One of the most common narratives I observe coming from those promoting “alternative medicine” (i.e., quackery) is that we are “losing the war on cancer”. (Just Google the phrase if you don’t believe me, and it’s not just alternative medicine mavens who are repeating the meme.) Usually, these sorts of stories come up during anniversaries of President Nixon’s declaration of “war on cancer” (particularly decade anniversaries like the 40th anniversary in December 2011, leaving us less than two years away from the next big round of stories). Of course, I’ve always objected to the use of the metaphor of “war” for progress against the disease and even more so how this particular metaphor lumps a large group of very different diseases into one term, “cancer”, as though it were all one disease. Even so, it is a useful exercise from time to time to determine how science-based medicine is doing against the large group of diseases known collectively as “cancer” and, in particular, how it is doing against the most common cancers that afflict humanity. Fortunately, the American Cancer Society (ACS) does just that every year in January, when it publishes its yearly update to its cancer statistics, thus providing a snapshot of where we are in terms of cancer.

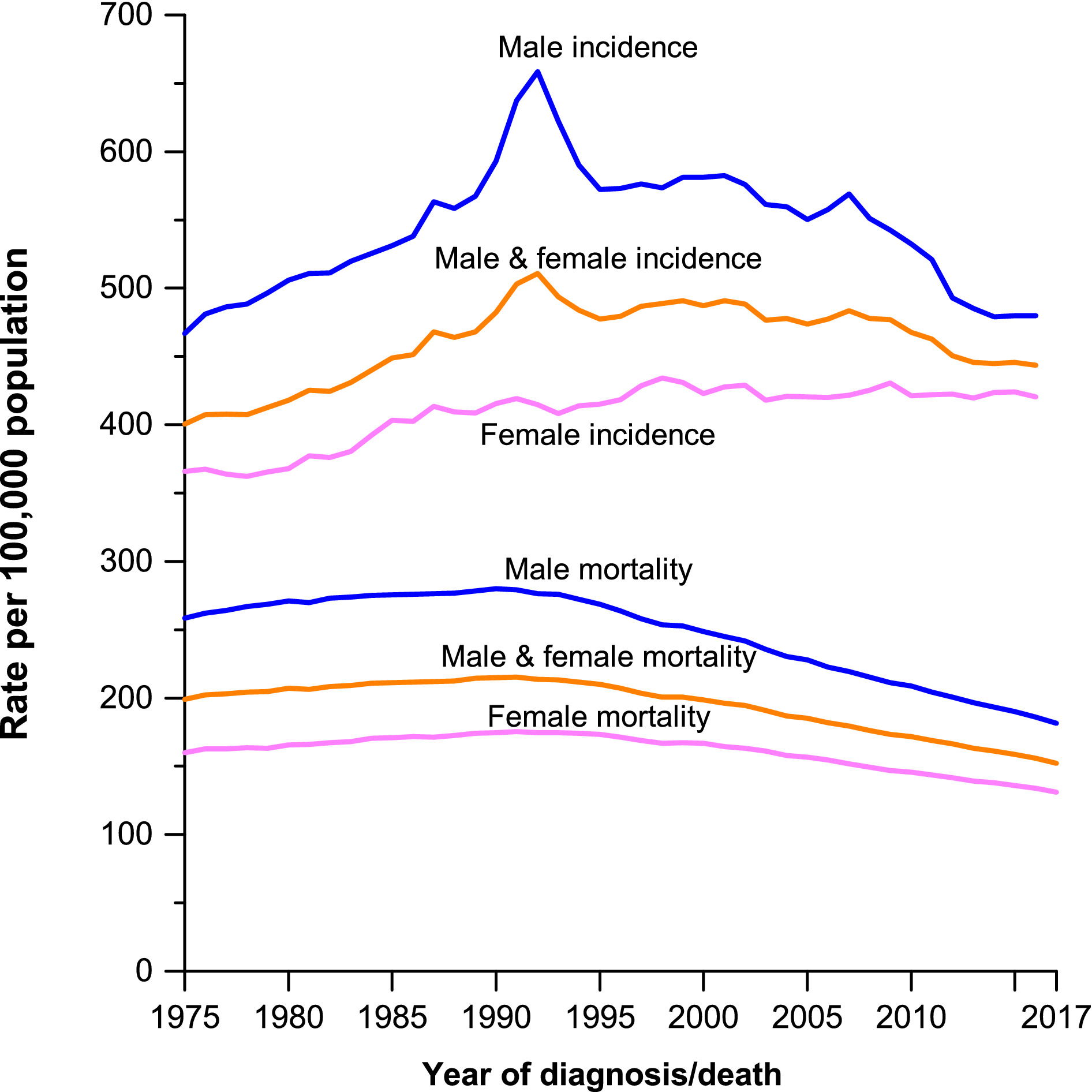

Where we are is actually not bad. This year, the ACS reported the single largest one-year decline in cancer mortality and the continuation of 25 years of continuous decline in death rates due to cancer:

The death rate from cancer in the US declined by 29% from 1991 to 2017, including a 2.2% drop from 2016 to 2017, the largest single-year drop ever recorded, according to annual statistics reporting from the American Cancer Society. The decline in deaths from lung cancer drove the record drop. Deaths fell from about 3% per year from 2008 – 2013 to 5% from 2013 – 2017 in men and from 2% to almost 4% in women. However, lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer death.

The decline in the death rate over the past 26 years has been steady. Overall cancer death rates dropped by an average of 1.5% per year between 2008 and 2017. This translates to more than 2.9 million deaths avoided since 1991, when rates were at their highest. A total of 1,806,590 new cancer cases and 606,520 deaths are expected in the US in 2020, which is about 4,950 new cases and more than 1,600 deaths each day.

The numbers are reported in “Cancer Statistics, 2020,” published in the American Cancer Society’s peer-reviewed journal CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

Again, cancer is not all one disease; so it’s necessary to unpack these figures and go into more detail. The news is mostly, but not all, good. I also realize that, to those who have lost loved ones to cancer or who are facing imminent death from cancer, these figures might well represent cold comfort. Cancer does, after all, still remain the number two cause of death in the US, close behind heart disease, at least for now. (Cancer is expected to surpass heart disease as the number one cause of death soon and has already done so in some countries.) That means, for all the progress that’s been made in terms of declining cancer mortality, a lot of people—far too many—still die of a form of cancer and that that will continue for the foreseeable future.

The good news and bad news

Whenever discussing cancer statistics, I like to use a few key figures from the yearly ACS report on cancer statistics. First, there’s this one, which shows the estimated numbers of new cases and cancer deaths for cancers in males and females:

As you can see, lung cancer remains by far the biggest cancer killer for both men and women, and the vast majority of lung cancer cases are attributable to smoking tobacco. In terms of incidence, gender-specific cancers (prostate in men and breast in women) are the most common, and each is the second most common cause of death. Pancreatic cancer is a particularly deadly cancer, making up only 3% of cancers but 8% of cancer deaths.

Here are the highlights of the positive findings:

- Lung cancer death rates declined by 51% from 1990 to 2017 among men and 26% from 2002 to 2017 among women. From 2013 to 2017, the rates of new lung cancer cases dropped by 5% per year in men and 4% per year in women. The differences reflect historical patterns in tobacco use, where women began smoking in large numbers many years later than men and were slower to quit. However, smoking patterns do not appear to explain the higher lung cancer rates being reported in women compared with men born around the 1960s.

- Breast cancer death rates declined 40% from 1989 to 2017 among women.

- Prostate cancer death rates declined 52% from 1993 to 2017 among men.

- Colorectal cancer death rates declined 53% from 1980 to 2017 among men and by 57% from 1969 to 2017 among women.

These are amazing numbers and reflect real progress. Yes, declines in smoking are enough to drive a fraction of the decline in the overall death rate from cancer, but tobacco use alone doesn’t explain the striking declines in mortality from breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer.

Personally, I always find it interesting, from a historical perspective, to examine the incidence curves that are always included by the ACS every year, first for cancer overall:

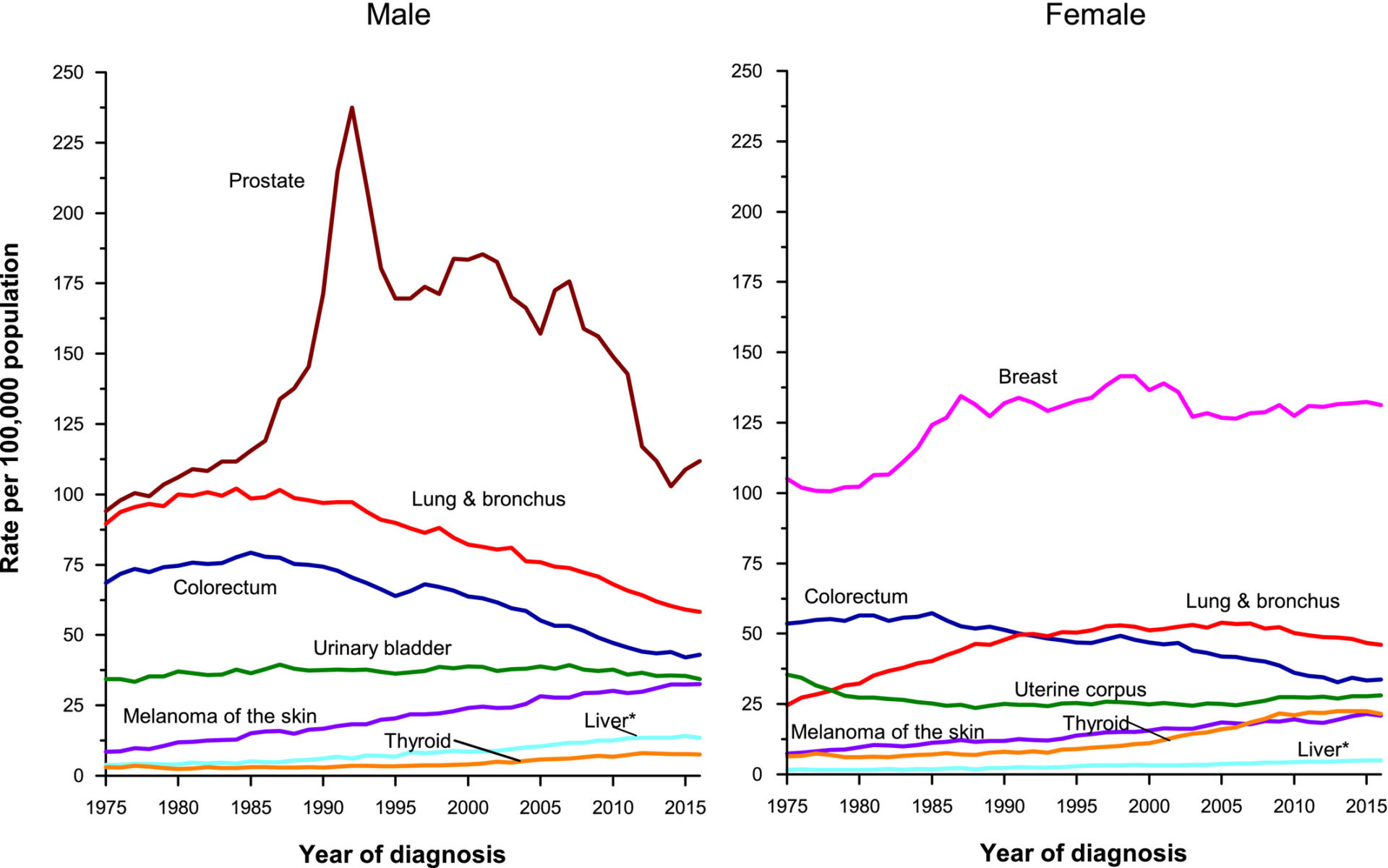

And individual cancers in men and women:

As you can see, although cancer incidence has been declining rapidly in men and the slow increase in women has mostly leveled off. People who see these curves for the first time often ask about the spike in cancer incidence for men in the early 1990s. That increase was driven by widespread prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) testing among previously unscreened men and the subsequent overdiagnosis of a lot of asymptomatic prostate cancer that likely didn’t need treatment. The overall decline in cancer rates for men between 2007 and 2014 was driven primarily by the decline in lung cancer incidence due to a decrease in the number of people smoking, but the decline leveled off after that. The authors attribute that leveling off to slowing declines for colorectal cancer (CRC) and stabilizing rates for prostate cancer. The overall incidence of cancer in females has remained fairly stable for the last quarter century or so. The authors note that the decline in lung cancer rates has “been offset by a tapering decline for CRC and increasing or stable rates for other common cancers”.

In terms of incidence, there are some interesting observations, some of which are likely due to the increasing prevalence of obesity, which is a strong risk factor for some cancers. For instance, breast cancer incidence has increased by 0.3% per year since 2004, and the authors suggest that this increase could well be due to increasing obesity and declines in the fertility rate. Some of the first things they teach you about breast cancer in medical school are its risk factors, which include nulliparity (having no children, and actually, having more children correlates with a lower risk of breast cancer, as does breast feeding), early age at menarche (first menstrual period), and late menopause. Obesity, unsurprisingly, is also a risk factor for breast cancer. Of course, the gradual rise in breast cancer rates makes the dramatic decline in mortality from breast cancer (40% in 30 years) even more remarkable.

In addition:

The slight rise in breast cancer incidence rates (by approximately 0.3% per year) since 2004 has been attributed at least in part to continued declines in the fertility rate as well as increased obesity,36 factors that may also contribute to the continued increase in incidence for uterine corpus cancer (1.3% per year from 2007‐2016).37 However, a recent study indicated that the rise in uterine cancer is driven by nonendometrioid subtypes, which are less strongly associated with obesity than endometrioid carcinoma.38 Thyroid cancer incidence has stabilized after the implementation of more conservative diagnostic practices in response to the sharp uptick in the diagnosis of largely indolent tumors in recent decades.39, 40

I’ve written about overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer, thanks to ultrasound screening, and how that has led to consideration of reclassifying an indolent variant of thyroid cancer as not cancerous. The increase in incidence of uterine cancer is a bit of an oddity, and more research will be needed to determine what might be causing it.

And there’s more:

Incidence also continues to increase for cancers of the kidney, pancreas, liver, and oral cavity and pharynx (among non‐Hispanic whites) and melanoma of the skin, although melanoma has begun to decline in recent birth cohorts.28, 44 Liver cancer is increasing most rapidly, by 2% to 3% annually during 2007 through 2016, although the pace has slowed from previous years.8 The majority of these cases (71%) are potentially preventable because most liver cancer risk factors are modifiable (eg, obesity, excess alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and hepatitis B and C viruses).45 Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, the most common chronic blood‐borne infection in the United States, confers the largest relative risk and accounts for 1 in 4 cases.46 Although well‐tolerated antiviral therapies achieve cure rates of >90% and could potentially avert much of the future burden of HCV‐associated disease,47 most infected individuals are undiagnosed, and thus untreated. Only 14% of the more than 76 million individuals born during 1945 through 1965 (baby boomers) had received the recommended one‐time HCV test in 2015.48 Compounding the challenge is a greater than 3‐fold spike in acute HCV infections reported to the CDC between 2010 and 2017 as a consequence of the opioid epidemic, of which 75% to 85% of cases will progress to chronic infection.49

We’ve also noted the increase in liver cancer incidence before. Sadly, it looks as though the opioid addiction epidemic will in future decades claim more victims due to liver cancer.

Contrary to what you might read, there doesn’t seem to be a signal indicating increased cancer incidence due to an as yet undiscovered environmental exposure or toxin. Cancers for which obesity is a risk actor are, unsurprisingly, on the rise, and cancers for which tobacco is a major risk factor are on the decline, while cancers associated with hepatitis B and C infections are on the rise. As Steve Novella has said many times, the best advice for minimizing your chances of being diagnosed with cancer are don’t smoke, exercise, eat a healthy diet, maintain a healthy weight, get your colonoscopy (which actually has decreased the incidence of colorectal cancer), and use sunscreen. Also, be vaccinated against hepatitis B to prevent liver cancer and against HPV to prevent cervical and other HPV-associated cancers and screened for hepatitis C if you’re in the appropriate age range.

Declining cancer mortality

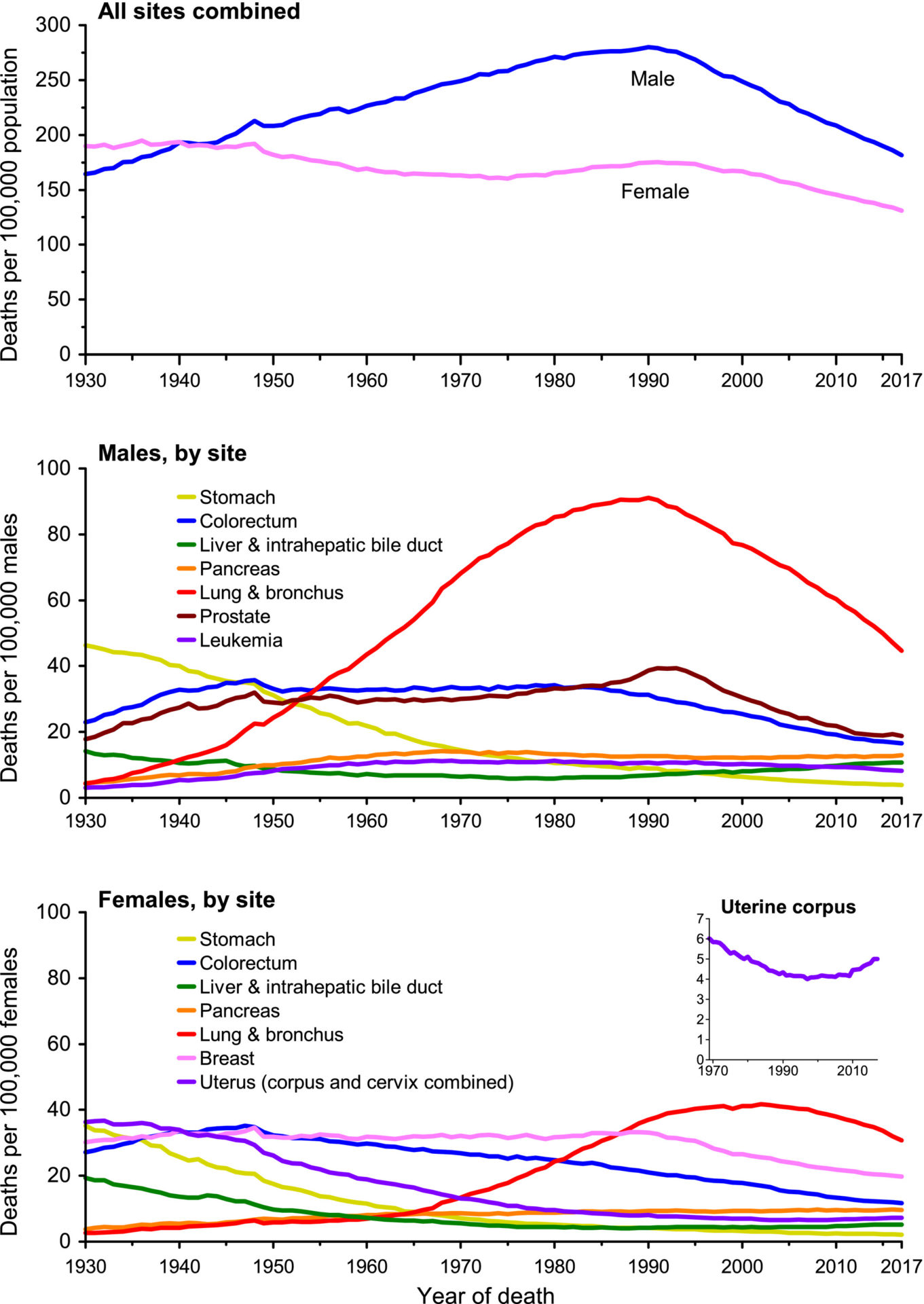

There’s one more figure that I like to show from this yearly report, and that’s a more detailed breakdown of cancer mortality going all the way back to 1930:

As you can see, cancer mortality for men climbed continuously from 1930 and peaked around 1990. Unsurprisingly, that increasing mortality was mostly driven by smoking, as the generation of men with the highest usage of tobacco reached the age and number of years spent smoking when lung cancer is most likely to strike. Mortality began to decline, delayed by a number of years of course, as smoking rates began to decline after 1972.

Getting into the weeds a bit:

The progress against cancer reflects large declines in mortality for the 4 major cancers (lung, breast, prostate, and colorectum) (Fig. 7). Specifically, as of 2017, the death rate has dropped from its peak for lung cancer by 51% among males (since 1990) and by 26% among females (since 2002); for female breast cancer by 40% (since 1989); for prostate cancer by 52% (since 1993); and for CRC by 53% among males (since 1980) and by 57% among females (since 1969). The CRC death rate in women was declining prior to 1969, but that is the first year for which data exclusive of the small intestine are available. Two decades of steep (4% per year on average) declines for prostate cancer are attributed to an earlier stage at diagnosis through PSA testing, as well as advances in treatments.61, 62 However, prostate cancer death rates stabilized in recent years (Table 5), possibly related to declines in PSA testing and an uptick in the diagnosis of distant stage disease.32 Declines in mortality have also slowed for female breast and CRC. In contrast, declines in lung cancer mortality have accelerated, from approximately 3% annually during 2008 through 2013 to 5% during 2013 through 2017 in men and from 2% to almost 4% in women.

In other words, a lot of progress has been made, but, again, lung cancer is primarily driving the bus here, along with the other most common cancers. Some of this progress is from screening. Some of it comes from better treatments. In particular, there is one success story based on improved treatment, namely melanoma, for which the mortality decline has been truly dramatic:

Recent mortality declines are even more rapid for melanoma of the skin, most likely reflecting improved survival in the wake of promising new treatments for metastatic disease. In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved ipilimumab, the first immune checkpoint inhibitor approved for cancer therapy,63 and vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, for the treatment of advanced melanoma.64 Subsequently, the 1‐year relative survival rate for metastatic melanoma escalated from 42% for patients diagnosed during 2008 through 2010 to 55% for those diagnosed during 2013 through 2015.65 Likewise, the overall melanoma mortality rate dropped by 7% annually during 2013 through 2017 in men and women aged 20 to 64 years compared with declines during 2006 through 2010 of approximately 1% annually among individuals aged 50 to 64 years and 2% to 3% among those aged 20 to 49 years (Fig. 8). The impact was even more striking for individuals aged 65 years and older, among whom rates were increasing prior to 2013 but are now declining by 5% to 6% per year.

Yes, melanoma is a nasty one. Traditionally, when I was in training, there was basically little or no systemic therapy. There was interferon, but that didn’t improve survival much, and it had a number of side effects that made patients feel terrible while they were using it. Other than surgical advances, mainly in the form of less radical surgery such as sentinel lymph node sampling supplanting radical lymphadenectomy (removal of all the lymph nodes in a nodal basin), there just wasn’t much else to offer melanoma patients. Given that melanoma responded, albeit weakly, to immunotherapy with interferon, it’s not entirely unexpected that it would respond even better to the new generation of immunotherapy agents, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Unfortunately, not all the news is good. Mortality rates have risen over the last decade for pancreatic cancer in males and uterine cancer in females, as well as for some less common cancers, such as cancers of the liver, small intestine, anus, penis, brain and nervous system, eye and orbit, and oral cavity and throat. Increases in liver cancer mortality are, however, slowing in women and stabilizing in men

Also, there are large disparities in cancer mortality and incidence, and the largest disparities exist for cancers that are, theoretically at least, the most preventable, such as lung cancer, cervical cancer, and melanoma of the skin. For example, lung cancer mortality and incidence rates are three- to -fourfold higher in Kentucky than they are in Utah, and that’s all based on smoking prevalence.

For cervical cancer:

Similarly, cervical cancer incidence and mortality currently vary by 2‐fold to 3‐fold between states, with incidence rates ranging from <5 per 100,000 population in Vermont and New Hampshire to 10 per 100,000 population in Arkansas (Table 10). Ironically, advances in cancer control often exacerbate disparities, and state gaps for cervical and other HPV‐associated cancers may widen in the wake of unequal uptake of the HPV vaccine, which has already shown efficacy in reducing the burden of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grade 2 or higher.81 In 2018, up‐to‐date HPV vaccination among adolescents (those aged 13‐17 years) ranged from 38% in Kansas and Mississippi to >70% in North Dakota and Rhode Island among girls and from 27% in Mississippi to >70% in Massachusetts and Rhode Island among boys.75

Basically, states that make it a priority to vaccinate against HPV will likely ultimately benefit through decreased incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer.

There are also disparities in cancer survival between African-Americans and whites, with the five year survival for all cancers combined being 67% overall, 68% for whites, and 62% for African-Americans. After adjusting for age, sex, and stage at diagnosis, the relative risk of death after a cancer diagnosis is 33% higher in black patients than in white patients, and this disparity is even larger for American Indians/Alaska Natives, among whom the risk of cancer death is 51% higher than it is for whites.

Finally, the incidence of childhood cancers has been slowly increasing by about 0.7% per year since 1975 for reasons that have not been worked out. However, death rates from childhood cancers continue to decline. The overall mortality from childhood cancer declined from 6.3 (per 100,000 population) in children and 7.1 in adolescents in 1970 to 2.0 and 2.7, respectively, in 2017, for overall cancer mortality reductions of 68% in children and 63% in adolescents. During that same time period, mortality from leukemia has declined by 83% in children and by 68% in adolescents; from lymphoma by 80% and 82%, respectively. The five year relative survival rate has improved from 58% for all cancers combined in the 1970s to 84% in the early 2010s for children.

We are not losing the war on cancer

Critics of oncology and some quacks, not infrequently argue that we’re “losing the war on cancer.” (Again, just Google the phrase “losing the war on cancer”.) Arguably, we’re slowly winning, at least if you insist on using that metaphor. Mortality from cancer is declining, and for some cancers the decline has been quite dramatic just within my lifetime. For breast cancer, it’s been incredibly dramatic within my professional lifetime. I graduated from medical school over 30 years ago, and in that time mortality from breast cancer has declined by 40%. That is, quite simply, incredible to me.

Of course, it’s a painfully simplistic question, as is another question I keep hearing, “Why haven’t we cured cancer yet?” (Mainly because it’s complicated as hell.) What the evidence has shown clearly (and based on the ACS report is continuing to show) is that overall death rates from cancer are steadily falling, driven by declines in death rates from most of the common cancers. Meanwhile, five year survival rates are climbing for most cancers, even for more advanced disease.

Of course, as tobacco-caused cancers decline, unfortunately the incidence of cancers linked to obesity is climbing. So is the incidence of liver cancer, which is linked to hepatitis B and C, which are in turn increasingly linked to the opioid addiction epidemic. It will be decades before we know the full effect on cancer incidence and mortality of the obesity and opioid epidemics, and it is possible that some of the progress made thus far in reducing cancer mortality will be reversed. We also have a long way to go in terms of making sure that race and socioeconomic status do not impact one’s risk of dying from cancer.

Still, even if you insist on using the metaphor of a war, I would argue that, contrary to the common perception, we are not losing the “war on cancer”. Mortality is declining and survival is increasing for most cancers. It’s just that progress is slow, and results are mixed. I’ve always thought that it was hubris to think that progress would be anything other than slow against such a deadly, complex, multifactorial set of diseases that go under the label of cancer. Conquering all cancers is a project that will take more than decades. It will take generations. I also understand that the dramatic progress made is cold comfort to those who’ve lost loved ones to cancer or who are facing imminent death themselves from cancer. After all, I lost my mother-in-law to breast cancer 11 years ago, and by then the decline in breast cancer mortality since my youth had already reached dramatic levels.

Even if you think that progress against cancer has been too slow, the latest ACS data demonstrate conclusively that the narrative regular SBM readers hear from various proponents of “alternative cancer cures”, that cancer is killing more than ever, that big pharma doesn’t want to cure cancer, is not only incorrect but detached from reality.