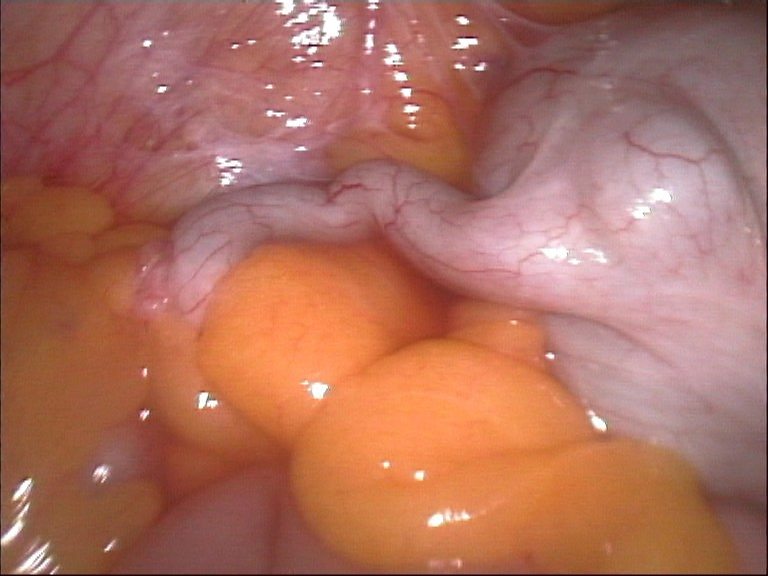

An appendix, mid-appendectomy.

My title doesn’t refer to alternative medicine, it refers to an alternative within medicine: treating appendicitis with antibiotics instead of surgery. You may be surprised to learn that patients with appendicitis don’t always automatically need an appendectomy. A recent randomized controlled trial in Finland compared surgery to medical treatment.

History of appendicitis treatment

There is an excellent, detailed history of appendicitis available online, complete with anecdotes illustrating its importance. The appendix was not mentioned in early anatomical studies, probably because they were done on animals that didn’t have an appendix. The organ was first described in 1521. The existence of appendicitis (called “typhlitis” until 1886) was gradually recognized during the 19th century, and by the end of that century surgical removal of the appendix had become the standard treatment. Walter Reed, the yellow fever researcher for whom the Army hospital was named, died of a ruptured appendix. King Edward VII’s coronation was delayed while he underwent a life-saving appendectomy.

Appendectomy predated antibiotics, and it was believed that appendicitis would invariably progress to perforation. Once antibiotics were available, doctors experimented with treating appendicitis with them instead of with surgery, starting as early as 1956. The published trials had limitations, so the new study was done to try to get a more definitive answer to the question of whether the antibiotic approach was as effective as the surgical approach.

The study

They enrolled 530 patients age 18-60 with uncomplicated acute appendicitis confirmed by CT scan. They originally screened 1,379 patients; 849 of those were excluded because they didn’t meet the inclusion criteria. 337 had complicated appendicitis, 351 had other findings on CT, 18 were outside the prescribed age range, 116 refused to participate, and 27 were rejected for other reasons. Patients were randomly assigned to antibiotics or to surgery using the open operative approach.

In the group assigned to surgery, one patient did not get the surgery because his symptoms resolved before surgery could be performed (demonstrating that spontaneous remission can occur). The other 272 patients assigned to surgery had successful surgery and were cured. In the antibiotic group, 70 of the 256 antibiotic-treated patients (27%) eventually underwent surgery either during the initial hospitalization (15%) or during the 1-year follow-up period. The study failed to show that antibiotic treatment was non-inferior to surgery: their predetermined criteria of non-inferiority was that fewer than 25% of patients treated with antibiotics would later need surgery; in this study, 27% did. They looked at some secondary outcomes: the length of hospital stay during the original hospitalization was shorter in the surgery group but patients in the surgical group took more days of sick leave (19 days vs. 7 days). 55 patients in the antibiotic group had to be re-admitted, accumulating even more hospital days. The overall complication rate was greater in the surgical group (20.5% vs. 2.8%), but the surgical complication rate for the patients in the antibiotic group who eventually needed surgery was lower (7%) than in the surgery group (20.5%).

They concluded that “most” patients (73%) treated with antibiotics did not need later surgery, and those who did had no significant surgical complications.

Criticism of study

A commenter on the PubMed site pointed out that non-inferiority trials to answer this question are not in the best interests of patients. They assume that avoiding appendectomy is an advantage, they allow too large a margin for failures, and they don’t compare the overall benefits of both approaches (they didn’t address the risks and complications of surgery).

Previous research

A 2011 Cochrane review called the evidence for antibiotics “inconclusive” and the quality of studies low to moderate, and concluded that surgery was still the treatment of choice, while antibiotics might be used in specific patients or conditions where surgery is contraindicated.

A meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journalin 2012 looked at complications, efficacy of treatment, length of stay, incidence of complicated appendicitis, and readmissions. It concluded:

Antibiotics are both effective and safe as primary treatment for patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis. Initial antibiotic treatment merits consideration as a primary treatment option for early uncomplicated appendicitis.

In 2014, a systematic review covering 900 patients found fewer immediate complications with antibiotics (18%) than with surgery (25%) but more subsequent failures. After one year of follow-up, only 63% of patients treated with antibiotics were asymptomatic and had had no complications or recurrences.

A more recent meta-analysis published earlier this year found that the antibiotic approach caused harm. The rate of major complications with antibiotics (10.1%) was significantly higher than the rate of major complications with appendectomy (0.8%). They calculated a number needed to harm (NNH) of 10.7, and a risk ratio of 7.71. In other words, one out of every 10.7 patients treated with antibiotics would have complications, and they were 7.71 times more likely to have them than patients treated with surgery.

Other considerations

In the past, diagnosis of appendicitis was problematic. Not every patient had the classic symptoms of right lower quadrant pain and acute tenderness over McBurney’s point. And not every patient with classic symptoms had appendicitis. Historically, the accuracy of diagnosis was only around 80%. A lot of normal appendixes were removed, and that was considered unavoidable: better to remove a few normal ones than miss the ones that would perforate and kill the patient without surgery. Fortunately, modern imaging techniques allow a much more reliable diagnosis today. The accuracy of ultrasound is between 71 and 97%. The accuracy of CT scanning is between 93 and 98%, but it does have disadvantages (cost, radiation exposure, complications from contrast media).

Most of the studies involved open appendectomy. Since 1993, a safer procedure has been available: laparoscopic appendectomy. Its advantages include a smaller incision, less pain, fewer infections, shorter hospital stay, and quicker recovery. Its disadvantages include increased cost and longer operating times. It is not suitable for every patient: there are contraindications such as a perforated appendix or dense adhesions from previous surgeries. It is much more widely available in the US than in other countries.

Surgery solves the problem once and for all, providing peace of mind. Antibiotics can have side effects. Patients who eventually need surgery after antibiotic treatment are exposed to unnecessary worry, suffering, repeat hospitalization, time off work, etc. I’m not a lawyer, but I wonder if patients who had complications following antibiotic treatment might successfully sue their doctors for not following the standard of practice.

Antibiotics may be the better option for some patients, but we don’t yet have any reliable way to identify which patients those are. And it’s clearly not for everyone. In this study, only 530 out of the original 1,379 patients screened were considered eligible for antibiotic treatment.

Alternative medicine alternatives for appendicitis

Here’s what integrative medicine guru Dr. Andrew Weil has to say:

While there is no alternative to surgery as a treatment for appendicitis, you should request an intravenous (IV) drip of high doses of vitamin C during the operation. High levels of vitamin C speed the healing of surgical wounds. If there’s time (since surgery for appendicitis usually is done on an emergency basis, there may not be), make a tape of healing statements to be played while you’re under anesthesia. A study conducted at Beth Israel Hospital in New York showed that patients who heard taped positive affirmations while they were under anesthesia required 50 percent less postoperative medication than a control group. After surgery, you may be able enhance the healing process with healing touch therapy such as Therapeutic Touch and Reiki, two forms of energy medicine.

There are websites that offer home remedies in lieu of treatment by doctors. Among other questionable remedies, drinking a quart of buttermilk a day is recommended to treat chronic appendicitis and consuming small quantities of green gram (mung beans) thrice daily is recommended to treat acute appendicitis.

A naturopath claims to have cured several cases of appendicitis with a regimen of high dose IV vitamin C, constitutional hydrotherapy, thymus extract, and an herbal tincture.

An acupuncture website recommends palpating the appendix point on the lower leg to diagnose appendicitis. It says complications can occur during a surgical operation, but there are no complications of not having one. That’s wrong-headed. The complications of not having surgery include rupture, peritonitis, and death.

What about chiropractic? According to chiropractic theory, appendicitis should not develop if the spine is in proper alignment. On a chiropractic forum, a second-year chiropractic student answered the question “Can chiropractic help appendicitis” by saying “HELL NO!!” but claimed that chiropractors are trained in detecting appendicitis. A chiropractic website has an account of curing appendicitis with prayer.

Homeopathy offers many treatment suggestions. One website says “Every case of appendicitis needs professional evaluation by an experienced homeopathic physician before deciding if it is suitable for surgery or homeopathy.”

Needless to say, none of these alternative treatments have been scientifically tested, and most of them are highly implausible. In my opinion, patients who rely on them instead of treatment by a mainstream doctor are risking their lives.

Was I wrong?

The recent study was brought to my attention by a reader. He remembered a SkepDoc column in Skeptic magazine where I wrote that we didn’t need to do randomized controlled trials to test appendectomy, and he thought this new study proved me wrong. I’m always happy to admit it when I am wrong, because it means I have learned something. But in this case I am not persuaded that I was wrong. My point was that we don’t need to do RCTs for things that are well established like the usefulness of parachutes when jumping out of airplanes. The efficacy of appendectomy for appendicitis is well established, and the new study did not question it. In fact, they used appendectomies as the gold standard fallback when antibiotics failed. The study did not question whether appendectomy worked; it was only asking if antibiotics might also work and if surgery might be avoided in some cases. By analogy, there is no need to do an RCT asking if parachutes work, but there might be a reason to do an RCT someday if someone invents a contraption, perhaps with some kind of wings and high-tech bubblewrap, that might offer equal or better protection.

Conclusion: A valid choice that must be made by patients

I think most people would want the most effective treatment for a potentially fatal disease, and if they chose a less effective treatment they would need to have a very good reason to do so. The Cochrane review found that the effectiveness of surgery was 97.4%, antibiotics 73.4%. If I had appendicitis, I would choose surgery because I would want to be sure the problem had been dealt with and would not recur. But the evidence shows that antibiotic treatment is a valid alternative for patients who are unable or unwilling to have surgery.