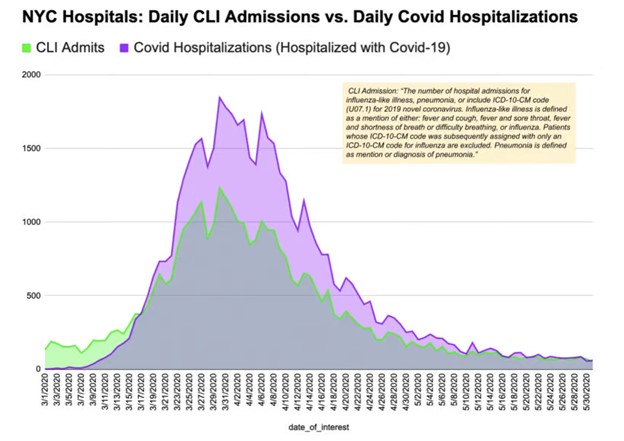

She is falsely assuming that because the majority of respiratory viral-like illnesses were not admitted to the hospital that the hospitals were not overwhelmed, and the patients only had minor concerns. This assumption is incorrect. Relying on diagnostic codes for COVID-19 and COVID-like illness (CLI) does not capture the full scope because (as noted above) many were given diagnostic codes for bronchitis, pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection, and ARDS. COVID-like illness was defined as fever and either cough or shortness of breath. However, many people with late COVID-19 disease do not have a fever. This JAMA study found that only 30.7% of a cohort of patients were febrile at presentation to a hospital in New York in March-April 2020. The other 69.3% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 would not have met the definition of “COVID-like illness”. Thus, her chart below is a gross underestimate of patients admitted with COVID-19, as many did not fit the definition of CLI.

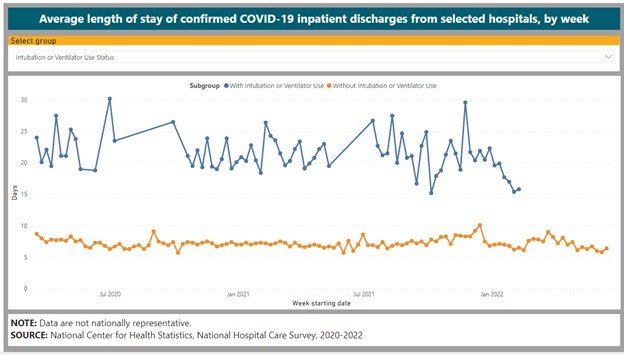

One must take into account many factors when deciding whom to admit to the hospital, including overall bed capacity, occupancy, staffing, and available resources. The patients admitted to the hospital were critically ill, required a tremendous amount of care, and were often hospitalized for several weeks. This creates bed shortages and made admitting new patients from the ED more difficult. You can see that the average length of stay for non-ICU/non-intubated patients (no ventilator) was close to 10 days.

Critically ill patients in the ICU had lengths of stay from 3 weeks to over a month. The turnaround time from admission to discharge was not quick. This creates a backlog of patients in the hospital. So even if the patient volumes were lower due to fewer patients coming to the ED, a surge of high-acuity patients when the hospital is at capacity would quickly overwhelm the system. The flow of patients from the ED to the hospital is a complex network and involves multiple steps, personnel, and resources. These nuances cannot be appreciated by looking at numbers on a spreadsheet.

We could not have possibly admitted every single patient with COVID-19 to the hospital; there were not enough resources for that. There was a triage process that reserved hospital admission for the sickest COVID-19 patients. New York Presbyterian developed a program that sent borderline COVID-19 patients home with portable oxygen, an oxygen saturation monitor, and twice-daily telehealth monitoring to divert admitting patients to the hospital.

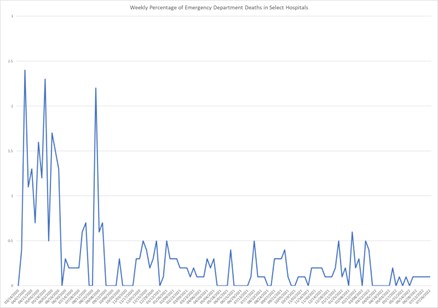

There was an increase in patients dying in the emergency department as well, which would have also contributed to lower numbers of admissions, as per this CDC data:

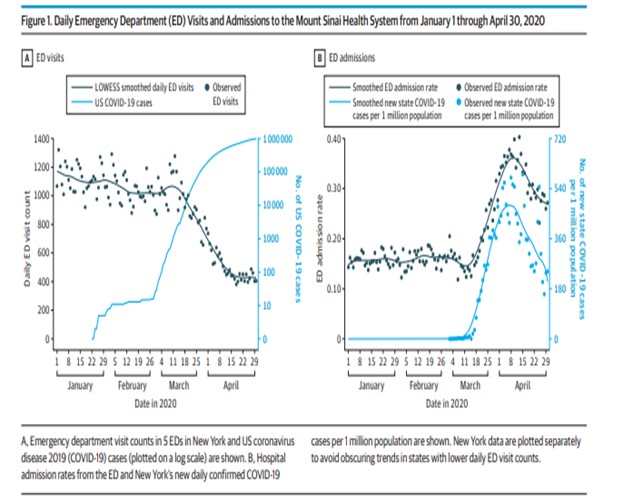

Despite all these measures and decreased total emergency department patients, the admissions rate increased. It was found that despite emergency presentations decreasing by 63.5% in New York hospitals, the admission rate increased by 149%.

Hockett had this to say about the JAMA paper:

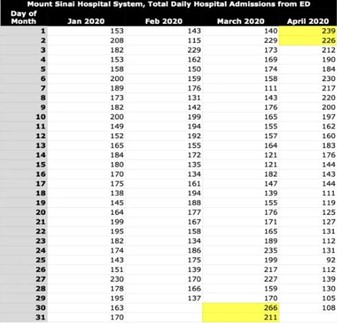

Mount Sinai’s rise in admissions from the ED was short-lived. The rate increase is more dramatic than the raw-number increase due to the ED visit drop. Without historical data, I can’t say whether the 266 admits from the ED on March 30 was unprecedented, or what admission criteria/protocols were being followed.

266 admissions in a day, up from 150 to 200 in the weeks prior, is an incredible increase if you understand how hospital admissions work. These are not just random numbers. They represent critically ill patients who require an incredible amount of care. I cannot stress enough that the length of stay of these patients could exceed three weeks. This puts a huge strain on resources, which is why our hospitals had rapidly expanded our capacity, especially in the ICU. Again, you do not need to be an expert to understand this simple equation: if the number of patients admitted exceeds the number of patients discharged and you have a fixed number of beds, then your system quickly becomes overwhelmed.

She said, “I can’t say whether the 266 admits from the ED was unprecedented or what admission criteria/protocols were being followed”. This could have been easily answered if she had spoken with a physician who worked at one of these hospitals during the pandemic. I have already offered to have this discussion with her but my requests have been rebuffed.

It is important to note that hospitals are not homogenous. They are made up of many different departments, including medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and surgery, to name a few. COVID-19 is a medical disease, so the medical department had to expand its capacity while the others shrank. The entire inpatient structure had to be changed. Why would we need to increase staff on our units, expand bed capacity, convert rooms to negative pressure, and turn operating rooms/coronary angiography labs and post-anesthesia care units into ICUs (all of which cost a ton of money at a time when revenue was low) if we did not see a surge in hospital admissions? We wouldn’t have created the extra capacity just because we wanted more room for activities.

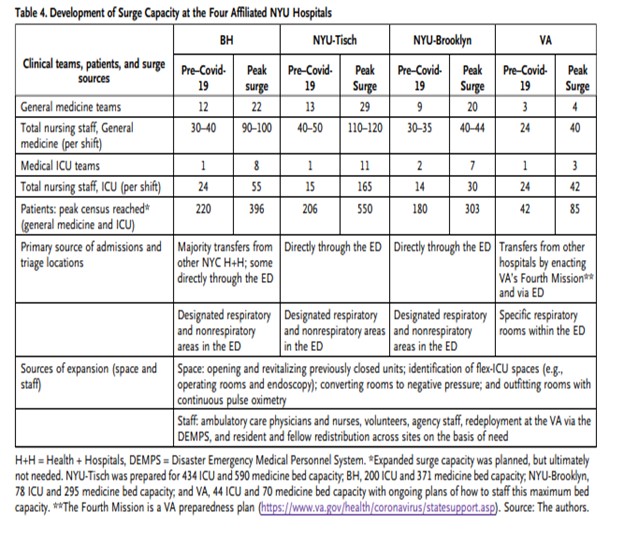

This article outlines the restructuring at New York University Hospitals to accommodate the surge of COVID-19 admissions. Table 4 demonstrates that the medicine/ICU capacity at NYU Tisch increased by a whopping 62% from its pre-COVID baseline.

The primary source of those admissions was the emergency department. ICU-staffed teams increased by 90%, medical-staffed teams by 55%, and ICU nurses by 91%. I again ask Hockett, why did we have to do this if hospitals were not overwhelmed in the spring of 2020? Why did we need to expand general medicine and ICU team capacity? Why did the peak census more than double? Did we do this to accommodate panicked patients who were not really sick? Did we have to do all this to accommodate mass amounts of incidental COVID patients? Or was there a genuine need to do this because a novel respiratory virus devastated our city? You can also review the restructuring that took place at Cornell and Columbia.

In her most recent post “NYC’s Hospital System Never Reached Full Capacity in Spring 2020” Hockett states:

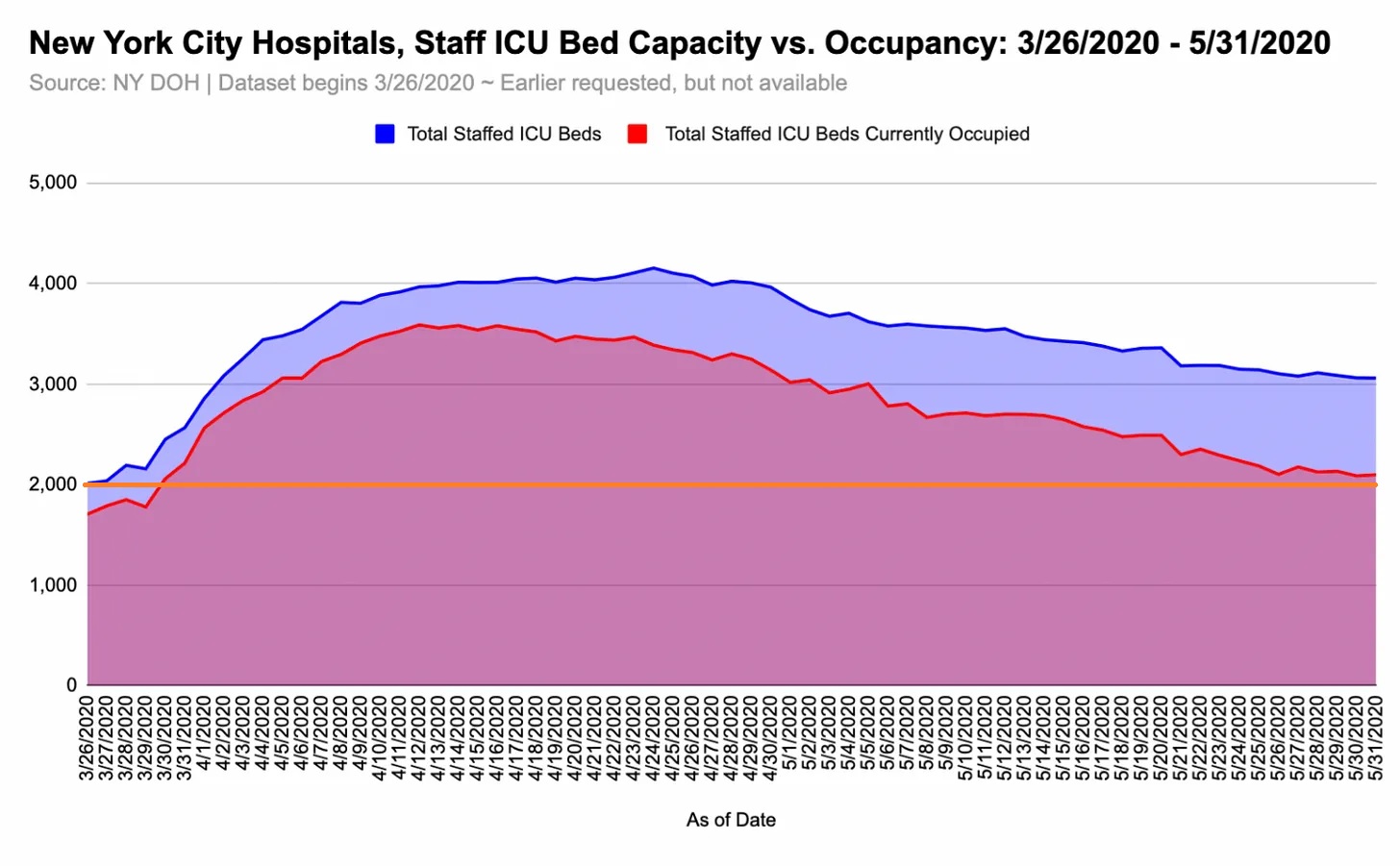

Systemwide, New York City hospitals did not reach full capacity in spring 2020. The city’s staffed acute care and ICU beds were 85% and 90% occupied, respectively, at their late March/early April peaks.

This is yet another example of Hockett not understanding the complexities of hospital capacity in the middle of a global pandemic. Her analysis amounts to bed capacity = X and occupied beds = Y, X > Y, so hospitals were not overwhelmed. As I mentioned earlier, hospitals can become overwhelmed for various reasons.

One thing Hockett forgot to consider in her analysis is that the NYC hospital system is not a monolith. She is assuming that every single hospital in NYC was impacted the exact same way by COVID, so therefore not exceeding the city-wide bed capacity meant that the system was not overwhelmed; but this was not the case. For instance, there are several specialty hospitals in NYC (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Hospital and The Hospital for Special Surgery) that did not see the same influx of COVID patients the other hospitals did. There are many reasons for this, one of which is that many of these hospitals are not associated with emergency departments (most COVID admits were through the ED). The bed capacity for these less-impacted hospitals is also included in Hockett’s dataset. So she used city-wide data on hospital bed capacity but did not realize that the dataset is very heterogeneous and does not accurately reflect the impact COVID had on many hospitals that accepted COVID patients primarily. This could have been avoided if she had analyzed bed and ICU capacity data from individual medical centers throughout the city.

I have added the orange line to her ICU bed capacity figure. You can see that the original ICU capacity of the city was greatly exceeded. The occupied beds above this orange line represent the expanded capacity to accommodate the surge. If these beds had not been expanded, the city-wide ICU capacity clearly would have been exceeded. She’s essentially saying that we weren’t overwhelmed because we didn’t exceed the worst case scenario disaster plan. But hopefully you can see that we had to greatly expand ICU capacity in the city to accommodate the surge in critically ill patients.

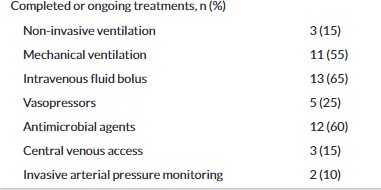

What Hockett fails to include in her analysis is that these are not just random numbers on a spreadsheet. They represent critically ill human beings who required a tremendous amount of care. ICU-level COVID patients were often intubated and mechanically ventilated (hooked up to a breathing machine); they were on several continuous drips of medications which required constant monitoring and titration. These medications were essential to keep the patients sedated and paralyzed while on the ventilator, maintain their blood pressure at an appropriate range, and help their hearts pump blood. COVID had many extra-pulmonary manifestations, which resulted in conditions such as renal failure requiring continuous venovenous hemodialysis (a machine hooked up to a large catheter inserted into the neck that filters the blood when the kidneys no longer work). Intubated patients often needed to be placed in a prone position several times a day. This is when we literally flipped patients from their backs onto their abdomens to help with ventilation. This required a whole team of trained professionals to do it successfully. Other patients were placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machines, which also require highly trained teams to manage. I hope you can appreciate just how complex this situation was.

In her follow-up post, Hockett tries to refute my claim that EDs were filling up with critically ill, ICU-level COVID patients:

There is no data corroborating claims about ICU-level patients being intubated and vented in the EDs. How staff felt in NYC EDs, and why, was not the subject of my November 3 post.

She could have avoided this if she had taken the time to ask someone who worked in the ED during this time. Because ICU beds were full of critically ill patients (many of whom had greater than a 3-week length of stay), the ED began to fill up with ICU-level patients. There was nowhere to admit these patients, so they needed to board in the ED until a bed became available. This highlights the fact that EDs can become overwhelmed for a variety of reasons (one of which being highly complex acutely ill patients boarding in the ED due to lack of hospital capacity).

This study discusses a Philadelphia hospital’s strategy to open an ED-ICU to care for ICU-level patients boarding in the ED. I can tell you that most NYC hospitals had similar ED-ICU setups (you can read about them in the articles outlining the COVID surge protocols at NYU, Columbia, and Cornell above). The data presented shows that 55% of patients in the ED-ICU were intubated and required mechanical ventilation.

Claim five: Many patients counted as COVID hospitalizations in the spring of 2020 were not admitted with COVID-like illness

Hockett states:

Data indicate that approximately 40% of inpatients with a COVID diagnosis (via test, symptoms, or both) from mid-March through April 2020 had not been admitted with COVID-like illness.

She claims that because there was a discrepancy between patients admitted with a COVID diagnosis and COVID-like illnesses, most patients were not admitted with COVID-19. As previously demonstrated, fever, a requirement for CLI, was not universal in COVID-19 patients. She claims these admissions were not COVID-19 because they did not get classified as CLI. I would ask her why she thinks they were admitted (as I’ve already demonstrated, the hospital wards were full, so why would we needlessly admit patients).

NYC hospitals began running out of supplies, including inhaled medications, kits to place central lines in veins, and portable oxygen tanks. Why on earth would we be running out of basic supplies if our hospitals were not full of very sick patients who were admitted through the ED? Incidental COVID patients don’t consume massive amounts of oxygen.

This assumption again relies upon billing codes, which are insufficient when used in isolation, absent of the clinical context of the situation. She could have avoided spreading all of this disinformation by just asking someone who does this for a living.

Under normal circumstances, if a patient came in with a COVID-like illness (fever, cough, shortness of breath, pneumonia) and tested positive for COVID after the note was written, a window for billing would pop up. You would code for COVID and then list the subsequent ICD-10 codes for their other symptoms only if those symptoms didn’t represent a manifestation of the disease itself.

The American Hospital Association provided guidelines on billing during the pandemic:

People infected with COVID-19 may vary from being asymptomatic to having a range of symptoms and severity. Therefore, for coding purposes, signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19 may be coded separately, unless the signs and symptoms are routinely associated with a manifestation. For example, cough would not be coded separately if the patient had pneumonia due to COVID-19, as cough is a symptom of pneumonia

We did not have to code for the three cardinal symptoms of COVID-like illness (cough, fever, shortness of breath) if those symptoms were due to COVID-19. Therefore, the label of “COVID-like illness” would not be applied to these COVID-19 patients.

It is also worth mentioning that billing and coding take time, time that we did not have, as our wards were filling up with sick and dying patients. Ensuring we accurately documented every single symptom for billing purposes took a back seat to ensure our patients stayed alive. Because of this, the NY governor set forth a list of liability waivers to protect healthcare workers during the worst of the surge and one of these waivers provided immunity from record-keeping liability. As a result, we did not have to be as meticulous with our billing and coding. We were not hounded by billing compliance officers during the worst of the surge (mostly because they were nurses and redeployed to the COVID units).

Providing further evidence, as the caseload improved in NYC, the COVID diagnoses matched the CLI diagnoses as the healthcare system became less overburdened and time was available for proper coding/billing.

She then goes on to explain why she thinks the “gap” between COVID-19 and CLI diagnoses occurred:

While the gap between the two sets of numbers could point to nosocomial or attendant-borne spread, it could also simply be the result of incidental positives.

This is complete conjecture on her part. I will refer again to the need to create new ICU space, expand capacity, track and ration ventilator use, and split ventilators. We would not need to do this if people presented with “incidental COVID”. We sent COVID patients home with portable oxygen; we certainly would not be admitting incidental COVID cases just for funsies.

Claim six: The relationship between hospital inpatient deaths with COVID on the death certificate and people who were hospitalized because they had COVID is unclear

Hockett claims:

The gap between CLI admissions and COVID hospitalizations (shown below) started seven days after the stay-[at]-home order. In the weeks that followed, it appears more people were being coded daily as COVID hospitalizations than were being admitted to the hospital with CLI. From March 18th through May 30th, there were ~16,200 more COVID positive hospitalizations than CLI admissions.

In addition to my explanation above for the “gap” between COVID diagnoses and CLI, this statement contradicts her argument that “hospitals were not overwhelmed with patients”. Why were there 15,000 inpatient deaths in NYC if the hospitals were not full of sick and dying patients? Why were there so many deaths if the hospital was just full of “worried well” or asymptomatic incidental COVID patients? Excess death data from New York shows there were almost 21,000 excess deaths in the spring of 2020, for which she has no alternate explanation if COVID-19 was not the cause.

She goes on to say:

Over 15,000 NYC hospital inpatient deaths in these weeks have COVID on the death certificate, per CDC WONDER. Without [a] detailed record review, there’s no way of knowing how many of the 15K had COVID symptoms when they were admitted

This is consistent with COVID-denialism arguments that patients died “with COVID” instead of it. However, some poor employees at the CDC went through 375,000 death certificates of COVID-19 patients because of these claims. They found that 97% had “a plausible chain-of-event condition (e.g., pneumonia or respiratory failure)” indicating these patients indeed died of symptomatic COVID-19.

Again, she’s making assumptions. If she looked at actual medical records and death certificates, she would see that the patients dying from COVID were actually dying from COVID.

She could also have asked any doctor who had to fill out COVID death certificates during this surge for some collateral information.

She continues her attempt at gaslighting NYC frontline workers with this quote:

It’s no wonder Michael Senger, Ethical Skeptic, and other analysts (including me) have said it was misuse of ventilators, protocol-induced staffing shortages, isolation, failure to treat, similar factors that resulted in thousands of Spring 2020 iatrogenic deaths in New York City and elsewhere.

She blames this surge in deaths not on the disease itself but on the doctors inappropriately treating patients with bad protocols (which was not true). I want to remind the reader that Hockett did not provide care for COVID patients in NYC at the height of the surge and never has. Any critique of the management of these patients on her part is not based on the clinical reality of practicing crisis-level care during a global pandemic.

Ventilators were a scarce resource during the pandemic, and they were reserved for the sickest COVID patients. We do not intubate healthy patients. Intubation is a measure of last resort. There are other, less invasive methods of ventilation that were trialed first: high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and BiPAP. There were also legitimate concerns about aerosolization from HFNC/BiPAP combined with concerns about PPE shortages and limited negative pressure rooms at the beginning of the pandemic which limited their use initially.

But this is where being a clinician who actually treated these patients comes in handy.

If you follow me on Tik Tok (Dr.Eric.B), you know that anyone who wants to play armchair doctor gets the medical question of the day! So, I would ask Hockett (or any skeptic) what she would do in the following situation (this is a very common patient that we saw in the spring of 2020):

A 65-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia presented to the ED in the setting of fever and cough for four days. She tested positive for COVID.

The patient’s vitals on presentation were a heart rate of 110 bpm, a blood pressure of 150/62 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 94% on 6 liters by nasal cannula.

She is admitted to the medicine floor. Over the next day, her oxygen requirement increased, and she was placed on 15 liter non-rebreather mask with a SpO2 of 92%. She is using accessory muscles to breathe. She is somnolent and barely rousable to noxious stimuli. Arterial blood gas (ABG) is 7.30/58/60. She is escalated to BiPAP 15/5 mmHg with 100% FiO2. Chest x-ray (CXR) demonstrates worsening bilateral infiltrates consistent with ARDS. Despite max BiPAP settings, the patient’s SpO2 is 84%, RR 40, HR 135, ABG 7.15/85/50.

Would you intubate this patient? If not, what would be your plan? I’m not doing this to be cheeky or to flex my medical knowledge, but I am doing it to show you just how complex the management decisions were. It’s easy to play Monday morning quarterback when you weren’t the one having to make these life and death decisions in real time.

Let’s not pretend like we intubated every patient who presented to the ED with a cough just because. We reserved intubation for the sickest patients. And if you needed intubation with COVID-19, the likelihood of survival was low because your disease state was far too advanced. This was also at the pandemic’s beginning when we had little-to-no therapies to treat COVID. These management decisions were incredibly complex and made in real time with very little information at our disposal. It’s frustrating that non-clinicians feel emboldened to chime in with their opinions on how these patients should have been treated. .

Hockett ends her most recent post with the pièce de résistance of gaslighting:

I understand that New York City doctors and nurses may find these data challenging to integrate with their ‘lived experiences’ in spring 2020, or may believe that only people who were working in the city’s hospitals at the time – or medical doctors/researchers – should be able to speak to these data.

You don’t have to be a NYC doctor to speak to these data. However, experience, an understanding of the nuances of the emerging situation at the time, and expertise matter, no matter what Hockett would have you believe. This is the same for any profession. I would never presume to critique a pilot’s ability to fly a plane when I have no expertise in that field. We have to stop pretending that everyone’s opinions on this subject are equal. They’re not. The data analysis of a Ph.D. reviewing numbers on an Excel spreadsheet from her living room is not the same as the data analysis of a medical doctor who actually lived through the NYC surge. This isn’t credentialism, it’s the facts.

At the end of the day, her articles amount to a sad attempt at gaslighting, historical revisionism, and disinformation thinly veiled under the guise of “legitimate” data analysis. She sat in the comfort and safety of her living room, hundreds of miles away from New York City, analyzing data she didn’t understand because she lacked the appropriate clinical context. It’s very easy for her to do this when she never once stepped foot inside one of our hospitals, never once had to worry if she had enough PPE to make it through the day, never once had to walk past refrigerated morgue trucks parked in front of the hospital, never once had to make life and death decisions with little information. I have offered Hockett and many of her supporters the opportunity to discuss this live. However, my requests have been flatly rejected. I truly believe that a face-to-face conversation with someone who lived through the surge of 2020 would force her out of her comfort zone and force her to realize that the reality of the situation was in stark contrast to her data analysis. Most importantly, it would force her to realize that she is wrong.

As I said in the beginning, I don’t owe Hockett an explanation or justification. I know what I lived through, what my colleagues lived through. No amount of Hockett’s data analysis can change that. You can call this an appeal to emotion, and I don’t care. You can call this an appeal to authority. I don’t care. I have provided evidence and an explanation of the data, which demonstrate that our hospitals were indeed overwhelmed in the spring of 2020. The proof of this is incontrovertible. I don’t expect this to change her or the rest of her colleagues at the Brownstone Institute’s minds. They are intransigent, and convincing them to face reality and admit they don’t know what they’re talking about would be a Sisyphean effort. Despite this, my offer to have this discussion with Hockett live still stands, I truly believe she could benefit from this conversation.

I’m sorry if my tone came across as a bit pointed at times. I would like you to imagine how awful it would feel to be told that what you experienced never happened. That all the suffering, pain, and horrors from the spring of 2020 were somehow a figment of your imagination. That all the peer-reviewed papers, first-hand accounts, news articles, and morgue trucks full of dead COVID victims were an elaborate lie. That one person who never stepped foot inside a NYC hospital has the audacity to call all NYC healthcare workers liars (and let’s be clear, that’s exactly what Hockett is doing). I won’t sit idly by as she and others try to rewrite history and try to minimize the impact COVID had on my hospital, on my city, and my life. I challenge more healthcare workers from NYC and worldwide to take up the mantle and battle this blatant disinformation. Go out there and share your stories. They are worth telling and worth listening to. Don’t let people like Jessica Hockett diminish the power of your voice.